CHAPTER 1 Principles for practice development

1. Describe the services provided by the wound specialist.

2. Identify a certification process that is legally defensible.

3. Distinguish between prevalence and incidence, addressing how each is calculated and the clinical utility of each measure.

4. Describe the data that are collected and used to drive practice and justify the wound specialist position.

5. Provide an example of two stakeholders and why they hold that position in a skin and wound care practice.

6. Cite three examples of how the wound specialist can affect cost savings within an institution.

Many factors contribute to a successful practice as a wound specialist. Obviously the specialist must have a strong knowledge base in wound care and the relevant pathologies. In addition, the specialist must establish credibility, which is earned by demonstrating clinical competence, critical thinking, organization, self-confidence, and an eagerness to collaborate and share information with colleagues. However, a successful practice also requires the wound specialist to integrate business skills to develop goals that reflect the organization’s mission and goals, effectively define services, identify benefits of services, outline a marketing approach to potential referral sources, and draft a conservative but realistic budget. Many decision-making tools and clinical resources are needed in a wound management program. The wound specialist would be wise to assemble a business plan for new skin and wound-related programs. Components of a business plan are listed in Chapter 2, Box 2-1. This chapter discusses the application of business skills in terms of qualifications, role development, time management, data collection, marketing, value-added services, and outcomes measurement.

Educational preparation of the wound specialist

When an organization is developing a skin and wound management program, it is incumbent upon the administration to demand appropriate educational preparation, qualifications, and credentialing of the health care professional who will function as the wound specialist. Appropriate education and certification should not be confused with attendance at individual seminars or continuing education courses. Upon completion of a continuing education course, the attendee receives a certificate of completion. However, in no way should this certificate of completion be misconstrued as an indication of the attendee’s expertise, mastery, or competence. The certificate simply denotes the individual’s attendance at the educational event.

National certification: value and routes

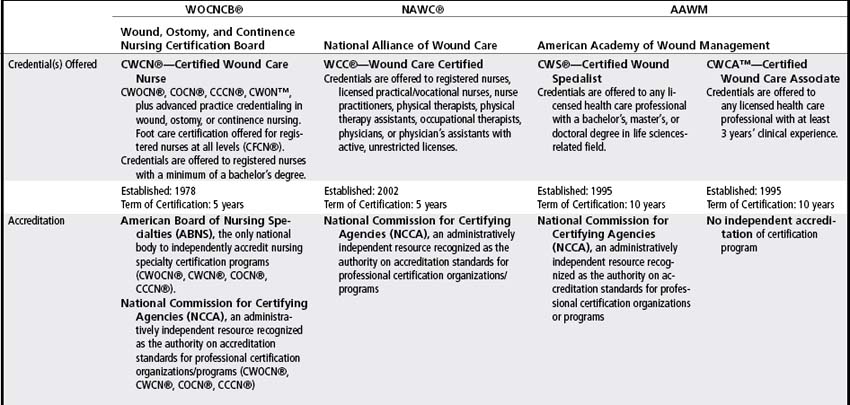

National certification yields many benefits to the individual, the employer, and the patient (Box 1-1) (Bonham, 2009; Cary, 2001; Fleck, 2008; Gray, 2008; Woods, 2002). National certification is the formal recognition of an individual’s knowledge and expertise in a defined functional or clinical area of care. National certification is intended to protect the public and should validate an individual’s specialty knowledge, experience, and clinical judgment. Table 1-1 presents a comparison of wound certification programs (WOCNCB, 2009). Because not all programs are legally defensible or psychometrically sound, the following critical components of the organization providing the certification are important to assess: national accreditation, eligibility criteria (educational degree, formal wound care education, structured clinical practicum in wound care, prior clinical experience), and recertification requirements. Collectively, these components influence the extent to which the certification designation is legally defensible (Hess, 2005). Checklist 1-1 presents questions to ask when comparing certifying organizations and certifications.

BOX 1-1 Value of Certification

Certified individual’s perspective

CHECKLIST 1-1 Questions to Ask when Comparing Certifications

✓ Is the credentialing organization accredited by an independent, national certifying body?

✓ Was a job analysis or role delineation study performed?

✓ Is the examination created by an individual or by a committee of content experts?

✓ Does the certifying organization’s mission agree with the mission of your work environment?

✓ Does the certifying organization provide self-assessment (or practice) to measure your professional knowledge and prepare you for the actual credentialing examination? (It must not teach the answers to the test.)

✓ Does the certifying organization require that the coursework be completed by an outside, accredited program focusing on wound care?

Eligibility criteria

A key distinction among the certification designations is the education and clinical experience criterion for eligibility. Eligible disciplines and their educational preparation differ among certifying organizations. For example, the designation CWOCN (Certified Wound, Ostomy, Continence Nurse) is bestowed only upon eligible baccalaureate prepared nurses, whereas other certifications are available to licensed practical nurses. Table 1-1 lists additional examples.

Recertification requirements

In the ever changing world of wound care and the need to stay current, recertification requirements must be considered and vary among credentialing organizations. Required frequency of recertification is 5 or 10 years, depending on the organization. Methods of recertification vary significantly and include self-assessment, proof of experience, and retesting.

Roles, functions, and responsibilities of a wound specialist

The wound specialist is not responsible for conducting every wound assessment or dressing change. Clarity in terms of expectations of the wound specialist, staff nurse, and physical therapist (PT) is essential to promote collaboration and deliver comprehensive and effective skin and wound care. This clear delineation of roles is important to foster an empowering environment, avoid duplication of efforts, and maximize the efficient use of resources, including personnel. Table 1-2 provides examples of role delineation of a wound specialist and a staff nurse.

TABLE 1-2 Delineation of Roles of Wound Specialist and Staff Nurse

| Wound and Skin Specialist | Staff Nurse |

|---|---|

| Facilitate creation and implementation of pressure ulcer risk assessment protocol. | Conduct risk assessment per protocol. |

| Establish protocol for prevention guidelines to correlate with risk assessment. | Implement appropriate risk reduction interventions. |

| Establish protocol for management of minor skin lesions (candidiasis, skin tears, incontinence-associated dermatitis, Stage I and II pressure ulcers). | Implement appropriate care of minor skin lesions. |

| Formulate skin and wound care product formulary to specify indications and parameters for use of products. | Use wound products per formulary. Notify wound specialist if product performs poorly or if expected outcome is not achieved. |

| Conduct comprehensive assessment, establish plan of care for complex patients (e.g., leg ulcers, stages III and IV pressure ulcers), conduct regular reevaluation of healing. | Notify wound specialist of complex patients. Conduct focused wound assessment. Implement appropriate care per wound specialist’s direction and facility protocols. |

| Provide competency-based staff education for new employees and annual competency-based education for existing employees. | Identify and recommend topics of interest for staff education and updates. |

| Track outcomes and identify skin and wound care issues. Initiate quality improvement activities. | Participate in quality improvement activities. |

Participation in staff orientation programs is a key strategy to communicate roles, functions, and responsibilities. This setting offers an opportunity to orient new staff members to their role in maintaining skin health, providing wound care, skin assessment and surveillance, risk assessment, and pressure ulcer prevention. The wound specialist should take the time to instruct personnel on when and how to access the wound specialist. Key stakeholders (e.g., physicians, information technology personnel, purchasing director, materials management, director of nursing) should be contacted and the role of the wound specialist discussed and clarified. Stakeholders, by definition, may affect or be affected by the skin and wound program; thus, keeping them involved and informed can minimize or eliminate negative ramifications. As with all discussions, emphasizing the benefits of the skin and wound care program to the success of the facility or patient practice is important. The support and confidence of key stakeholders are so critical that the extra effort and time taken to nurture these relationships are well worth it. Ultimately, however, the wound specialist will need to demonstrate competence and confidence in his or her practice. Regardless of the health care setting in which the wound specialist will practice, role implementation will share common components: clinical consultant/expert, educator, integrator of research and quality improvement, and leader/coordinator (Box 1-2).

BOX 1-2 Roles of the Wound Specialist

Consultant/expert

• Evaluates patient response to treatment and the progress of wound healing, making adjustments and modifications as indicated

• Where qualified and appropriate, provides conservative sharp debridement of devitalized tissue and applies silver nitrate to epibole, granulation tissue, and areas with minor bleeding

• Provides consultation and follow-up for patients with draining or chronic wounds, fistulas, or percutaneous tubes through outpatient clinic visits and/or phone consultations; initiates appropriate referrals for medical or surgical intervention

Educator

• Provides appropriate education to patient, caregiver, and staff regarding skin care, wound management, percutaneous tubes, and draining wound/fistula management

• Assists staff to maintain current knowledge and competence in the areas of skin and wound care through orientation and regularly scheduled education

• Attends continuing education programs related to skin and wound management

Change agent (see tables 1-3 and 1-4)

• Identifies barriers to change

• Provides evidence that persuades staff that change will achieve desired outcome

• Considers all stakeholders when planning change

• Communicates aspects of practice changes that will positively affect key stakeholders (especially the staff expected to implement the change)

Program coordinator

• Provides consultation and assistance to staff in developing and implementing protocols used in the identification and management of patients with potential or actual alteration in skin integrity

• Provides guidance to staff in implementation of protocols to identify, control, or eliminate etiologic factors for skin breakdown, including selection of appropriate support surface

• Establishes protocols and guidelines for appropriate and cost-effective use of therapeutic support surfaces

• Maintains records and statistics and submits reports to employer

• Analyzes inventory and recommends appropriate additions and deletions to ensure quality and cost-effectiveness of products used for skin and wound care

• Serves on agency-wide committees and participates in agency-wide projects as requested

Integrator of research and quality improvement

• Assists staff to maintain current state-of-the-art practice by reviewing and revising policies and procedures to be consistent with national guidelines and other sources of evidence-based literature

• Provides leadership with prevalence and incidence studies

• Conducts product evaluations or contributes to research studies related to skin and wound care when indicated; submits reports and recommendations based on results

Consultant

Although many wound specialists provide direct patient care for the most complex wounds, in most settings the wound specialist serves primarily as a consultant. As a consultant, the specialist can better meet the majority of the patients’ needs by coordinating a skin and wound care program implemented by a multidisciplinary team of health care providers. The consultant role builds on the foundations of the wound specialist’s clinical expertise in wound-related pathophysiology, physical assessment, wound assessment, appropriate use of interventions, and documentation. A successful consultant must effectively communicate, collaborate, and educate. Clinical decision-making tools and resources, such as protocols, product formularies, and standardized care plans, pave the way for the specialist to adopt a consultative approach within the organization (Pasek et al, 2008).

Educator

Knowledge about skin inspection, pressure ulcer prevention, basic wound care, and comprehensive, accurate documentation is essential to maintaining and restoring skin integrity. Information about wound and skin care is increasingly available from the literature and from commercial sources. Reimbursement restrictions provide greater incentive for staff to familiarize themselves with basic skin care and pressure ulcer prevention. However, the wound specialist needs to organize the information into retrievable and clinically useful formats so that a formulary of wound and skin care products is available, the process for selecting and ordering an appropriate support surface is specified, and the documentation is comprehensive, easily accomplished, and not repetitive. As an educator, the wound specialist will develop routine orientation sessions to introduce new staff to the pressure ulcer prevention program, covering, for example, basic wound assessment, support surface selection, and the essential nature of skin inspection and risk assessment.

By auditing chart documentation or surveying the staff’s knowledge about specific areas of wound care, the specialist can identify additional needs and target follow-up educational activities to satisfy those needs. Beitz, Fey, and O’Brien (1999) warn that “professional staff who perceive little need for additional wound care education may ‘tune out’ opportunities for increasing their knowledge base because they consider themselves ‘competent.’” The information underscores the importance of using pretests and other means of educational needs assessments; however, education does not guarantee practice change.

Change agent

Although education is an important role and tool for the wound specialist, it can be viewed as a burden that will increase workload rather than an innovation that eventually will decrease workload and improve patient outcomes (Landrum, 1998b). The organization will need to integrate principles for innovation adaptation to increase the likelihood of success with the educational efforts. An individual’s reaction to and decision about new information, ideas, or practice (i.e., innovations) develops over time and seldom is spontaneous. The Diffusion of Innovations Theory (Rogers, 1995) provides a framework for changing practices in a group, individual, or organization (Dobbins et al, 2005; Landrum, 1998a). This theory describes how people adopt innovations using five stages: knowledge, persuasion, decision, implementation, and confirmation. Whether the innovation is implementing a new product or improving upon an existing product, and whether the innovation is preventive or has immediate observable results, a failure to consider these stages can spell disaster and frustration. Table 1-3 outlines these stages, defines each stage, and discusses considerations relative to skin and wound care.

TABLE 1-3 Five Stages of Rogers’s Innovation-Decision Process

| Stage | Description |

|---|---|

| Individual becomes aware of an innovation and of how it functions. May occur with reading, reviewing posted flyers, attending lectures. | |

| Favorable or unfavorable attitude toward an innovation forms. To form a favorable attitude, the individual must be convinced that the innovation has greater value than current practice (e.g., identify patients at risk for pressure ulcers or target appropriate interventions). | |

| Individual receives enough information to form an opinion about innovation. Individual pursues activities that lead to adoption or rejection of the innovation. | |

| Once an individual makes a decision to adopt the innovation, barriers (structural, process, psychological) to implementation must be overcome (e.g., adequate number of forms is available). | |

| Individual seeks to reinforce his or her decision. Observable and positive results are critical at this stage to prevent a reversal in decision. Careful monitoring is required, and information validating positive effects is important (e.g., decrease in incidence of pressure ulcers after adoption of new risk assessment tool). |

Data from Landrum BJ: Marketing innovations to nurses, part I. How people adopt innovations, JWOCN 25:194, 1998.

Innovation is more likely to be adopted and behaviors changed when the innovation is perceived as relevant and consistent with the individual’s attitudes and the perceived attitudes of colleagues within the organization (Dobbins et al, 2005). Generally, an individual will seek like-minded peers who already have embraced the innovation to discuss the consequences of adopting the innovation, and an individual’s motivation to embrace the innovation is increased when these colleagues are supportive and positive about the innovation. Five attributes of an innovation significantly influence the rate at which the innovation is adopted: relative advantage, compatibility, complexity, trialability, and observability (Table 1-4). These attributes should be considered before the persuasion stage so that adjustments can be made to enhance the likelihood of success with the education efforts.

TABLE 1-4 Attributes that Influence Adoption of Innovation

| Attributes of Innovation | Description |

| Relative advantage | Is this better than an existing practice (e.g., potential decrease in costs, decrease in staff time, ease of use)? |

| Compatibility | Is this consistent with the individual’s existing values, experiences, and needs? |

| Complexity | Is this innovation difficult to understand or use? For example, when a protocol is developed that links risk assessment scores with nursing interventions, the decision about which preventive nursing intervention to use may be perceived as less complex than before the protocol; therefore, the protocol may be more likely to be adopted. |

| Trialability | Can the individual experiment with the innovation on a limited basis? |

| Observability | Are the results of an innovation visible to others? Subtle outcomes are harder to communicate to others, so the innovation often is slower to be adopted. |

Adapted from Landrum BJ: Marketing innovations to nurses, part 1. How people adopt innovations, J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 25:194, 1998.

Integrator of research and quality improvement

Evidence-based care.

Many individual and organizational barriers exist to research utilization and evidence-based care (DiCenso, Ciliska, and Guyatt, 2005; Webb, 2008). One individual barrier is a wound specialist who may feel inadequately prepared to evaluate the quality of research and lacks knowledgeable colleagues with whom to discuss research. In addition, the wound specialist’s access to the literature may be a hardship because of workload and time limitations. On an organizational level, barriers may arise from a lack of interest, motivation, vision, and strategy on the part of managers. Organizational barriers also may be related to library access, the extent of library holdings, and Internet access. Recognizing and overcoming these barriers is important in order to positively impact research utilization.

To embark on the path of evidence-based care, the specialist must keep abreast of relevant health care literature to “find the evidence.” In the face of a constantly growing body of health care literature, remaining current in the literature may seem impossible or all-consuming. However, practical information sources, referred to as preprocessed resources, are available that expedite access to evidence (Collins et al, 2005).

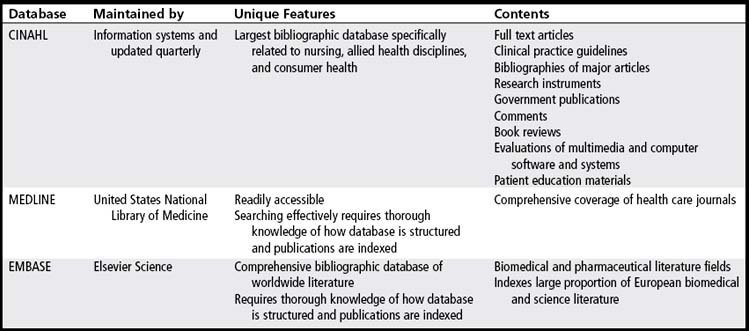

Preprocessed resources are products that have been developed by an individual or group that has reviewed the literature, filtered out the flawed studies, and included only the methodologically strongest studies. A hierarchy of preprocessed information sources with relevant examples is given in Table 1-5. Such sources include practice guidelines, clinical pathways, evidence-based abstract journals, and systematic reviews. For example, guidelines pertinent to skin and wound care have been published by the Wound, Ostomy and Continence Nurses Society (WOCN Society, 2002, 2003, 2004a, 2005a, 2010), the Wound Healing Society (Hopf et al, 2006; Robson et al, 2006; Steed et al, 2006; Whitney et al, 2006), the National Guideline Clearinghouse (www.guideline.gov), the National Medical Directors Association, and the Cochrane Collaboration (www.cochrane.org).

TABLE 1-5 Hierarchy of Preprocessed Information Sources

| Hierarchy Levels | Examples | |

| (Highest-Level Resource) | Systems | Clinical practice guidelines Evidence-based textbook summaries Clinical Evidence (BMJ Publishing Group) |

| ↑ | Synopses of syntheses | Evidence-based abstract journals (e.g., Evidence-Based Nursing) Systematic reviews |

| ↑ | Syntheses | Cochrane Reviews Cochrane Library (www.cochrane.org) |

| ↑ | Synopses of single studies | Evidence-based abstract journals |

| (Lowest-Level Resource) | Single studies | PubMed clinical queries |

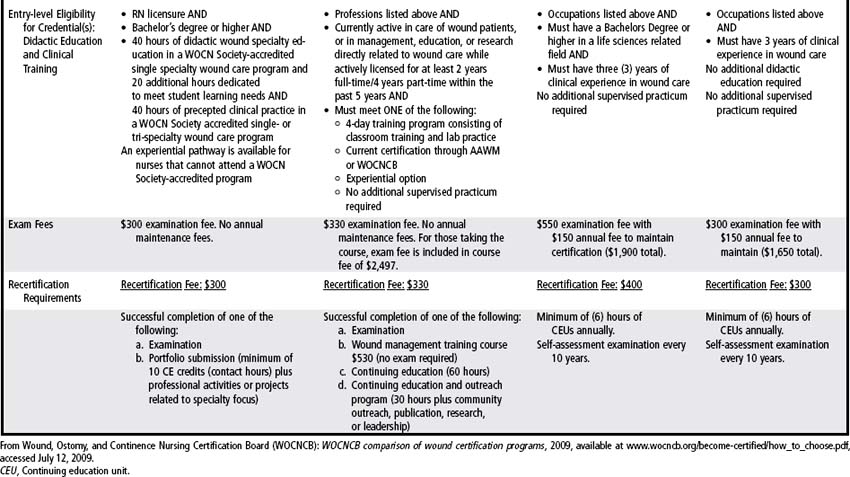

When preprocessed information resources relative to a particular clinical issue are not available, unprocessed resources are necessary. Unprocessed resources are databases (e.g., CINAHL, MEDLINE, EMBASE) that contain millions of primarily original study citations (Table 1-6). The World Wide Web also is an unprocessed resource, although its potential for inaccurate information is substantial. Seven criteria have been developed (Table 1-7) that can be used to assess the quality of health care information obtained from the Internet (AHCPR, 1999; Holloway et al, 2000).

TABLE 1-7 Criteria for Evaluating Internet Health Information

| Criteria | Description |

| Credibility | Includes source, currency, relevance/utility, and editorial review process for the information |

| Content | Must be accurate, complete, and provide an appropriate disclaimer |

| Disclosure | Includes informing the user of the purpose of the site as well as any profiling or collection of information associated with site use |

| Links | Evaluated according to selection, architecture, content, and back-linkages |

| Design | Encompasses accessibility, logical organization (navigability), and internal search capability |

| Interactivity | Includes feedback mechanisms and means for information exchange among users |

| Caveats | Clarifies whether site functions as marketer of products and services or as provider of primary information content |

Data from Agency for Health Care Policy and Research (AHCPR): Assessing the quality of Internet health information, 1999, available at http://www.AHRQ.Gov/Data/Infoqual.htm, accessed July 6, 2009, and Mitretek Systems, McLean, Va.

Because the methodologic quality of studies obtained using unprocessed sources will vary, each study or report will require a critical appraisal to differentiate misleading research reports from valid reports. Many sources that discuss the critical appraisal of research are available (Callihan, 2008; Webb, 2008). However, many providers are not comfortable with their research appraisal skills. To simplify the process, Cullum and Guyatt (2005) propose asking three discrete, sequential questions, as discussed in Table 1-8.

TABLE 1-8 Guide for Evaluating Intervention-based Research

| Steps | Description | Related Study Design Questions |

< div class='tao-gold-member'> Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|