Posterior Spinal Fusion for Idiopathic Scoliosis

Peter O. Newton

Vidyadhar V. Upasani

DEFINITION

Idiopathic scoliosis is a progressive three-dimensional spinal deformity in the absence of any congenital spinal anomaly or associated musculoskeletal condition.

Categorized as early onset (before the age of 5 years) or late onset (after the age of 5 years).3

ANATOMY

The spinal deformity is divided into three areas: proximal thoracic, main thoracic, and thoracolumbar/lumbar.

A proximal thoracic curve has an apex between T2 and T5. A main thoracic curve has and apex between T5 and T12 and a thoracolumbar/lumbar curve has an apex between T12 and L4.

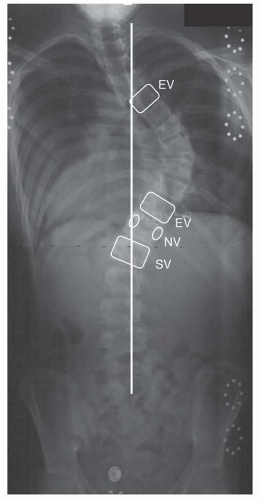

Vertebral definitions (FIG 1)

The end vertebrae define the extent of each curve and are most tilted from horizontal in the coronal plane.

The stable vertebra is defined as the vertebra most closely bisected by the center sacral vertical line (CSVL).

The neutral vertebra is defined as the least rotated vertebra in the axial plane based on the radiographic symmetry of its pedicles.

PATHOGENESIS

Twin studies and observations of familial aggregation reveal significant genetic contributions to deformity progression.1, 13

Increased calmodulin (which regulates the contractile properties of muscles and platelets) and decreased melatonin (a calmodulin antagonist) levels have been found in patients with progressive scoliosis.7, 11

Differential growth rates in the anterior and posterior spinal column may cause imbalance in the sagittal plane with subsequent buckling of the vertebral column.5

NATURAL HISTORY

Risk factors for deformity progression include female gender, greater growth potential, thoracic curve location, and larger curve magnitude.6, 15

Radiographic markers of skeletal maturity (state of the triradiate cartilage, Risser sign, carpal ossification, growth centers around the elbow) can be used to define a patient’s remaining growth potential.

After skeletal maturity, curves less than 30 degrees tend not to progress, whereas curves greater than 50 degrees tend to progress about 1 to 2 degrees per year.19, 21

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

Document medical history, developmental milestones, growth history, and family history.

Observation should assess for asymmetries of the neck, shoulders, ribs, waist, and hips. Cutaneous lesions such as hairy patches or sinuses may suggest spinal dysraphism, whereas café-au-lait spots or axillary freckling may suggest neurofibromatosis.

Adams forward bend test is used to identify a unilateral prominence of the thoracic rib cage or lumbar paraspinal muscles due to axial rotation of the spine.

Coronal decompensation can be identified as lateral translation of the C7 spinous process in relation to the gluteal cleft.

Clinical assessment of maturity based on Tanner stage. Peak growth velocity occurs approximately 6 to 12 months prior to the onset of menses in girls and the onset of axillary and facial hair in boys.17

Assessment of functional capacity is performed by analyzing gait, stance, motor and sensory function, and reflexes.

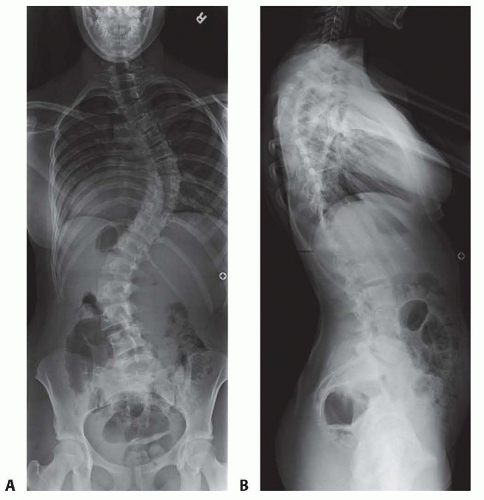

FIG 2 • Posteroanterior (A) and lateral (B) radiographs demonstrating a typical right thoracic deformity with apical lordosis. (©SD PedsOrtho.)

Abdominal reflexes should be assessed to rule out intramedullary lesions. Unilateral absence of the reflex suggests the need for a spine magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

Limb length discrepancy can result in apparent scoliosis.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Full-length, upright posteroanterior (FIG 2A), and lateral (FIG 2B) spinal radiographs are adequate for routine assessment.

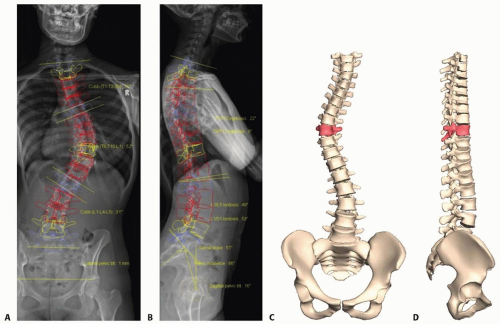

Three-dimensional reconstructions using advanced, low-radiation imaging technology can provide important insights into the true scoliotic deformity (FIG 3).4

Lateral bending radiographs are important for preoperative planning to determine curve flexibility but are not required otherwise.

Advanced imaging studies including computed tomography and MRI can be used to identify neurologic or congenital abnormalities.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Congenital scoliosis (failure of vertebral formation or segmentation)

Neuromuscular scoliosis (cerebral palsy, spinal muscular atrophy, Duchenne muscular dystrophy)

Syndromic scoliosis (osteochondrodystrophies, neurofibromatosis, Marfan syndrome)

NONOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

Periodic observational monitoring is appropriate for skeletally immature patients with curves between 11 and 25 degrees. During periods of peak growth, more frequent evaluations (every 4 to 6 months) should be performed.

Skeletally immature patients (less than Risser 2) with documented curve progression to greater than 25 degrees or 30 degrees on initial presentation can be treated with a rigid thoracolumbosacral orthosis.2

Bracing has been shown to successfully decrease the progression of high-risk curves during the adolescent growth spurt. A dose-dependent relationship between hours of brace wear and success with bracing has been identified.16, 20

A coordinated effort between the patient, the treating physician, and the orthotist is required to optimize success with bracing.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Surgical goals are as follows:

Obtain three-dimensional and well-balanced deformity correction while fusing as few motion segments as possible.

Obtain a solid arthrodesis to prevent deformity progression.