Posterior Cruciate Ligament Surgery

Amanda L. Weller

Craig S. Mauro

Christopher D. Harner

DEFINITION

The posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) serves as the primary restraint to posterior translation of the tibia relative to the femur.

PCL injuries are uncommon, may be partial or complete, and rarely occur in isolation.

Our understanding of the PCL with respect to its natural history, surgical indications and technique, and postoperative rehabilitation is improving rapidly.

ANATOMY

The PCL has a broad femoral origin in a semicircular pattern on the medial femoral condyle.

It inserts on the posterior aspect of the tibia, in a depression between the medial and lateral tibial plateaus, 1.0 to 1.5 cm below the joint line.

Its cross-section area is 11 mm2 on average, which is variable along its course; the average length is 32 to 38 mm.24

Anatomic studies have delineated separate characteristics of the anterolateral (AL) and posteromedial (PM) bundles within the PCL.

The AL bundle origin is more anterior on the intercondylar surface of the medial femoral condyle, and the insertion is more lateral on the tibia, relative to the PM bundle.

The larger AL bundle has increased tension in flexion, whereas the PM bundle becomes more taut in extension.

The meniscofemoral ligaments, which arise from the posterior horn of the lateral meniscus and insert on the posterolateral aspect of the medial femoral condyle, also contribute to the overall strength of the PCL.

PATHOGENESIS

Acutely, there usually is a history of a direct blow to the anterior lower leg. Common mechanisms include high-energy trauma and athletic injuries.

In motor vehicle trauma, the “dashboard injury” occurs when the proximal tibia strikes the dashboard, causing a posteriorly directed force to the proximal tibia.

Athletic injuries usually involve a direct blow to the anterior tibia or a fall onto a flexed knee with the foot in plantar flexion.

Hyperextension injuries, which often are combined with varus or valgus forces, often result in combined ligamentous injuries.

NATURAL HISTORY

There is little conclusive clinical information regarding the natural history of patients with PCL tears treated nonoperatively.

Some studies suggest that patients with isolated grade I to II PCL injuries usually have good subjective results, but few achieve good functional results.17,21,23

A high incidence of degeneration, primarily involving the medial femoral condyle and patellofemoral joint, has been noted in patients treated nonoperatively. This finding is especially prevalent in those patients with grade III injuries or combined ligamentous injuries.

Consequently, pain rather than instability may be the patient’s primary symptom following a PCL injury treated nonoperatively.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

The initial history should focus on the mechanism of injury, its severity, and associated injuries.

With acute injuries, the patient often does not report feeling a “pop” or “tear,” as often is described with anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injuries.

The history also should focus on assessing the chronicity of the injury and the instability and pain experienced by the patient.

A complete knee examination, including inspection, palpation, range-of-motion (ROM) testing, neurovascular examination, and special tests, should be performed.

Posterior drawer test: The most accurate clinical test for PCL injury.

Posterior sag (Godfrey) test: A positive result is an abnormal posterior sag of the tibia relative to the femur from the force of gravity. This result suggests PCL insufficiency if it is abnormal compared to the contralateral side.

Quadriceps active test: useful in patients with combined instability. A posteriorly subluxed tibia that reduces anteriorly is a positive result.

Reverse pivot shift test: A palpable reduction of the tibia occurring at 20 to 30 degrees indicates a positive result. The contralateral knee must be examined because a positive test may be a normal finding in some patients.

Dial test: A positive test is indicated by asymmetry in external rotation. Asymmetry of more than 10 degrees at 30 degrees rotation indicates an isolated posterolateral corner (PLC) injury, whereas asymmetry at 30 and 90 degrees suggests a combined PCL and PLC injury.

Posterolateral external rotation test: Increased external rotation of the tibia is a positive result. Increased posterior translation and external rotation at 90 degrees indicate a PLC or PCL injury, whereas subluxation at 30 degrees is consistent with an isolated PLC injury.

It is important to assess the neurovascular status of the injured limb, especially if there is a history of a knee dislocation.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

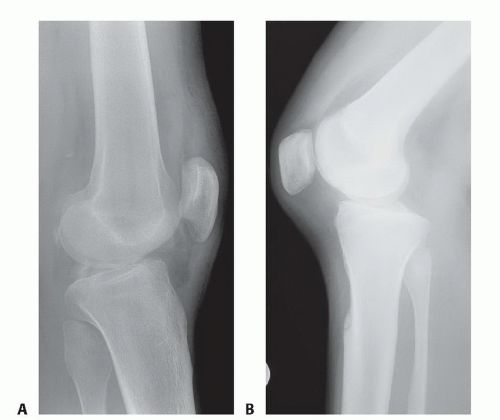

Radiographs of the knee should be performed following an acute injury to assess for a fracture. An avulsion of the tibial insertion of the PCL may be identified on a lateral radiograph (FIG 1A).

In the chronic setting, radiographs may identify posterior tibial subluxation (FIG 1B) or medial and patellofemoral compartmental arthrosis.

Stress radiographs may be used to confirm and quantify dynamic posterior tibial subluxation.12

Long cassette films should be obtained if coronal malalignment is suspected.

MRI is important to confirm a PCL injury, determine its location and completeness, and assess for concomitant injury, including meniscal and PLC pathology.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Combined ligament injury

PLC injury

ACL tear

Tibial plateau fracture

Articular cartilage injury

Medial or lateral collateral ligament tear

Meniscal tear

Patellar or quadriceps tendon rupture

Patellofemoral dislocation

NONOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

Most experts advocate nonoperative management of isolated, partial PCL injuries (grades I and II).15

In these cases, we recommend immobilization in full extension with protected weight bearing for 2 weeks. The goal is to protect the healing PCL/PLC.

ROM exercises are advanced as tolerated, and strengthening is focused on the quadriceps muscles.

Closed-chain exercises (foot on the ground) are recommended.

Applying an axial load across the knee causes anterior translation of the tibia because of the sagittal slope.4 This important biomechanical principle allows early ROM exercises and protects PCL/PLC healing.

The patient usually can return to athletic activities after isolated grade I and II PCL injuries in 4 to 6 weeks. It is important to protect the knee from injury during this time to prevent progression to a grade III injury.

Functional bracing is of little benefit after return to sports activities.

Isolated grade III injuries are more controversial, and nonoperative management may be appropriate in certain patients.

We recommend immobilization in full extension for 4 weeks to prevent posterior tibial subluxation. Weight bearing is protected for the first 2 weeks, then slowly advanced.

Quadriceps strengthening such as quadriceps sets and straight-leg raises is encouraged; hamstring loading is prohibited until later in the rehabilitation course.

During the bracing period, the patient can participate in closed-chain mini-squat exercises which do not stress the PCL or interfere with healing.

After 1 month, ROM, full weight bearing, and progression to functional activities are instituted.

Return to sports usually is delayed for 2 to 4 months in patients with grade III injuries.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Surgical indications include those patients with displaced bony avulsions, acute grade III injuries with concomitant ligamentous injuries, and chronic grade II to III injuries with symptoms of instability or pain.

With any PCL injury, it is imperative to assess the PLC to rule out injury because surgery is indicated for combined injuries.

In higher level athletes, surgical treatment may be considered for acute isolated grade III PCL injuries.

The timing of PCL reconstruction depends on the severity of the injury and the associated, concomitant ligamentous injuries.

Displaced bony avulsions and knees with multiligamentous injuries should be addressed within the first 3 weeks to provide the best opportunity for anatomic repair.6

A number of graft options are available for PCL reconstruction.

Autologous tissue options include bone-patellar tendon-bone, hamstring tendons, and quadriceps tendons.

Allograft options include tibialis anterior tendon, Achilles tendon, bone-patellar tendon-bone, and quadriceps tendon.

Advantages of allograft tissue include decreased surgical time and no harvest site morbidity. Disadvantages include the possibility of disease transmission. The operating surgeon should discuss these issues with the patient preoperatively.

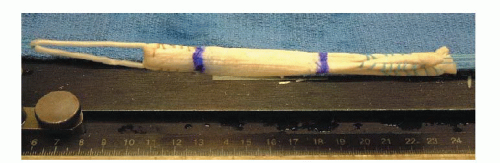

Currently, allograft tibialis anterior tendon is our graft of choice for single- and double-bundle PCL reconstructions (FIG 2).

Preoperative Planning

In the office setting, the surgeon should have a variety of options available and explain that the final surgical plan will depend on the examination under anesthesia (EUA) and the diagnostic arthroscopy.

In the preoperative holding area, sciatic and femoral nerve block catheters may be placed by the anesthesiology staff.

No anesthetic is introduced, however, until neurologic assessment has been completed.

After anesthesia induction in the operating room, an EUA is performed on both the nonoperative and the operative knees.

A detailed examination is performed to determine the direction and degree of laxity.

Data from the contralateral knee may be particularly helpful with combined injuries.

Fluoroscopy may be used after the EUA to assess posterior tibial displacement.

Positioning

The patient is positioned supine on the operating room table.

We do not use a tourniquet.

Depending on the anticipated length of the planned procedure, a Foley catheter may be used.

A padded bump is taped to the operating room table to hold the knee flexed to 90 degrees. A side post is placed on the operative side just distal to the greater trochanter to support the proximal leg with the knee in flexion (FIG 3A). Padded cushions are placed under the nonoperative leg.

For the inlay technique, a gel pad bump is placed under the contralateral hip to facilitate later exposure to the posteromedial knee of the operative extremity in the figure-4 position.

After prepping and draping the operative site, a hole is cut in the stockinette for access to the dorsalis pedis pulse throughout the case (FIG 3B).

Approach

Several techniques have been described for PCL reconstruction. We have developed the following treatment algorithm:

For acute injuries, we employ the single-bundle technique.

If some component of the native PCL remains, we spare this tissue and use the augmentation technique.

This technique can be time-consuming and difficult, but preservation of PCL tissue may provide enhanced posterior stability of the knee and may promote graft healing.

We most commonly perform the double-bundle technique in the chronic setting, when any remaining structures are significantly incompetent.

Some authors advocate the tibial inlay technique for all settings. We typically do not use this technique but have included a description of an open double-bundle technique here as part of a comprehensive overview. All arthroscopic tibial inlay techniques also have recently been described.8,13 A description of the arthroscopic inlay technique is also included.

In cases of displaced tibial avulsion, we use the technique described in the Techniques box.

TECHNIQUES

▪ Single-Bundle Technique

Diagnostic Arthroscopy

A bump is placed between the post and the leg to stabilize the knee in a flexed position while the foot rests on the prepositioned sandbag.

The knee is flexed to 90 degrees, and the vertical arthroscopy portals are delineated.

The anterolateral portal is placed just lateral to the lateral border of the patellar tendon and adjacent to the inferior pole of the patella.

The anteromedial portal is positioned 1 cm medial to the medial border of the superior aspect of the patellar tendon.

Diagnostic arthroscopy is conducted to determine the extent of injury and evaluate for other cartilage or meniscal derangements.

The notch is examined for any remaining intact PCL fibers. If augmentation is to be performed, care should be taken to preserve these fibers (see Single-Bundle Augmentation Technique).

Using an arthroscopic electrocautery device and shaver, overlying synovium and ruptured PCL fibers are débrided, and the superior interval between the ACL and PCL is defined.

An accessory posteromedial portal is created just proximal to the joint line and posterior to the medial collateral ligament (MCL).

A 70-degree arthroscope is placed between the PCL remnants and the medial femoral condyle to assess the posterior horn of the medial meniscus and to localize the posteromedial portal with a spinal needle (TECH FIG 1).

A switching stick can be placed into the posteromedial portal to facilitate exchange of the arthroscope. The 30-degree arthroscope is used when viewing via the posteromedial portal.

Preparation and Exposure of the Tibia

Correct preparation and exposure of the tibia is essential for drilling the tunnel safely in the appropriate position.

TECH FIG 1 • The posteromedial portal is established under direct visualization using a spinal needle.

First, the 70-degree arthroscope is placed into the anterolateral portal, and a commercially available PCL curette is introduced through the anteromedial portal.

A lateral fluoroscopic image can be obtained to confirm its position.

The 30-degree arthroscope is then introduced through the posteromedial portal. The soft tissue on the posterior aspect of the tibia is carefully elevated centrally and slightly laterally.

A shaver can be placed through the anterolateral portal to débride some of the surrounding synovium.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree