Rectus Femoris Transfer

Jon R. Davids

DEFINITION

The gait pattern of children with cerebral palsy (CP) is frequently disrupted by dynamic overactivity of the rectus femoris muscle.

This disruption is characterized by delayed and diminished peak knee flexion in swing phase.

Surgical transfer of the rectus femoris muscle to the medial hamstrings is usually performed in conjunction with other surgical procedures selected to address all elements of soft tissue and skeletal dysfunction that compromise gait in children with CP.

This surgical strategy, termed single-event multilevel surgery (SEMLS), requires a comprehensive assessment of gait dysfunction using quantitative gait analysis.

Proper management (surgical, orthotic, and rehabilitative) in childhood can result in an improved gait pattern that will be sustainable in the adult years.

ANATOMY

The rectus femoris muscle is a portion of the quadriceps muscle group, which also includes the vastus lateralis, the vastus medialis, and the vastus intermedius muscles.

The rectus femoris muscle is the only one of the quadriceps muscle group that is considered to be biarticular, as it crosses both the hip joint and knee joint. The remaining three muscles cross only the knee joint.

The rectus femoris muscle is innervated by the femoral nerve. It has its origin on the anterior inferior iliac spine (direct head) and the innominate portion of the pelvis just proximal to the superior margin of the acetabulum (reflected head) and its insertion on the superior pole of the patella.

The rectus femoris muscle fuses with the underlying vastus intermedius muscle several centimeters proximal to the superior pole of the patella.

The rectus femoris muscle and the other three portions of the quadriceps muscle group envelop the patella to form the patellar tendon, which inserts on the tibial tubercle apophysis of the proximal tibia. It serves as a hip flexor and knee extensor.

In normal gait, the rectus femoris muscle is active in the stance to swing phase transition, where it acts to control the magnitude of the flexion excursion of the knee as the gait velocity increases.13 It is also active at the end of the swing phase to properly position the knee in the transition from swing to stance phase.13

The remaining three portions of the quadriceps muscle group are active during the loading response of stance phase, where they are essential in providing shock absorption function about the knee as the limb is loaded.13

From a functional perspective, the quadriceps muscle group is actually two groups, the first consisting of the rectus femoris muscle and the second consisting of the triceps femoris muscles (remaining three muscles).9

PATHOGENESIS

CP is the consequence of an injury to the immature brain that may occur before, during, or shortly after birth. The nature and location of the injury to the central nervous system (CNS) determines the components of the neuromuscular and cognitive impairments.

Common functional deficits are related to spasticity, impaired motor control, and disrupted balance and body position senses.

Although the injury to the CNS is not progressive, the clinical manifestations of CP change over time owing to growth and development of the musculoskeletal system.

The muscles typically exhibit a purely dynamic dysfunction during the first 6 years of life, characterized by a normal resting length and an exaggerated response to an applied load or stretch.

With time, between 6 and 10 years of age, the muscles develop a fixed or myostatic shortening, resulting in a permanent contracture.

As such, it is best to consider CP not as a single specific disease process but rather a clinical condition with multiple possible etiologies.18

NATURAL HISTORY

Ambulatory children with CP whose gait is disrupted by overactivity of the rectus femoris muscle typically walk with delayed and diminished knee flexion in swing phase. This may be associated with decreased velocity of hip flexion in the stance to swing phase transition and increased ankle plantarflexion in swing phase, called a stiff gait pattern.15, 19

These dynamic gait deviations at the hip, knee, and ankle disrupt the normal limb segment coordination that contributes to functional shortening of the limb during the swing phase of the gait cycle.17 As a result, children with CP who have a stiff gait pattern will exhibit compromised clearance of the limb in swing phase.15, 19

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

The clinical history, as provided by the child and the parents, usually contains complaints of toe dragging, tripping, abnormal shoe wear about the toes, and inability to keep up with peers in play and sports.

A thorough examination will include the prone rectus femoris test (also known as the Duncan-Ely test) (FIG 1).

A positive slow rectus test indicates fixed shortening of the rectus femoris muscle.

A positive fast rectus test indicates the presence of spasticity of the rectus femoris muscle.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Radiographic imaging is not required when determining the need for transfer of the rectus femoris muscle to improve gait in children with CP.

Relevant data from quantitative gait analysis include temporospatial parameters, sagittal plane kinematics at the knee and hip, and dynamic electromyography (EMG) of the rectus femoris muscle.

Gait velocity should be greater than 60% of age-matched normal.3 Children with CP who ambulate with a greatly diminished gait velocity will also exhibit disrupted sagittal plane knee kinematics in swing phase, which will not be corrected by a rectus femoris muscle transfer.

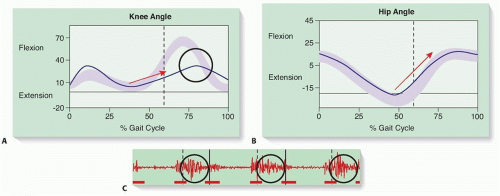

Sagittal plane knee kinematics will show decreased flexion range and velocity in the stance to swing transition, delayed and diminished peak knee flexion in swing phase, and diminished dynamic range of motion with a rounded or mounded wave form in swing phase (FIG 2A).3, 11, 12

Sagittal plane hip kinematics during the stance to swing phase transition should be evaluated when considering surgical transfer of the rectus femoris muscle (FIG 2B).

A poor transition at the hip is characterized by decreased flexion range and velocity and is a contraindication to rectus femoris muscle transfer.3

Poor hip flexor function in the stance to swing transition will result in delayed and diminished peak knee flexion in swing phase, which will not be corrected by a rectus femoris muscle transfer.

Dynamic EMG of the rectus femoris muscle will show prolonged, inappropriate activity into the middle subphase of swing phase (FIG 2C).3, 11, 12

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree