Posterior Cervical Fusion with Lateral Mass Screws

Jonathan H. Phillips

Lindsay Crawford

DEFINITION

The lateral mass is a quadrangular area of bone lateral to the lamina and between borders of superior and inferior facets as seen from posteriorly. Seen in three dimensions, the lateral mass is a skewed box. Its appearance on lateral radiographic projection is that of a parallelogram whose anterosuperior corner points cephalad (FIG 1).

Roy-Camille first described the use of lateral mass screw fixation for cervical spine stabilization. Posterior cervical fusion with rigid constructs provides better deformity correction and stability for arthrodesis.

Cervical instability and/or deformity are indications for posterior cervical arthrodesis in the pediatric population.

ANATOMY

Each segment from C3 to C7 is made up of a centrum (body) and two posterior arches that form from mesenchymal tissue migrating around each side of the neural tub.

The arches fuse posteriorly by age 2 or 3 years, and they fuse to the body between 3 and 6 years.

Secondary ossification centers for the superior and inferior ring apophyses ossify during late childhood and fuse to the vertebral bodies by 25 years of age.

Other ossification centers for the transverse and spinous processes generally fuse by 3 years of age.

The facet joints initially are relatively horizontal and, during growth, gradually become more vertical, which enhances stability in flexion and extension. The vertebral bodies initially have an oval or wedge shape but gradually become fully ossified in a more rectangular configuration.4 The spinal nerve exits the canal through the interpedicular foramen. The ventral ramus travels anterolaterally on the transverse process. The spinal nerve sits anteromedial to the anterior aspect of the superior facet. The dorsal ramus runs posteriorly against the anterolateral corner of the base of the superior articular process. When the lateral mass is divided into quadrants, the superolateral quadrant is away from the spinal nerve.

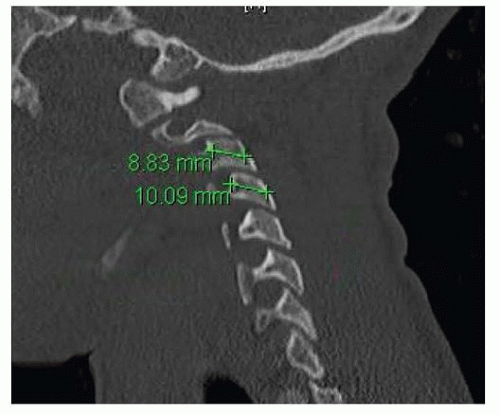

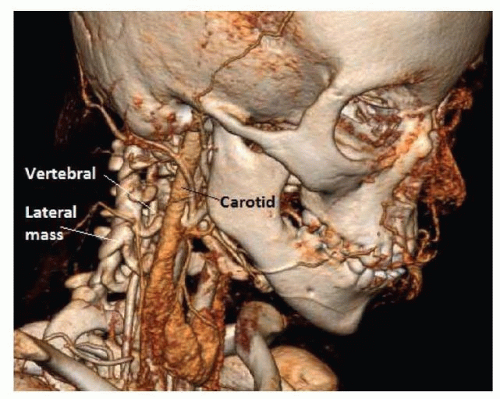

The vertebral artery enters the transverse foramen of the sixth cervical vertebra and courses cephalad through the foramina. The vertebral artery is anterior to the lateral mass but is also anterior to the spinal nerve (FIG 2).

A study by Al-Shamy et al1 of computed tomography (CT) scans of the pediatric cervical spine found that in children age 4 years and older, the size of the lateral mass would allow for lateral mass screw fixation from C3 to C7.

PATHOGENESIS

Trauma

Although spine injuries are rare in children, cervical spine injuries are the majority of spine injuries in children.

Children younger than 10 years of age are more likely to sustain upper cervical injuries (occiput to C2), whereas older children have a preponderance of lower cervical injuries (maximally at C4 or C5).

Tumor: Aneurysmal bone cyst, osteoblastoma, and osteochondroma involving posterior elements are the tumors most likely to be encountered in the first and second decades of life.

Iatrogenic: posterior instability after tumor decompression or postlaminectomy

FIG 2 • Preoperative CT angiogram of an 11-year-old girl with Down syndrome and paraparesis due to C1-C2 instability. Note the relationship of the vertebral artery to the lateral masses.

FIG 3 • Lateral radiograph of an 11-year-old boy with neurofibromatosis. Despite the extent of the kyphosis, he was neurologically intact except for lower extremity hyperreflexia.

Congenital/syndromic: Anomalous cervical spine anatomy can be seen with VACTERL (vertebral, anal atresia, cardiac, tracheoesophageal fistula, renal anomalies, and limb defects) and Klippel-Feil syndrome.

Cervical kyphosis

This can be posttraumatic, postlaminectomy (tumor decompression), or syndromic.

Congenital or developmental cervical kyphosis is associated with Larsen syndrome, diastrophic dysplasia, chondrodysplasia punctata (Conradi syndrome), camptomelic dysplasia, and neurofibromatosis (FIG 3).

NATURAL HISTORY

Instability of the subaxial spine can present with or develop myelopathy.

There is risk of progressive neurologic symptoms and/or progressive deformity of the cervical spine.

Paralysis or death are rare but may occur.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

A thorough history for traumatic injury, conditions that are associated with cervical instability, or history of posterior cervical surgery

Patients may present with complaints of neck pain or decreased range of motion. Patients may have neurologic symptoms on presentation, which may be radicular in nature from cervical nerve root compression or myelopathic from spinal cord compression.

Examination should include a thorough neurologic evaluation including motor and sensory examinations and assessment for myelopathy (hyperreflexia, clonus, pathologic reflexes).

Assess for possible associated abnormalities including a cardiac examination (for congenital/syndromic etiologies).

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Standard radiographs including anteroposterior (AP) and lateral views in neutral, flexion, and extension. An open mouth view should also be taken to ensure that concomitant O/C1/C2 instability is not present.

Lateral views allow for assessment of true instability from pseudosubluxation, which occurs most commonly between the second and third cervical vertebrae and between the third and fourth cervical vertebrae.

The spinolaminar line of Swischuk is helpful to differentiate between pseudosubluxation and true subluxation. This line is drawn along the posterior arch from the first cervical vertebra to the third. It should pass within 1.5 mm of the anterior cortex of the posterior arch of the second cervical vertebra during forward flexion. As long as Swischuk line is maintained, as much as 4 mm of vertebral body subluxation can be accepted.

Fine-cut CT scan of the cervical spine to assess for anomalies of the cervical anatomy including location of the vertebral artery and for preoperative planning of screw lengths and trajectories

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to evaluate for spinal cord or nerve root involvement

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Posttraumatic instability

Infection/tumors involving the posterior elements

Postlaminectomy instability/kyphosis (post-tumoral decompression)

Congenital/syndromic cervical abnormalities

Cervical kyphosis (Larsen syndrome, diastrophic dysplasia, chondrodysplasia punctata [Conradi syndrome], camptomelic dysplasia, and neurofibromatosis)

Cervical abnormalities of segmentation/formation (VACTERL, Klippel-Feil syndrome)

NONOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

Stable cervical spine deformity with no neurologic involvement can be treated with observation and serial imaging.

Unstable cervical spine, neurologic involvement, or progressive deformity would be indications for surgical management.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Many techniques of posterior cervical fusion including wiring, plate and screw, and rod and screw constructs have been described.

Lateral mass screw fixation provides benefits compared to nonrigid fixation including fixation of patients with posterior laminar element deficiency, providing immediate stability, and allowing for greater deformity correction.

Preoperative Planning

Fine-cut CT evaluation to preoperatively plan screw lengths and trajectories, note any anomalous anatomy and assess location of the vertebral artery.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree