Reduction and Stabilization of the Distal Radioulnar Joint following Galeazzi Fractures

Benjamin S. Zellner

John R. Dawson

Lee M. Reichel

DEFINITION

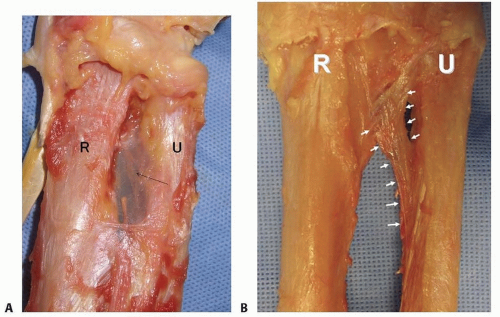

Fracture of the radial shaft with an associated distal radioulnar joint (DRUJ) dislocation (FIG 1A,B)

It is well established that anatomic stabilization of the radial shaft fracture typically results in a stable DRUJ that can be treated nonoperatively with a period of immobilization.

When the DRUJ is either irreducible or unstable, following anatomic reduction and compression plating of the radius fracture, operative stabilization of the DRUJ is required.

Pediatric injury is not discussed in this chapter.

ANATOMY

DRUJ

Stability to the DRUJ is conferred through the bony articulation between the sigmoid notch of the radius and the ulnar head, ligamentous attachments, and muscular stabilizers.5

The radius of curvature of the ulnar head is smaller than the sigmoid notch, resulting in a loosely constrained bony articulation. This allows both rotational and translational movements between the radius and ulna with pronosupination. In addition, this loose bony articulation must depend on soft tissue components to be the primary joint stabilizers.5

Triangular fibrocartilage complex (TFCC)

The dorsal and volar radioulnar ligaments of the TFCC are considered the primary stabilizers of the DRUJ.18

The deep fibers of the radioulnar ligaments attached at the fovea are located at the base of the ulnar styloid.

For this reason, in the less common instance when an ulnar styloid base fracture accompanies a Galeazzi fracturedislocation, fixation of ulnar styloid fracture may restore DRUJ stability.

Distal interosseous membrane (DIOM) and distal oblique bundle (DOB)

The DIOM lies deep to the pronator quadratus and connects the radius and ulna (FIG 2A).

Biomechanical studies demonstrate that the distal membranous portion of the interosseous membrane functions as a secondary stabilizer of the DRUJ.14, 20

When present, the DOB originates at the distal ulna and inserts at the inferior rim of the sigmoid notch of the radius blending with the capsular tissue of the DRUJ.18 Cadaveric studies report the DOB is present in 40% of specimens (FIG 2B).15

Moritomo14 has hypothesized that in Galeazzi fracturedislocations, when there is loosening but not rupture of the DOB, instability can be managed by anatomic reduction of the radius.

Radius reduction and the subsequent retensioning of the DOB restore stability even when a TFCC injury is present. Persistent DRUJ instability after radial fracture restoration may be the result of DOB disruption.14

Radius

The majority of Galeazzi fracture-dislocations occurs in distal third of the radius but can occur anywhere along the radius.12

Greater than 50% of radial shaft fractures less than 7.5 cm from the distal radial articular surface are associated with injury to the DRUJ compared to 6% of more proximal radial shaft fractures.17

PATHOGENESIS

Mechanism of injury

Axial loading of an outstretched arm with forceful hyperpronation of the forearm. Direct trauma to the dorsal radial forearm has also been reported.12

More common in higher energy injuries with a high incidence of associated injuries (30% to 50%)13

The radius fractures and shortens. This shortening results in tearing of the TFCC from its foveal attachment (or an ulnar styloid base fracture with TFCC remaining attached) and subsequent dislocation of the DRUJ.

Galeazzi and irreducible DRUJ (following radius fixation)

Galeazzi and unstable DRUJ (following radius fixation)

It is established that a TFCC (Palmar 1B) injury (or ulnar styloid base fracture with the TFCC attached) occurs in a Galeazzi fracture-dislocation.17 TFCC injury, in addition to DIOM and DOB injury (as described earlier), likely results in continued, significant instability after radius fixation.

NATURAL HISTORY

Galeazzi fracture-dislocations account for approximately 6% of all closed forearm fractures in adults with a male predominance.13

Nonoperative management results in an apex dorsal radius malunion with a dorsally prominent ulnar head. Limitations in pronation, supination, wrist flexion, and wrist extension are common. Pain occurs at the ulnar side of the wrist over the prominent ulnar head.

In contrast, early operative management typically results in excellent or satisfactory results following anatomic reduction and stabilization of radius fracture and DRUJ.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

A high percentage of associated injuries occur, and lifethreatening injuries should be assessed first.

Patients report severe forearm and wrist pain. Deformity is typically present with a prominent ulnar head.

Open injuries of the radius and ulna can occur, and close evaluation of the skin should be performed.

Neurovascular injuries and compartment syndrome have not been widely reported with a Galeazzi injury but should be assessed for completeness and documented even when “negative.” Therefore, all splints, dressings, and clothing need to be removed for proper inspection and palpation and neurovascular examination.

Examination of the DRUJ of the noninjured contralateral extremity is helpful prior to surgical management of the Galeazzi injury to understand the patient’s native DRUJ laxity, especially at the limits of pronation and supination.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Anteroposterior and lateral radiographs of the wrist, forearm, and elbow suffice for diagnosing Galeazzi fracturedislocations.

At presentation, radiographs typically demonstrate the following:

Shortening of the radius on the anteroposterior view with a widened DRUJ

Apex medial angulation of the distal radial segment (toward the ulna)

An apex dorsal angulation of the radius on the lateral radiograph with a dorsal dislocation of the DRUJ

An ulnar styloid base fracture may also be present.

DRUJ subluxation is notoriously difficult to identify.

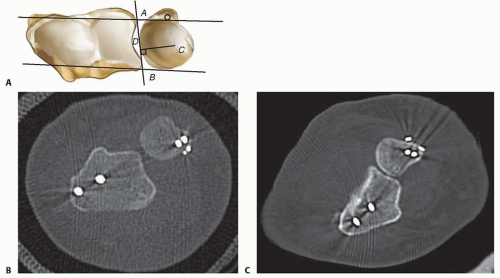

Postoperatively, if there is any concern whether the DRUJ is reduced, computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) should be obtained.

The DRUJ is well visualized in the axial plane to determine subluxation or dislocation.

Multiple methods have been devised to identify and quantify DRUJ subluxation using CT (Mino’s criteria, congruency method, epicenter method, and radioulnar ratio).11 Unfortunately, no reference standard exists (FIG 3A-C).

Despite the advantages of advanced imaging, it is not typically necessary at presentation as soft tissue injury is implied based on radiographic findings in a Galeazzi injury pattern.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Isolated radial shaft fracture

Radial head or neck fracture with DRUJ injury (Essex-Lopresti lesion)

Distal radius fracture with DRUJ injury

Ulnar-sided carpal or ligamentous injuries

NONOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

No role exists for nonoperative care of a Galeazzi injury in a patient who is medically able to have surgery. Hughston’s7 classic series demonstrated that 35 of 38 patients treated without surgery resulted in failure.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Galeazzi fracture-dislocations need to be treated expeditiously. Delay in treatment more than 10 days may negatively impact final range of motion of the forearm.13

The need for operative stabilization of the DRUJ can only be determined intraoperatively after the radius fracture has been stabilized, and the DRUJ is examined for instability.

Preoperative Planning

Preoperatively, the surgeon decides the surgical approach and method of fixation of the radius fracture. It is presumed that at a minimum, the TFCC is injured and the DRUJ will be evaluated intraoperatively.

Decision making and technique regarding approach and fixation of the radius has been described in detail in the chapter entitled Open Reduction Internal Fixation of Diaphyseal Forearm Fractures.

Examination under anesthesia of the uninjured wrist is performed.

Depending on intraoperative findings, the surgeon must be prepared to pin the radius to the ulna, explore the dorsal DRUJ, and possibly repair the TFCC using either open or an arthroscopic technique.

Evaluation of DRUJ instability following radial fixation

The decision to proceed with operative stabilization of the DRUJ for residual instability following radius fixation is not straightforward. Unfortunately, there is no reference standard for evaluating DRUJ stability.

DRUJ instability should always be evaluated after radius stabilization.

Classically, the elbow is flexed to 90 degrees, and the ulna is stressed both volarly and dorsally in supination, neutral, and pronation while laxity, subluxation, or dislocation is assessed. Any laxity less than full dislocation is difficult to quantify even when measured against the examination of the uninjured wrist.

Giannoulis and Sotereanos4 suggested that instability is confirmed following fixation of the radius if the ulnar head can be translated dorsally out of the sigmoid notch (with the forearm fully supinated).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree