Posterior Cruciate Ligament Retention Versus Substitution

The controversy over whether to retain or substitute for the posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) has been ongoing since the advent of condylar total knee arthroplasty (TKA) in the early 1970s. Three schools exist. One almost exclusively preserves the PCL, the second exclusively substitutes for it, and the third is selective. Boston is considered the school of PCL retention, whereas the New York school is one of substitution. In 1974, when I was chief resident in orthopedic surgery at Massachusetts General Hospital, two surgeons from New York, Drs. Chit Ranawat and Peter Walker, came to Boston to share their latest designs of condylar knee prostheses. Both were at the Hospital for Special Surgery at that time and collaborated with Dr. J. Insall on early knee prosthetic designs. A meeting was held in the Smith-Petersen room, and notable attendees included William Jones, Chief of the Knee Service, and William Harris, Chief of the Hip Service. We were shown two options. One was the total condylar prosthesis, which sacrificed the PCL, and the other was the duopatellar prosthesis, which preserved it. The total condylar had a dished sagittal topography, and the duopatellar prosthesis was flat. With the PCL retained and functioning, this flat topography allowed the femur to roll back on the tibia and enhance potential flexion (Figure 1-1). Users of the total condylar technique were reporting average flexion of approximately 85 degrees, and duopatellar users were often achieving more than 100 degrees of flexion. These findings were shared with surgeons at Brigham Hospital, where 85% of patients undergoing TKA at that time had rheumatoid arthritis. Because patients with rheumatoid arthritis often have significant involvement of the upper extremities, the potential for enhanced flexion by retention of the PCL was very attractive. Unless patients achieved well over 100 degrees of knee flexion, they would have difficulty rising from a chair and negotiating stairs and would depend on their upper extremities for these activities. The cruciate-preserving technique therefore was adapted in Boston to better serve the rheumatoid population.1 Nearly all Boston orthopedic residents and fellows were trained in this technique, whereas in New York the practice of sacrificing the PCL predominated. This led to a friendly rivalry between the Boston and New York camps and spawned many formal and informal debates that have continued for decades. In the United States in the 1980s and 1990s, the ratio of retaining to sacrificing the PCL was 60 : 40 in favor of retention. By 2010, this ratio had slowly reversed and has remained constant at 60 : 40 in favor of PCL substitution.

Advantages of Posterior Cruciate Ligament Retention

The potential advantages of preserving the PCL are many. Because stability is imparted by a biologic structure, the prosthesis can be less constrained, and therefore less force is imparted to the insert–tray interface and the prosthesis-to–cement or bone interface. Until cruciate-substituting designs that mandated rollback by their sagittal topography became available, cruciate-retaining knees could achieve a greater potential range of motion than cruciate-sacrificing knees.

With PCL retention, it is also possible to preserve the joint line at a near-normal location. When the PCL is cut, the flexion gap increases and requires a thicker polyethylene for any given amount of bone resection. This thicker polyethylene in turn requires greater distal femoral resection to allow full extension of the knee. Thus the joint line is elevated in both flexion and extension by several millimeters with cruciate-sacrificing designs. This means a mandatory distortion of the collateral ligament kinematics. Although it is possible to equalize the 90-degree flexion gap with the full extension gap, midflexion laxity is bound to occur to some extent when the joint line is elevated. Finally, cruciate-retaining knees allow for preservation of intercondylar bone stock for future revision, if it becomes necessary.

Candidates for Posterior Cruciate Ligament Retention

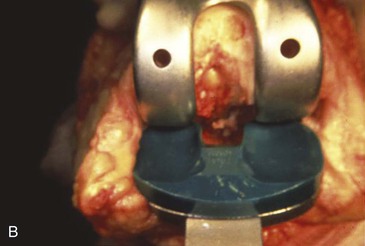

In my experience, the position that knees with severe deformity require PCL sacrifice and substitution is a misconception. I think that at least 98% of primary knees can be treated with PCL retention. This is because the PCL does not have to be “normal” to be retained. In knees with severe varus deformity, the PCL often is encased by intercondylar osteophytes, which must be débrided to define the ligament origin (Figure 1-2). When medial structures are subsequently released (see Chapter 4) to balance lax lateral structures, the PCL indeed is usually too tight relative to these structures and must be released to some extent to balance the knee.

In severe valgus deformity, it is not only possible to preserve the PCL, but it may be preferred because of the medial stabilizing force of this ligament (see Chapter 5). Again, as in severe varus deformity, the ligament often has to be released after the tight lateral side is released to balance the lax medial side (Figure 1-3).

Balancing the Posterior Cruciate Ligament

Another misconception is that balancing the PCL is a difficult and complicated maneuver. Balancing the PCL essentially means leaving the knee with a PCL that is neither too loose nor too tight.

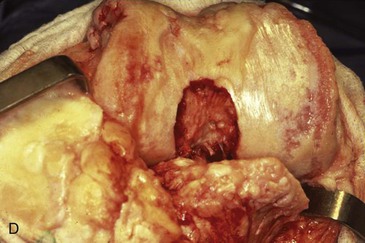

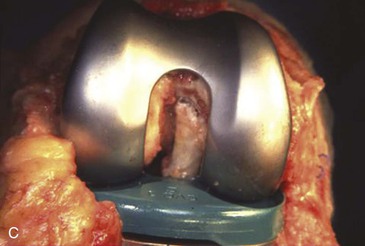

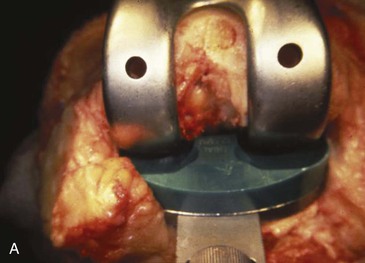

I have developed two simple intraoperative tests for PCL balancing that allow the surgeon to adequately assess these two possibilities and remedy either problem in both fixed-bearing and mobile-bearing knees. The procedure for a mobile-bearing TKA is described in Chapter 2. The procedure for a fixed-bearing TKA is called the pull-out lift-off (POLO) test.2 The pull-out test is to assess the knee for flexion laxity. With the trial components in place (the tibial component must always be placed before the femoral component), the knee is flexed 90 degrees. The surgeon then tries to pull out the tibial component from underneath the femur (Figure 1-4). This test must be performed with an insert that has a curved sagittal topography. The one I use has a posterior lip that is approximately 3.5 mm higher than the midpoint of the articulation. In essence, the pull-out test is to determine whether at least 3.5 mm of laxity or distraction is possible in the flexion gap. Obviously, gradations exist between 1 mm and 3.5 mm of laxity or distraction capability in this test. I prefer the flexion gap to be on the tighter side of this spectrum. A corollary of the pull-out test is the push-in test. In this case, the surgeon pushes the tibial component into place underneath the femoral component, which has been previously inserted. If this is possible in a cruciate-retaining knee, my opinion is that the knee is too loose in flexion, unless the surgeon is using a flat sagittal topography. If the knee fails the pull-out test, thicker inserts are tried until pull-out no longer is possible.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree