Professionals as good citizens: responsibility and opportunity

Objectives

• Discuss what a caring response entails when the “patient” is the public at large.

• Describe four criteria of moral courage expressed by people who act courageously.

New terms and ideas you will encounter in this chapter

good citizenship

civic responsibility

spheres of moral agency

shared fate orientation

self-realization

service ethic

public interest versus common good contributions

moral courage

civic self

global citizen

Topics in this chapter introduced in earlier chapters

| Topic | Introduced in chapter |

| Professional role | 1 |

| A caring response | 2 |

| Professional responsibility | 2 |

| Agency | 3 |

| Moral agency | 3 |

| Moral distress | 3 |

| Utilitarian theory | 4 |

| Ethical reasoning | 4 |

| Deontology theory | 4 |

| Duties and principles | 4 |

| Nonmaleficence | 4 |

| Beneficence | 4 |

| Ethics of care | 4 |

| Virtue theory | 4 |

| Solidarity | 16 |

Introduction

Finally we come to the last chapter in this study of ethics, and it is fitting that its focus is back on you: you the health professional, but also you the citizen. Good citizenship is of course everyone’s responsibility, and the activities that express good citizenship are captured in the idea of civic responsibility. Both “citizen” and “professional” are labels that carry assumptions about a person’s role in society. Being a good citizen and being a good professional do have much in common. For example, each requires a measure of conscientiousness, engagement with societal needs, communication skills, and a willingness and ability to work with and on behalf of others.

Many interesting questions surround this dual role. For example, does your professional training provide you with any special opportunities and imply any special duties and responsibilities as a citizen? What is your special role, if any, that makes you the most appropriate person to take leadership on a civic issue that affects your community? Do you owe anything to society because it has bestowed on you the privileges of being a “professional,” a status that has always been held in high esteem in Western cultures? If asked, are you morally obligated to respond to a pressing civic need, or can you just say no? There are certainly civic situations from which you are not exempt because you are a professional, such as paying taxes and jury duty. Are you a professional person 24-7, or can you blend into society as an ordinary citizen, leaving any special tugs on your moral conscience at your professional workplace? We attempt to address all these questions in this chapter.

To help focus our discussion, consider the following story.

Reflection

Does the action that Michael and his physician colleague have taken so far demonstrate any special character traits that a good citizen would not also have (so that you would have to attribute it to their being health professionals)?

_____________________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________________

As you reflect on it further, is anything required of them as a duty because they are health professionals that would not also be required of any ordinary citizen?

_____________________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________________

Anyone reading about the situation probably feels that Michael and his physician colleague are responsible, caring citizens. He did not just ignore the worrisome thing he encountered, leaving a question about whether his children or other members in the community were at risk. But this does not distinguish him from any caring citizen. Nor does it answer the question as to whether there is anything in his and her roles as health professionals that made them uniquely responsible to decide to pursue the matter over the responsibility of, say, a housewife, or CEO of a company or a plumber who stumbled on to the same situation. We personally believe that the professional role per se seldom sets professionals uniquely apart from other caring citizens, although there may be some exceptions to this general rule of thumb. Some good thinking about this very issue has been done, and we welcome sharing key aspects of it with you here. We will examine the now familiar idea of seeking a caring response to gain insight into how and why your civic responsibilities will sometimes emerge from or combine with the fact that you are a professional. We will also explore how in some situations your opportunities to contribute to society’s well-being will be enhanced because you are one.

The goal: a caring response

Two basic ethics notions presented early in this book help to provide a paradigm of understanding for what constitutes a professional’s caring response to civic issues. The first is the idea of moral agency, accenting situations in which you can be expected to take charge. The second is the concept of professional responsibility.

Spheres of moral agency

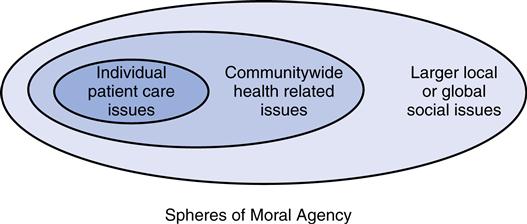

As you recall, the important concepts of agency and moral agency were introduced in Chapter 3 and have been reinforced time and again throughout the book. To review briefly, agency means that you have an authoritative voice in a matter and are in a position to legitimately exercise that authority. You are in charge, and for a reason that you and society affirm. Approaching your role as a moral agent as having spheres of moral agency provides a way to distinguish different kinds of circumstances where you might become involved in civic issues (Figure 17-1).1*

As a professional, direct patient care decisions that fall within your area of professional expertise represent the major focus of your agency. Because there is a moral dimension to direct health care service, in Sphere One, your professional actions clearly are as a moral agent.

A second sphere of authority exists when you encounter a situation that is not direct patient care but you have important knowledge, insight, or skills that can help to effectively address the issue. In Sphere Two, the more your role as a professional prepares you better than any other group in society to address it, the more you will be looked to as an authority. For example, the more education a dietician has on the effects of snack food on childhood obesity, the more other parents on the school PTA board will look to her for advice regarding the proposed debate to institute a public mandate regulating the vending machines contents. When there are deep values involved, you are viewed as a moral agent by fellow citizens in this second sphere of your activity. A current trend in some Western nations reported in the International Social Work2 journal is the movement from professional organization-based to citizenship-based regulation of traditional professions, one effect of it being the decreased distinction between the professions and citizens. This trend relies on the idea of traditional professional expertise to help enrich the understanding of what a professional really contributes but in other ways decreases the difference between professional and citizen characteristics. If this trend increases, the second sphere of moral agency may rely heavily on the expertise of professionally prepared citizens such as you are preparing to be, but your authority will be around your area of knowledge and skills only. Over time, agency could spread to rely less on the difference between professional and citizen.

The outermost Sphere Three shifts the emphasis from your knowledge and skills base to the fact that professionals are held in high regard in society. Health professionals, lawyers, religious leaders, and others often have a high status, even though they become the brunt of deep criticism when they do not stand up to society’s realistic (or even unrealistic) expectations. Often, the gravity or urgency of a situation is expressed more forcefully when professionals get behind the cause and provide leadership in endorsing it. This is seen in everything from television ads to appeals for financial contributions for societal issues. Your voice can influence the outcome by virtue of being a professional, although you may have little significant or unique knowledge that situates you as an authority. In this sphere, you represent someone who is worthy of being taken seriously; therefore, you become an authority by virtue of your societal status. Again, when the issue involves societal values, which it almost always does, you are seen as a moral agent.

These three spheres provide general guidelines for the relationship of your role as a professional to your role as a citizen. As you can probably quickly conclude, there are not hard and fast boundaries separating these three spheres. Your clinical expertise may be operative in any of them to some degree, and your position of high regard in society supports activity at the very core of your decision-making authority.

A second conceptual notion that you were introduced to in Chapter 2 is essential in helping you to further fine-tune your civic priorities.

Professional responsibility: accountability and responsiveness

Your responsibility as a professional must be calibrated according to a combination of accountability and responsiveness to a situation. All too often responsibility is viewed solely in terms of accountability, reducing responsibility to a duty that is inherent in the idea of professionalism and suggesting that when an opportunity to act arises you are obliged to do so. The standards of accountability by which you are measured range from the dictates of your professional codes, to patient care standards established by your profession and other licensing bodies, to institutional policies. You can see that in the center Sphere One of moral agency (concerned with direct patient care) they are appropriate and, in fact, designed for that purpose.

As you consider becoming involved in the other two spheres, the companion idea of responsiveness also is critical to understanding your actual responsibility. Being responsive means being relational at a deeper level that requires sensitivity to and understanding of the other or others who will be impacted by your action. The urge to act must be balanced with detailed attention to the narrative or human story you are encountering and with it, a genuine humility reminding you that your professional expertise does not prepare you to be an expert in every societal problem that falls into your path. As you continue outward towards Spheres Two and Three, your experience as a citizen and as a professional coincide more fully. In the second, you may quickly discern whether or not the type of health-related problem you encountered as a societal issue draws quite closely on what you know from your professional training. If yes, you can more closely identify with the details of the situation and what should be done.

As you move into Sphere Three, you are increasingly acting as a citizen who is a health professional. Yet, others may view you primarily as a health professional because most people think of professionals as being a doctor, or lawyer, or pharmacist or other professional 24-7. For example, if you have not already been prodded for your professional advice when someone recognizes you at a supermarket check-out counter, at a party, or elsewhere on the street, we can guarantee you will be. However, your professional identity is at work in Sphere Three only as a member of a citizenry who is granted moral authority on the basis of your societal position. You are not drawing on the content of your professional training and you will be acting more fully on what you know and can learn in the same way as any other citizen who becomes involved in societal issues.

The six-step process in public life

Michael and his physician colleague are not faced with a clinical or health policy situation in the same regard that we have invited you to explore the professional’s involvement in them in other parts of this book. They may have no thoughts at this point about whether their decision to try to get at the root of a problem they believe is potentially causing harm to their community is related to their professional roles. Their lack of imagination or reflection on this issue is understandable because the health professional’s idea of “care” usually is thought of as being contained to situations between individuals. Yet they feel as if they should do something as citizens, and we can assume that they are being driven in part by a motivation that they should be of service whenever they can. There is a lot of writing about this motivation among professionals, one aspect of which we present briefly here through the lens of different kinds of careers.

We touched on the career choice issue in Chapter 16 when a part of Eino Maki’s situation was analyzed from the point of view that he was in a job open to him as a worker with some societal strikes against him, and you met Jane Tyler who was trying to increase her life options through the financial aid she had been granted to realize a career. All professionals fall within the category of having had an opportunity to choose a career, an option not open to most of the world’s population. Having a career choice means that you are able to pursue your specific tastes, framing a life plan to suit your own character. Norman Care’s3 classic article on the nature of careers suggests that people choose between two basic types of careers: those with a shared fate orientation and those oriented to self-realization. The former focuses on service to society, the latter solely on self-satisfaction.3 Health (and other) professionals fall within both categories to some extent but primarily are in the shared fate category, with its straightforward service ethic, or inclination to be of service. This inclination again has been revisited recently from a sociological analysis of the utility of the professions in the 21st century workforce that you are entering.4 In short, both from a personal leaning towards helping others and from a pragmatic consideration of our usefulness, the idea of service is deeply engrained in many professionals.

Now that you have been introduced to the three spheres of moral agency, each involving a caring response, and reminded of the idea of professional responsibility, you have an expanded framework to think from as we walk with Michael and his colleague through the six-step process of ethical decision making regarding this opportunity to be of service.

Step 1: gather relevant information

What information do we have?

Michael knows there is a deadly toxin in the stream near his home and other homes in their neighborhood. Every action he has taken so far suggests that he knows this is not a benign situation; rather, it is a problem that should arrest the attention of others. He surmises, though does not have certainty, that something more is going on, perhaps an attempt by other leaders in the community to cover up any wrongdoing by the ExRad corporation that has brought needed jobs. His suspicion is shared by his physician friend who has offered to link arms with him in pursuing the issue. They are concerned just as any other good members of the community would be concerned.

However, we know that these two individuals also are not like many other citizens in the community. It stands to reason that they have been exposed in their professional training to some understanding of how various environment pollutants affect health. As a pharmacist, Michael may have quite specific information about the toxic effects of trichloroethylene. At the very least, they have ready access to literature that will inform them in technical language they can more readily comprehend than many ordinary citizens. Whether or not they have direct knowledge of how polluted water supplies are damaging the health of whole communities, we do not know for sure. But we do know that starting about a decade ago, the World Health Organization made waterborne sources of ill health one major focus worldwide5 and that this type of information is broadly being researched and the findings disseminated to medical and other health professions who provide direct patient care.6 From just these perspectives alone, we can assume that Michael and his colleague’s moral agency would fall more fully within the second sphere of professional responsibility to become involved in this civic issue than if the issue involved a heavily used bridge whose construction may be called into doubt by some members of the community.

We can also safely assume that this doctor and pharmacist are in a position to be heard if they speak up. The fact that the official took Michael aside and quietly implied that he not pursue the issue further suggests that he knew Michael and the physician could call attention to ExRad’s conduct. They work in a relatively small town, a type of closely knit community usually loyal to their professionals. Michael belongs to the Rotary Club, a social and service organization to which leaders in a community must be invited by other leaders. Their roles carry a certain amount of status and weight in relation to most citizens. So, all things being equal, they can be viewed as moral agents in this situation in the third sphere by virtue of their status and role.

However, there is another human dimension that informs Michael’s situation. It depends on his having grown up with these people. In discerning his professional responsibility, accountability is one thing, but then there is responsiveness at a more detailed level. He can be sensitive to nuances of this community that others would not be able to detect. For one thing, he knows how much the livelihood of this community does depend on jobs and the fragile line between abject poverty and at least minimal needs being met. ExRad is meeting an essential economic need. Michael knows that while he is “one of them,” he also jumped ship and went to live in, of all places, New York City. Having come back, he is welcomed on the one hand as “a hometown boy who made good” but also may still be viewed with suspicion as an “outsider” who can be dismissed (and discriminated against) as a troublemaker. He and his family may become ostracized, even if his concern about ExRad is proven to be correct. So, he is hesitant about what to do next, not because he is ignorant of his or his colleague’s power but because they understand that getting into this issue may be a messy business.

Finally, he and his colleague are faced with uncertainty about the outcome of their endeavor. They know they may be able to prove nothing.

Reflection

Are there other types of information you would consider relevant but that we have not touched on? If so, what are they?

_____________________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________________

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree