Gastrocnemius Recession or Tendo-Achilles Lengthening for Equinus Deformity in the Diabetic Foot?

Abstract

Contracture of the Achilles-gastrocnemius-soleus complex leading to ankle equinus has been linked to the development of various foot disorders. Decrease in ankle dorsiflexion results in an increase in plantar pressures and in diabetes and neuropathy, increased pressures can lead to ulceration and possibly the formation of Charcot foot. Surgical management of the equinus deformity corrects this abnormality and has the potential to avert the development of Charcot foot or ankle. Gastrocnemius recession, tendo-Achilles lengthening, and Achilles tenotomy have all been offered as surgical solutions to this condition. This article reviews ankle equinus and compares the treatment options available. A video of Hoke’s triple hemisection has been included with this article and can be viewed at www.podiatric.theclinics.com.

Keywords

• Diabetes mellitus • Equinus • Achilles • Gastrocnemius recession • Tendo-Achilles lengthening • Limited joint mobility syndrome

video of open evaluation of Hoke’s triple hemisection accompanies this article at www.podiatric.theclinics.com/.

Introduction

Ankle equinus is a pathologic limitation of ankle joint range of motion caused by a contracted Achilles-gastrocnemius-soleus complex. Researchers have disagreed about the minimum range of motion at the ankle joint required for normal ambulation; however, most agree that at least 10° of dorsiflexion at the ankle is required for normal ambulation. Limited range of motion at the ankle joint is a significant causative factor in the development of abnormal foot function. Ankle equinus (<10° of dorsiflexion) may be the primary pathologic factor in conditions such as clubfoot or neuromuscular diseases or may serve as a causative factor of a disorder that presents in the foot, such as hallux abductovalgus, adult and pediatric flatfoot, Achilles tendinopathy, plantar fasciitis, diabetic foot ulceration, and Charcot neuroarthropathy.1–3 Ankle equinus may also occur after certain partial foot amputations and may become a causative factor in recurrent ulcerations after certain foot amputations. Treatment of equinus varies and depends on the cause, severity, medical comorbidities, and surgeon preference. Currently, there is no gold standard for the treatment of equinus and some controversy exists as to which method is preferred. This article reviews the basics of equinus and compares the most commonly performed procedures, gastrocnemius recession, tendo-Achilles lengthening (TAL), and Achilles tenotomy.

Ankle equinus and the diabetic foot

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimated in 2010 that 25.8 million Americans are affected by diabetes4 and another 79 million are affected by prediabetes. The diabetes epidemic in the United States continues to tax the health care system. It is estimated that up to 25% of people with diabetes mellitus suffer an ulceration within their lifetimes.5 Therefore, identifying potentially modifiable risk factors for ulceration is key to amputation prevention. One such modifiable risk that may contribute to the formation of ulceration is increased plantar forefoot pressures. Veves and colleagues6 found that a plantar ulcer occurred in 35% of diabetic patients with high plantar foot pressures, but occurred in none with normal pressures. Increased plantar pressure has been shown to occur early in the onset of diabetes. Boulton and colleagues7 showed abnormalities in foot pressure occurring early with sensory neuropathy, and this may precede clinical abnormalities. The most important risk factor in the pathogenesis of diabetic foot ulceration is the loss of sensory awareness, which occurs in 60% to 70% of those with diabetes, and therefore high plantar pressure alone is not the cause of ulceration, but rather a casual effect. Frykberg and colleagues8 found that persons with diabetes have a higher prevalence of ankle equinus as compared to non diabetic persons (37.2% vs 15.3%). The researchers also uncovered a significant association between equines and ulceration.8

There are many contributing factors that may lead to increased plantar foot pressures. Some are obvious deformities (ie, bunions and hammertoes); however, a potentially major contributing factor that is often not recognized is limited joint mobility syndrome (LJMS).9 This syndrome is a wide spectrum of disorders and includes reduced range of motion and tissue elasticity, and muscular imbalance. Ankle equinus is part of this spectrum.

Equinus as a source of high plantar foot pressures

The reported overall prevalence of equinus in the diabetic population is 10.3%, however, recently Frykberg and colleagues,8 reported a prevalence of 37.2% in persons with diabetes. Using electron microscopy, Grant and colleagues10 found structural changes in the Achilles tendons of patients with diabetes, characterized by increased density of collagen fibrils, decreased fibrillar diameter, abnormal fibril morphology, and frequent foci of collagenous fiber disorganization. These fine morphologic changes may be the result of nonenzymatic glycosylation, which, as a result, stiffens the Achilles tendon. As the Achilles loses its flexibility, the foot loses its ability to adequately dorsiflex during gait, creating a longer lever arm and placing abnormal forces on the midfoot.11 Decreased ankle dorsiflexion results in shifts in distribution of plantar pressures with peak pressures increased under the forefoot.11

Patients with equinus have significantly higher peak plantar pressures than those without the deformity and are at nearly 3 times greater risk for presenting with increased plantar pressures.12 Simulated Achilles tendon contracture increases the severity of arch depression and forefoot abduction.13 Caselli and colleagues14 showed an increase in forefoot-to-rearfoot pressure with increasing degrees of neuropathy. This finding lends further evidence for the concept that equinus is a progressive deformity and becomes more severe in the later stages of peripheral neuropathy, thereby playing an important role in the cause of diabetic foot ulceration.

LJMS involves more than just an equinus deformity. Orendruff and colleagues15 showed that the relationship between equinus and peak forefoot pressure was significant but, by itself, has only a limited role in causing high forefoot pressure. The soft tissue imbalance that occurs in LJMS is also a major factor in increasing plantar pressures. Abboud and colleagues16 found abnormalities in the tibialis anterior muscle function during the gait cycle in subjects with diabetic peripheral neuropathy. This condition resulted in a prolonged flattening of the foot and a significant increase in plantar pressures.16 Therefore, understanding the relationship and balancing of the dorsiflexory and plantarflexory muscle groups is important when addressing increased plantar pressure.

Procedure selection

When considering surgical correction of equinus, several factors must be considered during procedure selection. Distinguishing which portion of the triceps surae complex is contracted may assist in determining which procedure will be most effective. Traditionally, the Silfverskiold test (the amount of dorsiflexion is evaluated with the knee straight and bent) has been used as a major decision maker in surgical planning, but this assumption may be flawed. Schweinberger and Roukis17 suggested that there is no clinically significant difference between an isolated gastrocnemius equinus and a gastrocnemius-soleus equinus because the timing of passive ankle joint dorsiflexion in the gait cycle only occurs with the knee in an extended position until the heel comes off the ground during toe-off. Aronow and colleagues18 performed a mechanical loading study using 10 fresh frozen cadaveric legs that were loaded with 35.8 kg (79 lb) of plantar force through the isolated gastrocnemius, isolated soleus, or combined gastrocnemius-soleus muscles and found similar redistribution of plantar force from the rearfoot to the midfoot and forefoot in each of the 3 muscle sets tested.

Kay and colleagues19 performed a retrospective review of 54 ambulatory children with fixed ankle equinus treated with either TAL or gastrocnemius recession. Their study garnered information for procedure selection to help improve future outcomes. The gait laboratory was used to identify patients who would benefit from a procedure to correct ankle equinus; however, procedure selection was not made from this information. Procedure selection was based on static examination of dorsiflexion at the ankle with the knee flexed. The gastrocnemius recession was performed in patients who could dorsiflex to neutral and beyond, whereas the TAL was reserved for patients who were unable to achieve dorsiflexion to neutral. Using this test to determine procedure selection produced an end result with no significant difference in postoperative dorsiflexion, whereas after surgery there was significance.

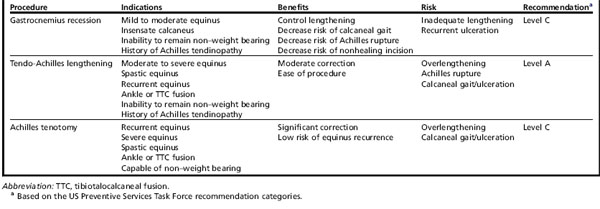

Several factors should be considered when selecting the proper surgical procedure. Three surgical options exist, including gastrocnemius recession, TAL, and Achilles tenotomy. Each option carries its own risks and benefits, and performing the appropriate procedure enhances the outcome (Table 1).

Gastrocnemius recession

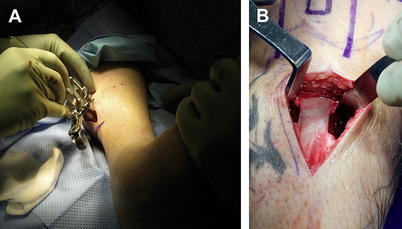

Vulpius and Stoffel20 introduced the gastrocnemius recession in 1913, transecting the gastrocnemius aponeurosis with a chevron cut and incising the deep fibers of the soleus. Several surgical variations have been described since. Silfveskiold released the gastrocnemius from its origin on the femoral condyles and repositioned the muscle below the knee.21 Strayer22 performed a transverse sectioning of the gastrocnemius aponeurosis where it attached to the underlying soleus aponeurosis. Baker23 modified the Vulpius procedure and described a tongue-and-groove recession. Lamm and colleagues24 describe a technique similar to Vulpius, but modified the technique by making a single transverse cut, rather than a single cut or multiple chevron cuts. Endoscopic procedures have emerged as an alternative to the open technique (Fig. 1).25,26

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree