Despite early treatment efforts, many patients with Perthes disease are left with residual femoral head deformity, which can be symptomatic with a residual limp and poor hip motion. Many such patients can be treated using an extra-articular femoral osteotomy. Selecting treatment methods for patients with symptomatic Perthes disease with healed but deformed femoral heads has always been difficult but is now even more complex because of the new possibilities of femoral head–neck recontouring and femoral head reduction surgery. Occasionally, patients develop osteochondritis dissecans when there is little femoral head deformity. The primary objective of management is to establish the exact cause of pain and address that cause specifically. This article outlines an approach to these patients.

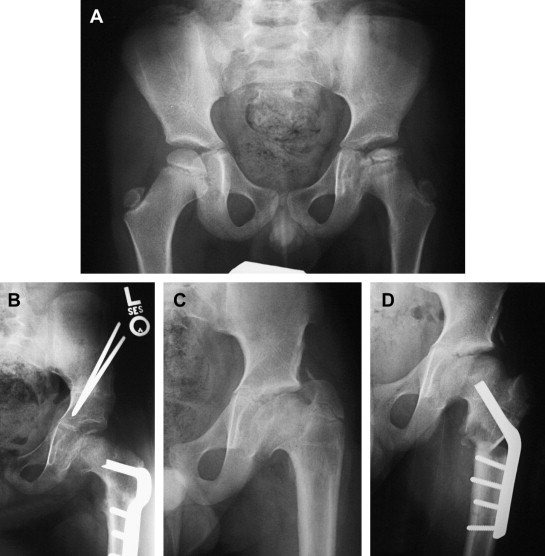

Despite early treatment efforts, many patients with Perthes disease are left with residual femoral head deformity that can be symptomatic with a residual limp and poor hip motion. Containment treatment to restore sphericity of the femoral head is inappropriate in such cases. Selecting treatment methods for symptomatic patients with Perthes disease with healed but deformed femoral heads has always been difficult ( Fig. 1 ) but is now even more complex because of the new possibilities of femoral head–neck recontouring and femoral head reduction surgery. Occasionally, patients develop osteochondritis dissecans when there is little femoral head deformity. The primary objective of management is to establish the exact cause of pain and address that cause specifically. This article outlines an approach to these patients. An outline of possible choices is presented in Box 1 .

Extraarticular methods

- •

Intertrochanteric valgus osteotomy

- ○

Valgus extension: best corrects limb deformity

- ○

Valgus flexion: may better correct anterior impingement

- ○

- •

Trochanteric transfer with relative neck lengthening

- ○

To correct greater trochanteric abutment)

- ○

- •

Noncontainment acetabular procedures

- ○

Shelf acetabuloplasty

- ○

Chiari procedure

- ○

- •

Intraarticular methods

- •

Osteochondroplasty of the head and neck (open or via arthroscopy)

- ○

Note: residual dysplasia may also require treatment

- ○

- •

Femoral head reduction (central “down-sizing”)

- ○

Unproved method

- ○

- •

Excision of osteochondritis dissecans

- •

Labral repair

- •

Classification of sequelae

Although new methods for identifying the sequelae of Perthes are emerging in the era of “hip impingement,” the traditional Stulberg classification of the sequelae of Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease remains the standard. Stulberg and colleagues described a system of classification that predicts the risk for early osteoarthritis on the basis of hip joint shape and congruity. Early onset arthritis is uncommon when the femoral head is spherical (Stulberg I and II), but some of these patients may have impingement symptoms and labral tears that interfere with physical activities. Patients with late Perthes disease with Stulberg class III, IV, and V classification may develop early onset arthritis, but there are no current guidelines for prophylactic treatment.

Treatment of residual deformity with extraarticular procedures

Valgus Osteotomy to Correct Impingement and Improve Limb Position

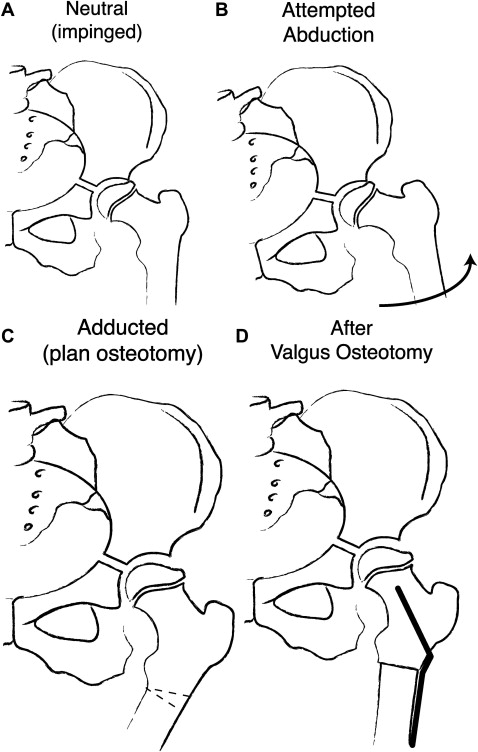

Catterall and others have defined methods for managing late femoral head deformity without entering the hip joint. These patients often have pain, a shortened limb, and a limp caused by the coxa vara resulting from severe Perthes disease ( Fig. 2 ). These patients sometimes have a flexion contracture with the leg held in adduction to avoid lateral femoral head impingement. Physical examination and radiographic examination can confirm the deformity and cause of symptoms. Often, abducting the hip causes discomfort and pelvic rotation because of the extruded femoral head impinging on the acetabular rim.

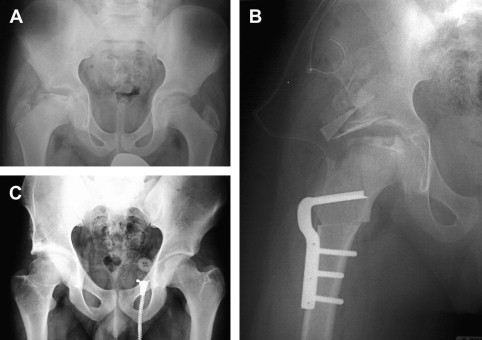

Such patients can be improved by extraarticular proximal femoral osteotomies. In planning for such an osteotomy, one obtains an adduction radiograph to confirm the position where the more medial portion of the femoral head better centers itself within the acetabulum ( Fig. 3 ). An MRI and an arthrogram may also be helpful in this assessment.

In most cases the operative procedure includes a proximal femoral valgus osteotomy, whose principle is to correct lateral impingement of the femoral head. The extension component of the femoral osteotomy is somewhat less important. The anterolateral impinging portion of the enlarged femoral head is left intact and not removed. This traditional philosophy differs from later treatment ideas, which are presented next, in which the femoral head and neck are recontoured.

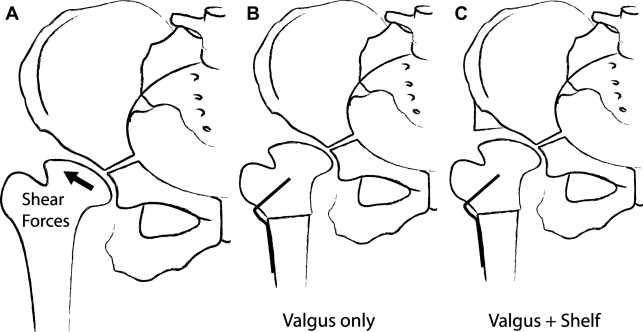

When significant valgus is performed, the hip is at some risk for instability and in such cases a shelf acetabuloplasty can be added to stabilize the hip joint ( Fig. 4 ). An added shelf acetabuloplasty supports the labrum and prevents any risk for residual subluxation ( Fig. 5 ). Decision regarding which patient should have a valgus osteotomy alone versus which might benefit by the addition of a shelf procedure to prevent femoral head subluxation has not been clearly established and requires experience and judgment.

The overriding principle of extraarticular osteotomy to prevent late deformity in Perthes disease is to reposition the limb so that the child can walk more normally without impinging the lateral segment of the femoral head. At follow-up most patients treated with valgus osteotomy have satisfactory flexion and extension, continued decreased hip rotation, but much improved hip abduction and a significant improvement in limb length difference. Parents and the patient are usually happy with the procedure because of the improvement in functional limb length difference and limp.

Most centers that treat patients with late Perthes disease have had satisfactory results with the procedure and have been slow to move toward femoral head reshaping procedures. One reason for this is that most patients with an enlarged femoral head have some acetabular dysplasia and if the femoral head is brought down to normal size, there is a risk for hip subluxation. Also, there has been less long-term follow-up regarding head–neck reshaping procedures in Perthes disease.

It is important for the surgeon to be aware of gradual knee valgus syndrome (secondary to chronic hip varus). Hip osteotomy can unmask the knee valgus and it may suddenly “appear” following surgery. One may have to warn parents of this phenomenon and may need to perform simultaneous medial–distal femoral stapling or acute distal osteotomy or possibly late distal osteotomy.

Greater Trochanteric Transfer (Relative Femoral Neck Lengthening)

Greater-trochanteric abutment is a major problem in many cases of healed Perthes for various reasons. In the nontreated cases it is more likely caused by trochanter overgrowth and relative coax vara with head flattening, whereas in surgically treated cases it is often related to varus osteotomy, which worsens an already existing proximal femoral varus deformity. With better understanding of the proximal femoral vascularity, the position of the soft spot, and subretinacular vessels, relative neck lengthening and trochanteric distalization have become successful tools in dealing with treatment of mechanical problems of trochanteric abutment and safe-trochanteric distalization.

Acetabular Procedures

It is important to note that true acetabular dysplasia can coexist in cases of Perthes disease as a morphologic response to the flat, elliptical, mushroom-shaped growing femoral head. An important technical point to note is that of potential iatrogenic acetabular undercoverage following femoral procedure, such as open femoral osteochondroplasty or head-reduction procedure. These can lead to hip instability caused by the relative imbalance in joint congruity from treating the femoral side and may require an additional acetabular procedure, such as the Bernese periacetabular osteotomy, to counteract instability.

Other acetabular procedures have also been reported for management of patients with sequelae of Perthes’ disease. Shelf acetabuloplasty has been reported as an alternative to proximal femoral valgus osteotomy for patients who have hinge abduction and severe Perthes disease. The Chiari osteotomy has been performed to relieve pain in patients with long-term sequelae of Perthes’ disease. The mechanism for pain relief is uncertain, but there may be an element of labral support and redistribution of weight-bearing forces that improve the mechanics of the hip joint when greater acetabular coverage is obtained. The acetabular dysplasia may need to be addressed in patients with healed Perthes, particularly those that present with typical features of dysplasia, such as sloping acetabular roof, hypertrophied labrum, or large labral tears.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree