Fig. 10.1

(a) Anteroposterior (Grashey view) and (b) axillary radiographs demonstrating a posterior shoulder dislocation. Note the positive “lightbulb sign” and “empty glenoid sign” on the Grashey view

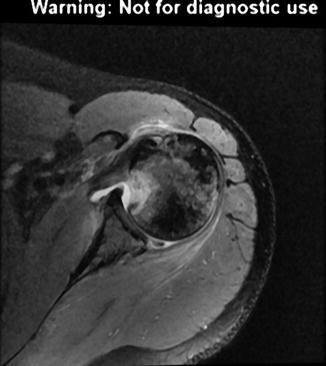

Fig. 10.2

Axial T2-weighted shoulder MRI demonstrating sequelae of prior posterior shoulder dislocation: posterior labral tear, posterior glenoid bone defect, and reverse Hill-Sachs lesion

Treatment Considerations

Nonoperative treatment should be considered in most cases of posterior shoulder instability. Conservative treatment consists of physical therapy to regain full and symmetric shoulder range of motion, with subsequent emphasis on strengthening of the rotator cuff and the scapular stabilizing muscles. Strengthening the dynamic stabilizers of the glenohumeral joint, such as the rotator cuff and the periscapular musculature, may permit compensation for deficient static stabilizers, such as the labrum and the capsule. If nonoperative treatment is successful in restoring full range of motion without recurrent instability, gradual return to sport may be initiated.

Surgical treatment of posterior instability is indicated when conservative management fails to alleviate pain or prevent recurrent instability. Historically, these patients were treated with open posterior stabilization procedures. These techniques had high recurrence rates (as high as 40 %), and few patients treated with these open procedures returned to their previous and desired level of activity [5, 8, 9, 11–14]. With the advent of advanced arthroscopic techniques, the mean recurrence rate following surgical treatment for posterior shoulder instability has decreased to 5 %, with a range of 0–10 % in most recent series. Furthermore, a greater percentage of patients have returned to their previous level of activity or sport (89–100 %) [15–17]. When comparing open versus arthroscopic stabilization procedures, the latter has been shown to result in superior functional outcomes [18]. Arthroscopic procedures are generally more successful because they are more effective at restoring native anatomy. Cadaver biomechanics studies have shown that open bone block procedures, which involve creating a buttress against posterior humeral translation, over-constrain the joint and do not restore inferior stability as effectively as arthroscopic posterior Bankart repairs [19].

Arthroscopic Technique for Posterior Instability

In the majority of patients with posterior shoulder instability, arthroscopic surgery can result in excellent functional outcomes with low rates of recurrence and complications. The authors’ preferred technique is described below.

Prior to surgical intervention, patient history, physical examination, and imaging studies should be reviewed. Concomitant pathology, such as rotator cuff tears, SLAP tears, bone defects, and loose bodies, should be identified in advance. General anesthesia with an interscalene block is most effective at achieving complete muscle relaxation. Prior to positioning, an examination under anesthesia is performed to confirm the diagnosis and to assess the degree of instability. The examination may include the sulcus test, load-and-shift test, jerk test, Kim test, and/or circumduction test. We prefer lateral decubitus positioning as it allows greater exposure of the posterior labrum and capsule when compared to beach-chair positioning. An inflatable beanbag should be utilized to restrain the patient, with appropriate cushioning of the axilla and bony prominences. The operative extremity is placed in balanced arm traction in 45° of abduction and 20° of forward flexion using 10–15 pounds of weight.

We prefer an all-arthroscopic repair technique. A single posterior portal in line with the lateral edge of the acromion and through the deltoid is created first. This portal is utilized for anchor placement and suture management. It should permit an anchor placement trajectory of 45° relative to the glenoid face. Placement of this portal slightly lateral to the standard posterior portal may allow superior access to the posterior glenoid rim for lateral anchor placement. Alternatively, if the anchor placement trajectory is less than ideal through the posterior portal, an accessory lateral portal may provide better access, particularly to the 7-o’clock position of the glenoid margin. The anterior portal is then created through the rotator interval just inferior to the biceps tendon via either an inside-out technique with a switching stick or an outside-in technique with a spinal needle. Clear cannulas are placed through both portals: a 5.75-mm cannula anteriorly for arthroscopic visualization and an 8.25-mm cannula posteriorly for the working portal.

With the arthroscope in the posterior portal, a diagnostic arthroscopy is performed. The articular surfaces of the glenohumeral joint are inspected for chondral damage, the humeral head is evaluated for Hill-Sachs lesions, and the glenoid rim is assessed for bone defects. The anterior and inferior labrum and the glenohumeral ligaments are visualized and inspected. The biceps tendon and superior labrum should be probed through the anterior portal to detect concomitant pathology, such as a SLAP tear. Finally, the rotator cuff should be inspected, including the subscapularis tendon. The arthroscope is then placed into the anterior portal where it remains for the rest of the operation. Through the anterior portal, the posterior labrum and capsule are inspected and probed. In addition, the anterior humeral head is evaluated for a reverse Hill-Sachs lesion.

Following a thorough diagnostic arthroscopy, a periosteal elevator is used to elevate the labrum off the posterior glenoid rim. Alternatively, the labrum may be mobilized with an arthroscopic rasp or chisel. The posterior margin of the glenoid is then débrided using a motorized burr or shaver device. The elevator, rasp, chisel, burr, and/or shaver may be introduced through an accessory anterior portal for ease of access.

Once the labrum has been elevated and the glenoid rim débrided, the arthroscope remains in the anterior portal. A 70° arthroscope may provide superior visualization of the posterior and inferior glenoid margins. Using the posterior portal as the working portal, anchors are placed along the posterior glenoid margin, starting inferiorly and progressing superiorly as needed (Fig. 10.3). Alternatively, anchors may be placed through small stab incisions if the posterior portal does not afford sufficient access to the glenoid. We recommend biocomposite anchors with a 2- to 2.4-mm diameter, spaced 3–5 mm apart, so as to avoid fragmentation or fracture of the posterior glenoid (Fig. 10.4). The anchor pilot holes are predrilled, and the anchor is inserted with a mallet. The anchors should be placed such that the sutures are perpendicular to the glenoid rim.

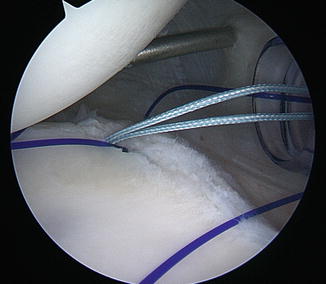

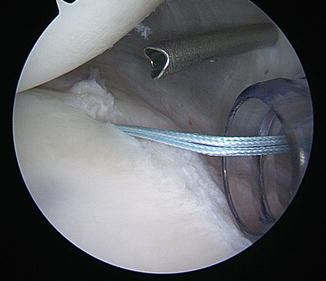

Fig. 10.3

Arthroscopic photograph demonstrating placement of the first anchor along the posterior glenoid margin

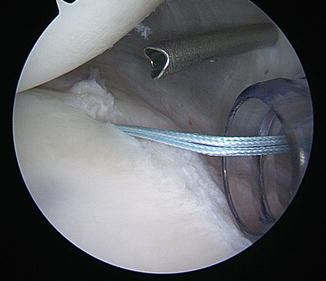

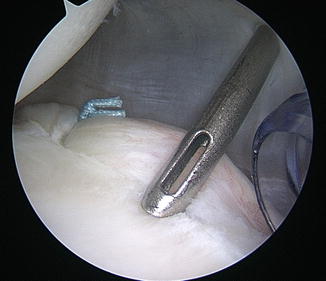

Fig. 10.4

Arthroscopic photograph demonstrating typical anchor spacing (3–5 mm) so as to avoid fragmentation or fracture of the posterior glenoid

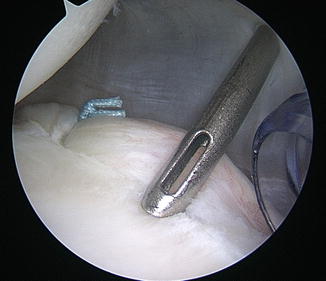

Next, the posterior suture limb of the inferior-most anchor is shuttled around the labrum and capsule (Fig. 10.5). In order to achieve capsular plication, the capsular bite should extend inferior and lateral to the anchor. The direction of suture passage is aimed at restoring tension to the posterior band of the inferior glenohumeral ligament. Patients with significant posterior instability may require a more aggressive plication than those with isolated pathology to the glenoid labrum. Capsular plication should be avoided in high-level throwing athletes who would be impaired by excessive tightening of the posterior capsule: in these cases, the suture can be shuttled around the labrum at the location of anchor placement. Suture passage may be achieved with a suture hook, taking care not to cross the suture. The two limbs of the suture are then tied: the limb that has been passed through the capsule and the labrum should be used as the post limb so as to ensure that the knot is placed away from the glenohumeral joint. The suture limbs of the remaining anchors are then tied in an inferior to superior direction (Fig. 10.6). The tension achieved with each advancing stitch should be assessed. For labral tears that extend to the superior margin of the labrum, care must be taken to avoid abrasion of the knot against the posterosuperior rotator cuff during shoulder motion. To accomplish this, we prefer using either 2-mm anchors loaded with No. 1 suture or a knotless 2.9-mm anchor (Fig. 10.7).