(1)

Department of Orthopedic Surgery ASAN Medical Center, University of Ulsan College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea, Republic of South Korea

Abstract

Once the patient is admitted for the operation, it is necessary to carefully review again whether TKA is really needed and whether the patient’s condition is suitable for undergoing the surgery. The knee joint and general condition must be carefully reassessed through history taking and physical examination on preoperative checkup. If no specific problems are noted during the preoperative checkup, the patients should be educated regarding postoperative care, progress, prognosis, and complications of TKA, and meticulous preparation should be carried out for the operation in order to prevent the occurrence of any incidents or complications perioperatively.

Once the patient is admitted for the operation, it is necessary to carefully review again whether TKA is really needed and whether the patient’s condition is suitable for undergoing the surgery. The knee joint and general condition must be carefully reassessed through history taking and physical examination on preoperative checkup. If no specific problems are noted during the preoperative checkup, the patients should be educated regarding postoperative care, progress, prognosis, and complications of TKA, and meticulous preparation should be carried out for the operation in order to prevent the occurrence of any incidents or complications perioperatively.

3.1 Admission Checkup

3.1.1 History Taking

On admission, it is necessary to carefully assess whether arthroplasty is the only method to relieve the pain and to improve the function, because many items for operation may be missed during the outpatient assessment. Since the intensity of pain is not always the same, the current severity of pain may be different from that at the time when it was decided to perform the TKA. In terms of function, it is necessary to assess the current level of function. Two questions that may help the surgeon to assess the current level of function are, “how much discomfort is the patient feeling due to the loss of function?” and “how much is the motivation to improve the function?”

It is inappropriate to perform TKA not only in those patients who have less pain and functional disturbance but also in those patients whose general condition is very poor. Lavernia et al. reported that the patients with a preoperative WOMAC score more than 51 showed a higher postoperative WOMAC score.

The patient’s past history and current condition of the knee joint should be enquired in detail. In particular, the history of previous knee surgery including the timing and the type of operation performed should be known as it might have altered the anatomy of the knee joint.

It is also very important to assess the condition of spine and hip joints and the vascular status of the lower limb. Elderly patients often experience radiating pain and/or muscle weakness due to spinal problems. In such cases, pain and/or functional disturbance may persist even after arthroplasty, and the patient satisfaction may decrease despite of functional improvement after TKA. Vascular claudication is often masked in the patients with arthritis because of restriction of activity, and hence careful history taking is required. If the vascular status of the lower limb is not normal, it can cause a vague pain, increase the risk of swelling or thrombosis postoperatively, or aggravate arteriosclerosis to cause postoperative circulatory disturbance.

Past medical history should include the history of cardiopulmonary diseases, diabetes mellitus, endocrine diseases, gastrointestinal diseases, and renal diseases. Medical checkup should be done in order to know the patients’ current general condition in case they have a history of any of the above diseases.

The risk of cardiopulmonary complications during the perioperative period of TKA is so high that in case of any doubt, a detailed study should be performed. Since many elderly patients have diabetes mellitus, the surgeon should be aware of the type and method used to control the ailment as well as how it is being controlled currently.

The possibility of iatrogenic Cushing’s syndrome should be excluded if the patient displays features of moon face or generalized body edema. Some patients may have functional disturbance of the thyroid, which they may inform in advance most of the times.

Since infection is the most serious complication of TKA, it is essential to check for the possibility of activation of infection if they had recently undergone tooth extraction, received acupuncture or moxibustion, or suffered from genitourinary infections.

If the patients had undergone any other operation, enquire regarding the name and timing of the operation. If necessary, the surgeon who had performed the operation should be contacted, or a specialist for that particular operation should be consulted in order to determine whether the patient can undergo arthroplasty.

If these procedures are ignored, there may be an unacceptably high risk of morbidity or mortality after TKA which is just an elective surgery to reduce the pain and to improve function.

3.1.2 Physical Examination

First of all, the skin condition should be checked. The yielding behavior or the elasticity of skin are very important for the wound healing and postoperative rehabilitation. If there is a preexisting surgical scar on the knee joint, its location and adhesions with the subcutaneous tissues should be examined by palpation. Information regarding recent skin problems and whether or not acupuncture or moxibustion has been performed is helpful in eliminating the sources of an occult infection.

Also, the presence of a tender point, heat sensation, joint swelling should be checked, and an effusion should be differentiated from a synovial hypertrophy. Patellar compression test is helpful in order to decide whether or not to resurface the patella in selective patellar replacement.

The type and the degree of deformity will affect the selection of implants as well as the operative procedures. Hence, the deformity should be examined carefully. Flexion contracture is well observed when the knee is rested on a flat surface. Flexion contracture should be differentiated from the extension lag in which the knee can be extended passively but cannot be extended actively, since the surgical procedures for flexion contracture and extension lag may be different.

Preoperative evaluation of the knee instability is also important. Mediolateral knee instability as well as A–P knee instability should be assessed preoperatively by physical examination and stress X-ray.

Active and passive ROM should be checked with the use of a goniometer. Lavernia et al. stated that when the ROM is checked by the naked eye, it is overestimated than the real ROM.

One of the most important points to be checked, although it is often skipped, is examining the power of the quadriceps and hamstrings. In particular, the power of the quadriceps is closely related to the prognosis.

The examination of the knee joint is followed by the examination of the spine and hip joints. Although it is obviously important, examination of the vascular system is often overlooked during the physical examination. However, it is critical to examine the vascular system to prevent circulatory compromise postoperatively. When there is a weak pulse, skin ulcers, or toe necrosis, the possibility of vascular disease is very high.

3.1.3 Preoperative Evaluation

Preoperative evaluation can be divided into two sections, general routine checkup and checkup of the knee joint. The routine checkup is a basic examination, and the past medical history or abnormalities found during the routine checkup need to be studied in more detail.

Echocardiogram or thallium scan is necessary when abnormal findings are noted on the EKG. In case of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, endocrine diseases, or disorders of brain or central nervous system, it is recommended to consult a specialist of the respective field so as to perform an appropriate examination, control the ailment, and make a decision regarding the operative risk. In case of osteoporosis, bone densitometry is performed, and treatment can be started postoperatively, if needed.

In cases the patients who have a history of thrombosis or who are at a high risk for DVT, duplex sonography or RI venography may also be performed. If the pulse is weak or calcification along the vessels is seen on the plain X-ray, a Doppler test should be performed, and this can be followed by an angiography if required.

For back pain, radiating pain, or muscle weakness in the lower limb, a plain X-ray as well as MRI or CT of the spine are helpful.

For examining the knee joint, a simple X-ray is the routine, and additional images may be taken according to the knee joint condition. The standing true A–P, lateral X-rays, the axial views, and a scanogram for choosing the appropriate size of the implant are fundamental.

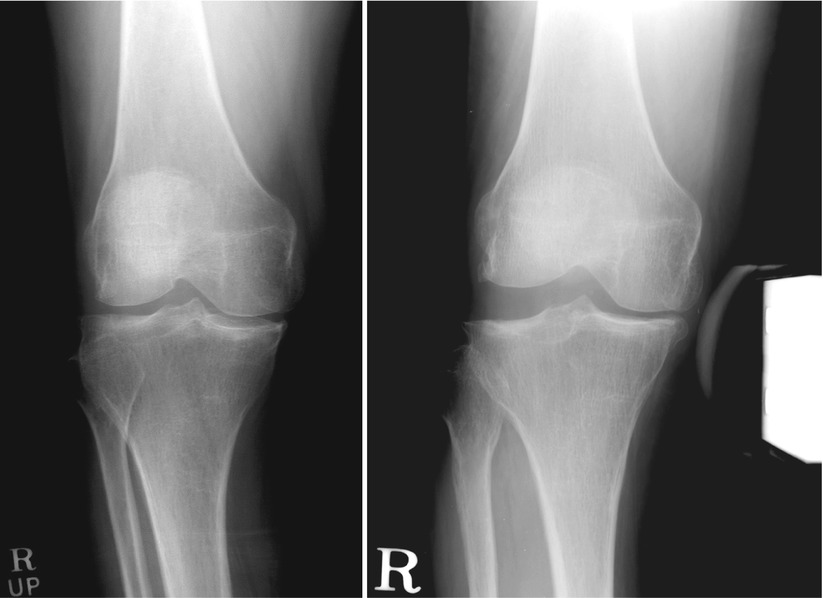

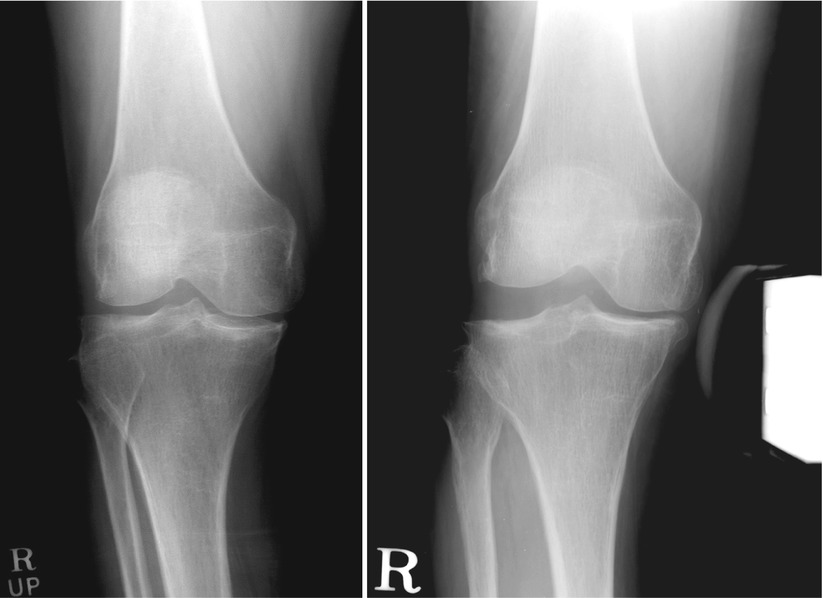

In order to evaluate the tibiofemoral angle in the coronal plane, the A–P X-rays of the whole lower limb must be taken with the patella facing anteriorly. Otherwise, the limb can undergo rotation and an inaccurate angle of the axis may be measured. In case of rotational deformity of the knee, the X-rays must be taken one after another separately to measure the correct angle of axis. Even in the patients without knee instability, taking the valgus and varus stress X-rays is very useful (Fig. 3.1).

Fig. 3.1

The left image shows a weight-bearing standing view, and the right image shows a stress X-ray of the same knee joint. The right image appears more lax on the lateral side than the left image

The MRI of the knee is only necessary to determine the causes of knee pain other than osteoarthritis. Hence, it is not needed in patients in whom the decision of performing an arthroplasty has already been made.

If inflammatory disease is suspected on routine checkup, joint aspiration or WBC bone scan may be helpful.

3.2 Final Decision

After a thorough preoperative checkup, the final decision regarding whether or not to perform the operation should be made. If TKA is not really needed at the moment or there are significant risks associated with TKA operation, it must be either cancelled or postponed.

Once the decision is made to perform TKA, it must be decided whether to perform TKA simultaneously on both the knees (one-stage TKA), or perform TKA on one knee followed by the other knee after a certain time interval (two-stage TKA). This decision is usually made before admission, but the results of preoperative checkup can change the decision.

In case of the one-stage operation, it can save costs and shorten the rehabilitation period. However, the one-stage operation can increase the risks associated with TKA. Hence the age of the patient, general condition, and condition of the knee joint should be taken into account. On the other hand, the two-stage operation prolongs the duration of hospital stay which is a great burden to both the patients and their families.

As for the terminology, concomitant or simultaneous operation indicates that two teams of surgeons perform the operation on one leg each at the same time. In such a case, the duration of anesthesia can be reduced, but it can lead to overburdening of the heart hemodynamically, thereby increasing the risks. Also, it may be inconvenient for the two teams of surgeons to work simultaneously and the risk of infection is elevated. Hence, this operation is only undertaken in exceptional cases at specialized centers. In general, a simultaneous operation means one-stage operation or sequential bilateral operation under one anesthesia. Performing the operation on one knee followed by the other knee after some time interval is called the two-stage or sequential operation under two anesthesias.

It is generally agreed that the results of TKA are not different whether it is done simultaneously on both knees or on one knee followed by the other. The biggest controversial issue is the incidence of complications; the one-stage surgery is generally thought to have greater risks because the operation time is longer, the need for transfusion is increased due to more bleeding, the incidence of congestive heart failure is raised due to a hemodynamic shift, and the incidence of acute delirium is increased due to fat embolism. Restrepo et al. reviewed 27,807 patients through a meta-analysis of 18 literatures and reported that a significantly higher incidence of pulmonary embolism, cardiovascular complications, and mortality was seen in the patients who underwent one-stage operation than that in the patients who underwent two-stage operation. Lynch et al. reported that the patients above 80 years of age showed a higher rate of complications after simultaneous operation compared to that after two-stage operation. They also reported that these complications were related to the preoperative cardiac conditions and the duration of operation.

On the other hand, Kollettis et al., Lewallen, and Hooper et al. reported that the chances of complications were not increased after the simultaneous operation in ordinary patients. Vince et al. reported that it may be true that the simultaneous operation was associated with a higher rate of complications, but this complication rate was still lower than that after the second operation of the two-stage operation. Kim et al. reported that there were no differences in the complications and mortality between one-stage and two-stage operation even in the high-risk patients. Morrey et al. also reported the following rates of complications: 7 % for the two-stage operation performed during the same admission period, 9 % for the simultaneous operation, and 12 % for the two-stage operation performed during two separate admissions. Soudry et al. stated that the incidence of thrombosis rather increases with the two-stage operation. Ritter and Hardy found a higher mortality rate after the simultaneous operation, but the incidence of wound infection was decreased to almost half.

With regard to the time interval between the two operations in the two-stage operation, Foster et al. reported that the bleeding was reduced when the two operations were performed 1 week apart, and Sliva et al. recommended that the two operations should be performed 4–7 days apart during the same admission period. On the other hand, Ritter and Hardy recommended that the two operations should be performed 3–6 months apart since it is the safest and least expensive and is associated with lowest mortality.

Recommended indications for simultaneous operation are when anesthesia is difficult due to rheumatoid arthritis or ankylosing spondylitis in which several operations are required to be performed for other lesions besides the knee joints and the socioeconomic conditions are not favorable. In case of severe deformity (varus–valgus deformity and flexion contracture) of both knee joints, the one-stage operation is recommended as the nonoperated knee may have a negative impact on the operated knee postoperatively. Harato et al. stated that the loading was increased on the operated knee when the opposite limb had a flexion contracture. If the subsequent TKA is done within a shorter interval, it does not cause any problems. But there is always a possibility of delay in the operation on the other knee joint for a long time due to unexpected reasons.

Scott preferred the one-stage operation, and I would like to introduce his method here because it could be a realistic and helpful method. If patients have medical problems or are not willing to undergo the one-stage operation, the two-stage operation is performed. If one knee is less severely affected than the other knee, the patients should be asked whether they want to undergo an operation on the less painful knee assuming that the more severely affected side would be pain-free. If they want to undergo the operation on the less painful knee, the simultaneous operation is performed.

Regional anesthesia, especially epidural anesthesia, is preferred, and warfarin is used as an antithrombotic agent from the night before the operation. Antibiotics are administered thrice: twice before each operation and once after the operation.

The operation should start on the more severely affected knee joint, because it is possible that the operation can be cancelled due to the patient’s condition. Operation on the second knee joint is started after skin closure of the first operated knee joint. New set of surgical instruments should be used, and everyone involved in the first operation should change their gloves. An attempt is made to make a skin incision of the same length.

Postoperative pain control is achieved with patient-controlled analgesia (PCA), and warfarin is administered for 4–6 weeks. Rehabilitation program would be the same as that for the one-stage operation.

In case skin incisions of different lengths are made on the two knee joints and if the patients ask about it, they are told that more things were needed to be done in one knee joint. If the progress of the TKA is different between the two knee joints, the patients are explained that the less affected knee joint is showing much better results than usual.

Author’s Opinion

I think that the one-stage operation has many benefits as it saves costs, shortens the rehabilitation period, and increases the patient satisfaction. In case of the two-stage operation, there is a possibility of cancellation of the operation on the second knee. The nonoperated knee joint can have an adverse effect on the operated knee joint in case there is a deformity, severe instability, or ankylosis. So, the one-stage operation is performed in these cases unless there are special reasons for not doing so.

However, the two-stage operation should be performed if the patients are older than 80 years of age, patient’s general condition is poor, there is a history of cardiac problem, or other risk factors were detected in the preoperative checkup.

I have performed more than 6,000 TKAs based on this principle, and I have not found any significant difference in the complications.

3.3 Outcome Study

Although the evaluation of TKA is done after the operation, its outcome should be compared with the preoperative status of the knee joint. Therefore, the outcome study should start from the preoperative period. This is not only important for the development of arthroplasty, but it is also essential for the surgeon to check the patient’s preoperative condition and the feedback after surgery.

To accomplish this purpose, a long-term follow-up should be done with the most widely used evaluation methods. If this is not done, it is difficult to evaluate the commonly accepted results by the researchers because of the bias arising from the differences in patient selection or regional differences.

No matter which evaluation method is used, it should be applicable to all patients and provide reproducibility and accuracy. In order to achieve these, a well-trained examiner or interviewer is needed, and the patients should be able to understand the survey correctly.

As knee surgeries, especially arthroplasty, have become popular, several evaluation methods have been introduced until now. There are about 40 evaluation methods available currently. There are basically two methods, one is evaluation by the medical personnel or interviewer and the other is evaluation according to the survey or through the recordings by the patients themselves.

The most widely used methods by the medical staff are the Hospital for Special Surgery Knee score (HSS score) and Knee Society score (KSS) which was basically derived from the HSS score. These scores are calculated from the interview or from the examination by a physician or a trained medical staff. There is also a patellar scoring system for evaluating the patellofemoral conditions. These methods are based on the evaluation of pain and function in the knee joints. Hence, the socioeconomic factors, such as income and family relations as well as the psychological factors are excluded.

However, subjective evaluation by the patient is as equally important as the objective evaluation. The results of surgery may be affected by the nonphysical factors such as those mentioned above and the patients’ expectations. The WOMAC score (Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index score) evaluates the patient’s pain and function, and the SF-36 (short form 36) evaluates the patient’s quality of life through the patient survey or recordings by the patients themselves. However, Hamilton et al. suggested that patients’ reporting of functional outcome after TKA is influenced more by their pain level than their ability to accomplish tasks.

The Knee Society Total Knee Arthroplasty Roentgenographic Evaluation System is a radiological method of evaluation.

3.3.1 HSS Score

The HSS Knee Score (Table 3.1) was introduced by the Hospital for Special Surgery (HSS) in the 1970s to evaluate the results of hip and knee joint surgery. It is also used to evaluate the results of other hip and knee surgeries besides arthroplasty and offers different versions for the hip and knee joints. The evaluation is accomplished through the interview and physical examination by the medical personnel or by a well-trained specialist appointed for performing the evaluation.

Table 3.1

The Hospital for Special Surgery scoring system

|

The HSS scoring system comprises of seven basic categories—pain, function, range of motion, muscular strength, flexion deformity, instability, and subtractions—with a total of 100 points. Pain has the largest impact for the score (30 points), followed by function (22 points), range of motion (18 points), muscular strength, flexion deformity, and instability (10 points each). Fifty out of the 100 points are assigned by an interview and the remaining 50 points by the physical examination. Higher scores mean better results.

For a better understanding, the background of the HSS score needs more explanation. Although distance of a block is ambiguous, originally one block means a block in the streets of Manhattan, which is about 1/20 miles (approx. 80–100 m). The walking distance refers to the distance which the patients can walk without taking rest.

In the climbing up and down the stairs item, 5 points are given if the patients can do so without any aid, 2 points if they need some aid such as holding the handrails, and 0 point if they need a lot of help. Transfer receives 5 points if the patients can rise from a chair without any aid, 2 points if they need to grab the armrest, and 0 point if they need a lot of help.

For the range of motion, the maximum range of motion is set at 144° and the angle of motion is divided by 8 and is rounded to the nearest integer (e.g., 0–95° = 11 points).

For muscular strength, the patients are asked to sit and extend the knees. Break refers to bending the legs with the use of the examiner’s force. Therefore, “cannot break quadriceps” means that the examiner cannot bend the patient’s knees with examiner’s applied force.

Instability is measured by the instability found on varus and valgus stress test in full extension or flexion at 90°. If there is instability in flexion or extension, it should be measured.

For subtraction, normal alignment is set at 7° of valgus tibiofemoral angle in full extension, and any angle that exceeds 7° or is less than 7°, either a valgus or varus, 1 point is subtracted per every 5°.

For the overall evaluation, the knee is rated as excellent if the HSS score is between 85 and 100, good if the HSS score is between 70 and 84, fair if the HSS score is between 60 and 69, and poor if the HSS score is below 60.

The advantage of this evaluation method is that it is used worldwide, and hence a comparison can be done between the researchers as well as between the implants according to the time sequence. The drawback of this evaluation method is that examiner’s bias can influence the score, and the score may change according to the patient’s physical condition or age even though the condition of the knee joints is the same. Cho et al. reported that the score could change according to single and bilateral TKA, or other physical and medical conditions. Also, there is a probability of an interobserver and intraobserver bias.

In spite of these drawbacks, the HSS score can provide an objective evaluation of the patient’s physical condition including pain and function of the knee joint. Regarding the interpretation of the HSS score, for example, if the KSS is good and the HSS score is low, it means that the condition of the knee joint is good, but the patient’s physical condition is poor.

3.3.2 Knee Society Score

The Knee Society was organized in 1983 by the surgeons who were interested in knee joint surgery. In 1989, the KSS (Table 3.2 ) was designed to overcome the drawbacks of the HSS score. The KSS added the A–P and mediolateral instability to the HSS, and the patients were divided into three groups based on the associated medical conditions which could affect the evaluation score.

Table 3.2

The Knee Society scoring system

|

The KSS has a different scoring system as compared to the HSS, and it consists of three sections: knee score (100 points), knee function score (100 points), and a patient classification system. This evaluation, like the HSS score, is accomplished through an interview and examination by a surgeon or a trained medical staff.

The knee score is divided into pain, range of motion, and mediolateral and A–P instability with subtractions for flexion contracture, extension lag, and malalignment. The maximum 50 points are assigned to pain. Twenty-five points are given to ROM and stability, respectively. For the evaluation of range of motion, 1 point is added for every 5° to get a full 25 points if it is more than 125°. For the evaluation of stability, 15 points are given for mediolateral stability and 10 points for A–P stability.

In terms of alignment, 5–10° of valgus is considered normal, and any angle exceeding 10° or less than 5° is subtracted from 5 to 10°, and the remainder is multiplied by 3, and then these points are subtracted. For example, if there is 3° of valgus, 3 is subtracted from 5 (as 5–10° of valgus is normal), and the remainder 2 (5–3) is multiplied by 3, and thus 6 (2 × 3) points are subtracted.

The knee function score consists of walking and going up and down the stairs; each item has 50 points. Fifty points are given if there are no limitations on walking, 40 points are given if one can walk more than 10 blocks, 30 points if one can walk 5–10 blocks, 20 points if one can walk less than 5 blocks, 10 points if one can only ambulate within the home, and 0 point if one cannot walk at all. Here, one block refers to 1/20 miles (approx. 80–100 m). For walking the stairs, 50 points are given if there is no problem going up and down the stairs, 40 points when no problem is noted on going up the stairs but one needs to hold the handrails when going down the stairs, 30 points if one needs to hold the handrails when going up and down the stairs, 15 points if one cannot go down the stairs, and 0 point if one cannot go up and down the stairs.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree