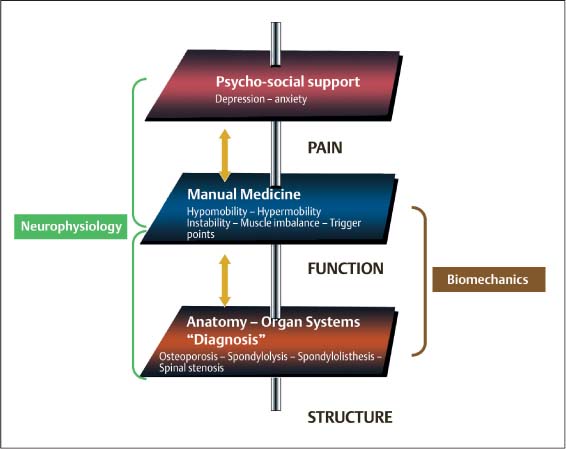

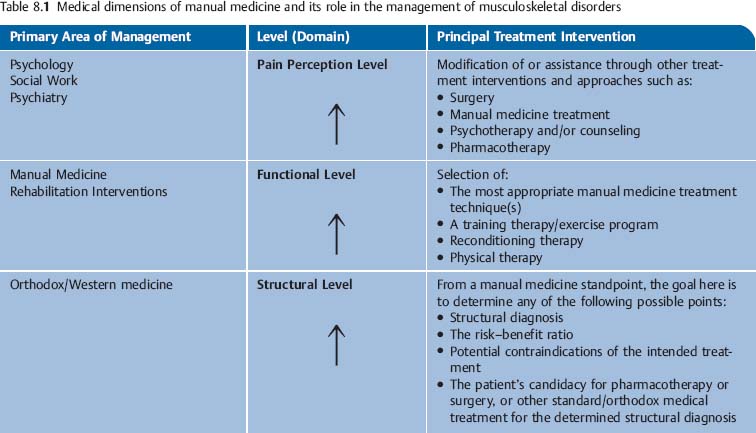

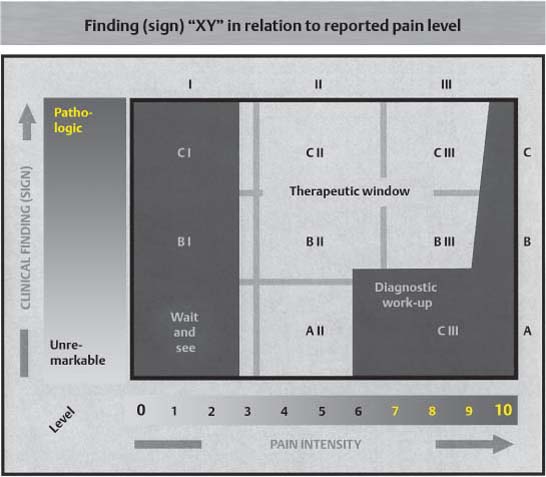

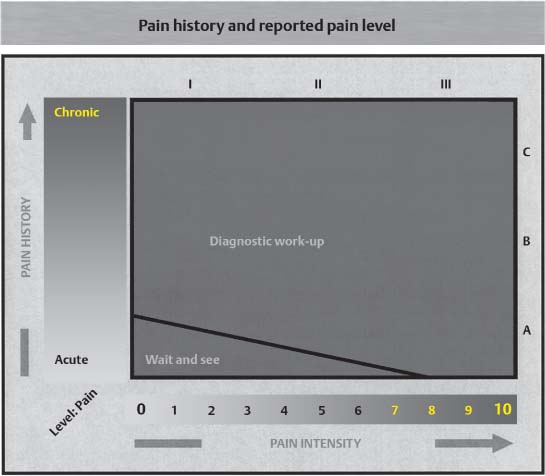

8 Rational Selection of Appropriate Low-Risk Treatment Interventions The etiology of many musculoskeletal disorders is much more often multifactorial than the result of a single cause. This is particularly true when a patient presents with low back or neck pain. Despite tremendous international research efforts, there are but a few scientifically tenable studies to date that have successfully identified the low-risk treatment intervention (s) that would be the most appropriate for a particular clinical presentation. Perhaps this is because of the complex nature of the topic itself. Certainly the many obvious and not so obvious interrelationships spanning the entire bio-psycho-socio-emotional spectrum require the individual study methodologies to be “as clean as possible.” Especially when it is impossible to come to a clear-cut anatomic or pathologic structural diagnosis, one would be safest to assume that it would be easier to conduct a useful study on what is thought to be a “simple” or “straightforward” clinical disorder than a more complex one. For example, compare the diagnosis of an anterior cruciate ligament tear with that of pain in an elderly patient who has been shown to have lumbar spinal stenosis secondary to degenerative changes and a preexisting scoliosis. It would seem easier to elaborate specific diagnostic criteria, therapeutic approaches, and quality control data for a torn ligament than for such diagnosis as spinal stenosis. Treatment, and in particular rehabilitative efforts, for many musculoskeletal disorders often present as a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge. While it is typically pain and the associated loss of function that prompts a patient to seek medical help, the physician’s job is to “start from the bottom up,” that is, searching for structural and objectively verifiable findings first, before looking for any functional issues that may then have led to the patient’s pain perception. This seems to be particularly true when trying to get a handle on the chronic or “overuse” conditions. Based on clinical experience across various specialties, the authors of this text have found it useful to approach an apparently complex clinical presentation in an organized manner, using a rational step-by-step approach: 1. First, as many as possible relevant clinical parameters or data points (objectively verifiable findings) are gathered and identified that pertain to a particular clinical situation. These objective findings are based on: (a) Thorough history. (b) A detailed physical examination. 2. Subsequently the particular signs and symptoms are: (a) Evaluated as to their relevance and significance. (b) Correlated with any objectively verifiable data points (adjunct diagnostic studies or laboratory values, provocation testing, etc.). (c) Integrated within the greater clinical context so as to arrive at a tenable clinical diagnosis (assessment, clinical impression) that takes into account the following: (i) Structural abnormalities. (ii) Functional deficits. (iii) Patient pain perception. To remain mindful of the various factors at play in any given clinical situation we have found it helpful to structure our thinking according to three major levels or domains, which in turn, are further divided into to specific subcategories or areas. The three main levels or domains are: 1. The structural level (“structure” domain). 2. The functional level (“function” domain). 3. The pain perception level (“pain” domain). Recent years have witnessed a plethora of “alternative”—often proprietary—treatment techniques that claim to be “holistic” and all-encompassing in the treatment of the various musculoskeletal disorders. Many a “new” technique often appears to be championed by one particular practitioner or school of thought. In isolated cases such a technique may have indeed provided some reported benefit, and the temptation is to “generalize” the success to other clinical situations as well, without appreciating the individual patient’s entire bio-psycho-social situation. By addressing usually only one level, and making claims that in the final analysis are clinically or scientifically unsubstantiated, many of these “healing cures” fail to adequately work up and treat the patient’s condition within the necessary medical as well as individual bio-psycho-social context. The structural level concerns itself with the organic, mostly the organic diagnoses that are typically based on objectively verifiable findings, such as disk herniation, osteoporosis, spondylosis, spinal stenosis, spondylolisthesis, and others. The structural level has been the domain of orthodox or “Western school” medicine (Fig. 8.1). The structural level corresponds roughly to the World Health Organization (WHO) definition of an “impairment,” which is defined as an abnormality of anatomical or physical structure. However, the WHO definition also includes psychological and cognitive impairments. Examples of impairments are hemiplegia, amputation, decreased range-of-motion, dysarthria, depressed mood, and aphasia. The construction of the appropriate treatment plan is determined by the individual patient’s clinical diagnosis, which in turn is based on specific meaningful structural and objective signs, known risk factors, indications, and contraindications. The functional level concerns itself with those components of the musculoskeletal system that impact upon the individual patient’s overall physical performance. Once a detailed structural and functional examination has been performed, which includes specific provocation and manual medicine evaluation maneuvers, the treatment approach is constructed. The treatments that specifically address issues associated with the functional level include manual medicine treatment, training therapy, trigger point treatment, reconditioning programs, and other related restorative–therapeutic interventions. Treatment outcome is maximized when the therapy concepts suggested by the structural level are coordinated with those arising from the functional level. If there are known structural deficits, the functional program must always take them into account and the program should be modified accordingly. When choosing the individual patient’s treatment interventions, the benefits and potential therapeutic risks as well as contraindications should always be weighed. The functional level is similar to the WHO’s definition of “disability,” which entails a description of the limitation of normal everyday activities such as dressing oneself. The functional level also includes the WHO definition of “handicap.” A handicap is a limitation on full participation in the community because of disability or impairment, such as driving to one’s usual workplace. Both terms concern themselves with the functional limitation that arises from a fundamental structural impairment. In virtually all of the musculoskeletal disorders, the pain perception level takes on a key role if not the key role. Even though the patient may have had significant functional deficits over a prolonged period, it is often the patient’s reported pain that prompts the medical visit. From a long-term view, the resolution or diminution of the patient’s pain can only occur when there is demonstrated improvement on both the functional level and the pain perception level. In any event, the selection of the appropriate therapeutic interventions should follow a logical progression. The indications and contraindications for one form of treatment versus another are determined by the findings from the structural level. The goals for manual therapy and a reconditioning program are based on the findings arising from the functional level (Table 8.1). Fig. 8.1 The structural, functional, and pain perception levels and their components as related to disorders of the musculoskeletal system. Once the various findings from the structural, functional, and pain perception levels have been collected and analyzed within the context of the entire clinical situation, the appropriate therapeutic modality or modalities are chosen. As with any other form of medical intervention, the primary goal is to maximize the beneficial treatment outcome while minimizing the potential risks. The following schematic presentations are intended to provide a rational basis for the selection of an appropriate management approach. The findings determined on the three different levels are correlated with the patient’s pain score, and a “therapeutic window” is opened for the appropriate therapy. If the patient has findings on all three levels, then therapies should be chosen that are recommended in the different “therapeutic windows.” The therapeutic window is reduced if additional adjunctive studies, such as the various imaging or laboratory studies, narrow the differential diagnosis. On the other hand, in some clinical situations, one may with good conscience suggest a “wait-and-see approach,” in which the individual patient’s course is monitored clinically over a certain period (follow-along). This should be particularly useful when dealing with a “case” of known self-limiting disorders (Fig. 8.2). If the clinical findings established for one level are strongly suggestive of a particular structural diagnosis, then the appropriate diagnostic and therapeutic management plan is directed to address these findings as specifically as possible. This may require that the patient be referred to the appropriate medical specialist or for specific diagnostic studies. Fig. 8.2 Correlation of pain intensity (I–III) and objective examination findings (signs) (A–C). Pain alone that occurs in the absence of any objectively verifiable clinical findings and that cannot be attributed to either the structural or the functional level is not by itself sufficient for the initiation any manual medicine intervention, physical or training therapy, or a reconditioning program (Fig. 8.3). When a patient presents with an extensive history of chronic unresolved pain, despite rational previous management, the entire bio-psycho-social situation should be taken into account before another isolated intervention is introduced. Manual medicine examination of a child with a so-called “school headache” reveals the presence of a painful, segmental somatic dysfunction in the cervical spine, a finding that correlates with the functional level. In this situation, it would be most appropriate to treat the child with mobilization with impulse techniques, for instance. It would also be appropriate to enroll the child in an individually tailored home exercise program and/or reconditioning program if indicated. If in another child with a similar pain history there are no meaningful findings elicited in the history and a sufficiently detailed physical examination, the child’s psychosocial situation both at home and in school should be evaluated. Treatment using manual medicine techniques is clearly not indicated in this situation Well-localized pain that is reported by the patient upon induced palpatory pressure near or at an irritation zone (or other similar localizable regions or “points”) is one indication for the use of manual intervention, such as mobilization-with-impulse techniques (the classic “thrust” techniques, for instance) or the nonimpulse technique, depending on the clinical situation. Pain in a characteristic pattern of distribution may be an indication for myofascial trigger point treatment, in particular when the snapping type of palpation is able to reproduce the patient’s described pain (e. g., manual evocation of a myofascial trigger point). A rather diffuse nonlocalized pain that is elicited even with the most gentle palpatory pressure on the skin and soft tissues typically requires a closer look at the patient’s pain perception level in order to determine whether there are any neuropathic, sympathetic reflex dystrophic, or psychosomatic contributions to the patient’s pain (Fig. 8.4). Fig. 8.3 Correlation of pain intensity and reported pain history.

Introduction

The Structural Level

The Functional Level

The Pain Perception Level

Examination Levels in Relation to the Diagnosis and Treatment of Musculo-skeletal Disorders

Correlation of the Various Clinical Parameters

Pain History and Pain Intensity (Fig. 8.3)

Example

Case A

Case B

Palpatory Evaluation and Potential Pain Provocation

Example

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree