Chapter 17. Reflections on working with south Sudanese refugees in settlement and capacity building in regional Australia

Andrina Mitchell

• acculturation

• intercultural awareness

• the barriers to engagement

• professional self-care and burnout.

Roles

The occupational therapist was employed by local government in two separate roles. Firstly, she acted as a case manager for newly arrived refugee entrants for the first 6 months after arrival. Through this federally funded programme, entrants arrived under the Special Humanitarian Program, meaning that the refugee entrants had been sponsored by Sudanese family or friends already settled in Australia. Generally, the new arrivals lived with their sponsor for the first 3–6 months to adjust and to pay back the debts incurred in the immigration process.

Settlement issues and living skills were addressed jointly by the Special Humanitarian Program sponsors and case manager. Typically, sponsors saw it as their responsibility to orientate the new arrivals to Australian culture; however, this created some problems as their level of understanding was not always as comprehensive as they believed it to be. Areas of priority in this role included access to services (health, education, children’s services and financial assistance), securing housing, the provision of a culturally appropriate household goods package and undertaking relevant life skills training (tenancy, budgeting, public transport, etc.). Secondly, through state government funding, the occupational therapist was employed as a community consultant as part of a pilot project which sought to build the capacity of emerging refugee communities. The outcomes of this position were to:

• enhance refugee community self-determination and governance skills through mentoring/training

• develop the leadership capacity of women and youth

• become financially self-sustaining through engaging mentors to support them in applying for/managing grants and setting up community enterprises.

In addition to these tasks, roles also involved:

• instigating and facilitating monthly case coordination meetings with the relevant key service providers. Issues around privacy, confidentiality and informed consent with clients had to be resolved. These meetings were essential for peer support, identifying and addressing gaps in service delivery, and allowing for strategic future planning with joint funding applications

• developing, implementing and supervising a volunteer training programme

• advocating for the refugee community at a local level, for example with real estate agents, who went from reluctant participants to eventually become champions of the programme

• assisting the Sudanese community to advocate for themselves and to become cultural consultants around programme development, particularly in relation to children’s services and legal issues

• lobbying, in conjunction with service providers and the Sudanese community, for changes to the current funding arrangements around service provision.

The refugee community and the local community

The local south Sudanese refugee community was diverse, made up of about 90 to 95 individuals, with more than half of them less than 12 years old. The ethnic mix was made up of five main tribes (Azande, Chollo, Nuer, Nuba and Dinka), with a roughly equal mix of Christians and Muslims. Originally, 11 Sudanese families chose to relocate from the state’s capital city to this regional town of 30 000 people. All had been in Australia for 2–3 years, spoke functional English, had car licences and were ready for work. Of the original families, eight remained after 18 months. They, in turn, sponsored another 11 families, couples and individuals. Developing language proficiency was the main focus of this group’s initial settlement period.

In addition to the core Sudanese community, there were also about 10 to 20 transient members, mostly youth, who worked at the local abattoir when they could and then disappeared back to the city for months on end. These individuals were harder to engage with, as they were relatively disconnected from the larger Sudanese community, generally ignoring the elders and demonstrating their own set of values, beliefs and behaviours. Their occasional antisocial behaviour was strongly disapproved of by the Sudanese community as it went against their cultural norms and was particularly detrimental to their reputation.

It should be noted that the host township was extraordinarily homogeneous as a group before the Sudanese arrived, with 97% coming from a Christian, English or Irish background – 1% Aboriginal, 2% European and Asian backgrounds (Department of Sustainability and Environment 2001).

Acculturation

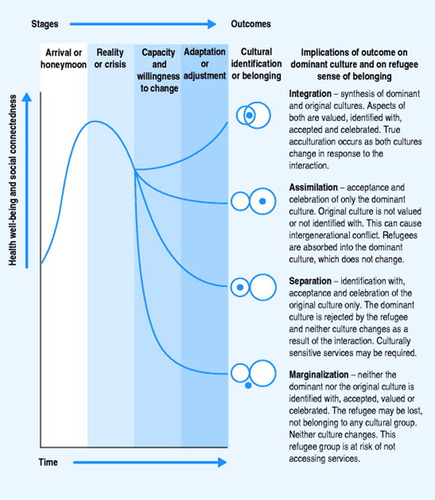

Acculturation is a predictable settlement process that migrants and refugees move through where contact is made, cultural values are compared and the new culture is totally or partially accepted or rejected (Fig. 17.1). In true acculturation, both cultures are changed as a result of the interaction.

|

| Figure 17.1 Source: adapted from Berry et al 1986, as cited in Culhane 2004. |

In regard to refugee health, better outcomes are seen in those who become integrated or assimilated into the new culture (Plavsic 2002). Turner (2003) reinforces the importance of acknowledging this process by stating that ‘the question of utmost importance to the healthworker here is “where is the client in the acculturation continuum/journey?”’. Typically, the new arrival will pass from initial optimism and hope to a crisis, often brought on through difficulties with language, finances or not understanding the new culture. At this point, depending upon their capacity and willingness to change or adapt, the refugee will take one of four paths, becoming integrated, assimilated, separated or marginalized (Berry 1998, cited in Culhane 2004).

Factors that influence these divergent paths include:

• the level of choice in the migration process

• ease of language acquisition

• feelings of belongingness

• cultural similarities and understanding

• occupational opportunities

• prior experiences of torture and trauma

• openness to change

• experiences of acceptance or discrimination in the new culture.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree