Essentials of Diagnosis

- Raynaud phenomenon (RP), a vasospastic reaction to cold temperatures or emotional stress, leads to sharply demarcated color changes of the skin.

- Classified clinically into primary or secondary forms.

- Primary RP is idiopathic and is associated with no identifiable abnormalities in blood vessel architecture.

- Secondary RP patients may have complications of digital tissue ischemia, including recurrent digital ulcerations, rapid deep tissue necrosis, and amputation.

- Avoidance of cold temperatures is critical in the management of RP. The entire body must be kept comfortably warm.

- Medications are indicated if there are signs of critical tissue ischemia (eg, digital ulcers) or if quality of life is restricted.

General Considerations

A unique circulatory system, including both thermoregulatory and nutritional blood vessels, exists in the skin, especially in the hands, feet, and the face. In these areas of the body, local blood flow is regulated by a complex interaction of neural signals, cellular mediators, and circulating vasoactive molecules. Temperature responses are principally mediated through the sympathetic nervous system by rapidly altering blood flow through arteriovenous shunts in the skin. During hot weather, these shunts open (vasodilate), allowing heat to dissipate. In cool weather, the shunts constrict, shifting blood centrally and helping maintain a stable core body temperature.

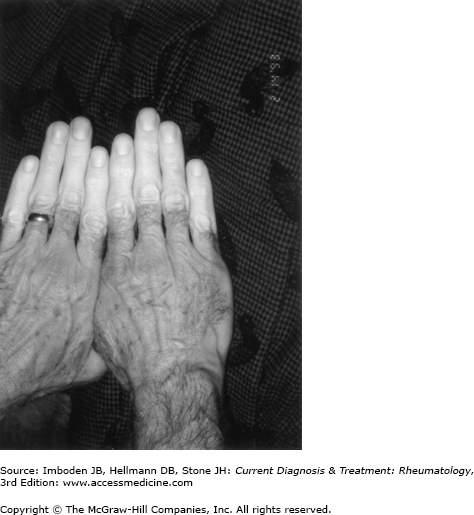

Raynaud phenomenon (RP) is transient digital ischemia due to cold temperatures or emotional stress. This vasoconstriction of digital arteries, precapillary arterioles, and cutaneous arteriovenous shunts leads to a sharp demarcation of skin pallor or cyanosis of the digits (Figure 24–1). The ischemic phase is followed by recovery of blood flow that appears as cutaneous erythema, secondary to rapid reperfusion of the digits.

RP is classified into two categories: primary and secondary. Primary RP are vasospastic attacks precipitated by cold temperatures or emotional stress. Primary RP, which occurs in the absence of an identifiable disease, is most common in otherwise healthy females between 15 and 30 years of age. A family history of first-degree family members is reported in about 30% of cases. These attacks usually occur symmetrically and bilaterally in the hands. There is no underlying sign of tissue necrosis or gangrene (eg, digital pitting) and the underlying vasculature is normal. Nailfold capillary microscopy (see below) and physical examination findings are normal. If a patient meets criteria for primary RP and no new symptoms develop over 2 years of follow-up, the development of secondary disease is unlikely. The finding of abnormal nailfold capillaries on microscopy or specific autoantibodies are strong predictors of secondary RP due to an underlying rheumatologic disease.

Secondary RP is associated with an underlying pathology that alters regional blood flow by damaging blood vessels, interfering with neural control of the circulation, or changing either the physical properties of the blood or the levels of circulating mediators that regulate the digital and cutaneous circulation. Among the large number of suspected causes of secondary RP, the most likely causes are systemic sclerosis (SSc), systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), Sjögren syndrome, or dermatomyositis. Patients with secondary RP generally have more severe, painful RP. This may be associated with evidence of digital ischemia, including fingertip ulceration and tissue loss.

Clinical Findings

All patients with a history of RP should be asked about symptoms suggestive of an autoimmune disease, such as arthritis, dry eyes or dry mouth, myalgias, fevers, rash, or shortness of breath. Careful physical examination for signs of immune-mediated digital ischemia should include examination of the pulses, auscultation over large arteries (eg, the subclavians), and nailfold capillary microscopy. The patient should be evaluated for specific autoantibodies if an underlying autoimmune disease is suspected (see Laboratory Findings).

RP most often affects the fingers, although attacks also occur in the toes and occasionally on areas of the face. A typical RP attack is characterized by the sudden onset of cold digits associated with a demarcation of skin pallor (white attack) or cyanosis (blue attack). After rewarming, there is vascular reperfusion, resulting in the erythema secondary to rebound of blood flow.

A diagnosis of RP may be made if a patient has a history of both cold sensitivity and associated color changes of the skin (pallor or cyanosis or both) limited to the digits. The diagnosis of RP can be made by asking the following questions: (1) Are your fingers unusually sensitive to cold? (2) Do your fingers change color when they are exposed to cold? (3) Do they turn white, blue, or both? The diagnosis of RP is confirmed if there is a positive response to all three questions but is excluded if responses to questions two and three are negative.

RP attacks typically start in a single finger and then spread to other digits of the same or both hands. The index, middle, and ring fingers are the most commonly involved digits. White attacks may lead to critical digital ischemia. In contrast, blue attacks are mainly the result of vasospasm of the thermoregulatory vessels. Low blood flow to the digits may persist for 15 minutes after rewarming. Physicians should pay careful attention to painful RP attacks because they are a symptom of ischemia.

Patients with clear clinical evidence for primary RP do not need further laboratory testing. This includes patients with symmetric attacks, no evidence of peripheral vascular disease, no tissue gangrene or digital pitting, and a negative nailfold capillary examination. However, if a secondary cause of RP is suspected, specific blood work is guided by the clinical findings associated with RP and should include serum chemistries, a complete blood cell count, thyroid function tests, serum and urine protein electrophoresis, and testing for cryoglobulins or cryofibrinogens. In addition, elevated inflammatory markers, such as the erythrocyte sedimentation rate or C-reactive protein, are associated with some but not all causes of secondary RP. (SSc, for example, is seldom associated with elevated acute phase reactants [see Chapter 25].)

Antinuclear antibody (ANA) testing is useful for evaluation of autoimmune diseases. In a study of 586 patients monitored for approximately 3200 person-years, a positive ANA assay was one of the strongest predictors of progression to SSc. The pattern of ANA can provide clues to the underlying autoimmune disease. An anti-centromere pattern detected on ANA testing is associated strongly with limited scleroderma (eg, the CREST [calcinosis, Raynaud phenomenon, esophageal dysmotility, sclerodactyly, telangiectasias] syndrome. Anti-topoisomerase antibodies are found in patients with diffuse SSc. Anti-dsDNA, anti-Ro/SS-A, anti-La/SS-B, anti-Sm, and anti-RNP antibodies are most characteristic of patients with SLE (see Chapter 21), Sjögren syndrome (see Chapter 26), or mixed connective tissue disease. Anti-Jo-1 and other anti-synthetase antibodies are often associated with inflammatory myopathies (see Chapter 27).

Examination of nailfold capillaries is important for the differentiation of primary and secondary RP. To perform nailfold capillary microscopy, a drop of grade B immersion oil is placed on the patient’s skin at the base of the fingernail. This area is then viewed using an ophthalmoscope set to 40 diopters or a stereoscopic microscope. Normal capillaries appear as symmetric, nondilated loops. In contrast, distorted, dilated, or absent capillaries suggest a secondary disease process. Abnormalities of the nailfold capillaries are strong independent predictors of rheumatic conditions, particularly SSc, SLE, and dermatomyositis.

Differential Diagnosis

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree