Fig. 7.1

Typical location of plantar fasciitis

7.3 Clinical Findings

Plantar fasciitis has a classic presentation of pain with ambulation after rest, also known as post-static dyskinesia. Athletic patients may feel more discomfort in the “warm-up” phase of their activity; symptoms may subside after a few minutes of initiating their sport. In the early stages in the injury, the pain will subside after a few minutes or even steps, but in the chronic stages, the pain may not subside with ambulation at all. There is often a point of maximal pain at the plantar medial aspect of the calcaneus.

Patients may or may not be able to relate a causative factor for the onset of the pain. Literature review fails to identify an exact cause or foot type for this injury, but theories for the etiology of this injury include pes cavus, pes planus, overpronation, underpronation, excess weight, improper shoe gear, training errors, ankle equinus, lack of proper fat padding, and occupations that require standing for long periods of time.

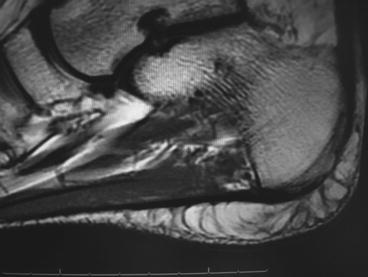

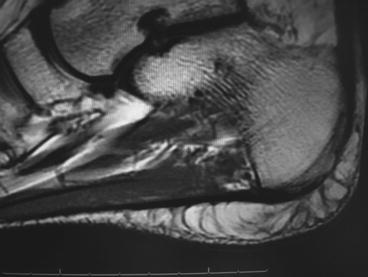

Plain radiographs may show the presence of a calcaneal heel spur. The spur has little effect on the cause or treatment of plantar fasciitis. Radiographs may be of clinical importance in ruling out fracture, erosive changes associated with a systemic arthritis or bone tumors. MRI and diagnostic ultrasound will show thickening of the fascia to at least twice the normal thickness9,10 (Fig. 7.2).

Fig. 7.2

MRI showing thickened plantar fascia

7.4 Plantar Fascia Rupture

Rupture of the fascia may follow chronic long-term plantar fasciitis, occur acutely, or as a sequella of treatment such as after injection.11–14 Most often the patient will relate feeling a pop or sudden sharp pain at the insertion of the medial or central band. Saxena and Fullem found an average return to activity of 9 weeks for athletes following this injury.11 Patients often have bruising in the arch associated with the rupture (Fig. 7.3). Correlation of patients symptoms with the bruising is more than enough evidence of rupture but MRI provides more conclusive evidence (Fig. 7.4).

Fig. 7.3

Bruising associated with plantar fascia rupture

Fig. 7.4

(a) MRI sagittal view showing plantar fascial rupture. (b) MRI transverse view showing medial plantar fascia and abductor rupture

The treatment of a rupture differs greatly from the treatment of plantar fasciitis. Initial treatment should be aimed at reducing pain and inflammation through the use of non-weight-bearing, a below-knee walking boot, ice, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and/or narcotics if needed. Within 1–3 weeks, the patient should be able to progress to full weight-bearing in a boot and in another 1–3 weeks progress out of the boot to full weight-bearing. An arch support or foot orthosis placed inside the boot may be helpful. Physical therapy can be started very early in the process and should focus initially on helping to relieve symptoms through the use of electrical stimulation (for swelling and pain control), pulsed ultrasound, and soft tissue mobilization. It should then progress to strengthening the foot and leg to transition out of the boot and back to full activity.11

7.5 Nonsurgical Treatment of Plantar Fasciitis

Since a majority of patients with plantar fasciitis get better with nonsurgical (conservative) treatment, it is worthwhile for presentation. There are no universal protocols to eliminate all the symptoms. Initial treatment, particularly in athletic patients, is to focus on stretching, reduce activity, and add arch support. Patient should perform a simple wall stretch concentrating on improving the flexibility of the gastrocnemius–soleus complex. The fascia does not have any elastic fibers and attempting to stretch the fascia by hanging off a step or putting your toes up against the wall may actually prolong the injury. However, DiGiovanni et al. presented an alternative method of non-weight-bearing specific stretching of the fascia which in their study worked better than the wall stretching.15

Ice can help control symptoms and is best performed by freezing water in a round smooth plastic bottle and rolling the foot over the bottle for at least 10 min, twice a day. Oral anti-inflammatories, both steroidal and nonsteroidal, can be utilized, though recent research has shown, as is the case with Achilles tendonosis, acute inflammatory pathological findings do not exist. If NSAIDs relieve symptoms, it is likely they are providing an analgesic effect. It may also be likely an arthridity is involved.

Avoidance of barefoot and adherence to wearing shoes with good arch support is also important in the initial treatment phase. Taping can be very effective at reducing symptoms and also may help aid in the diagnosis. Plantar fasciitis pain can be relieved the majority of the time through taping consisting of a low-dye with a Campbell’s rest strap over the top of the low-dye. Patient can be instructed to perform the taping themselves before activity. Alternative taping can be variations of the “plantar figure-of-eight” method (Fig. 7.5). Immobilization can be recommended for chronic cases, though ideally this should be reserved for calcaneal stress fractures and plantar fascia ruptures.

Fig. 7.5

Plantar “figure-of-8” taping. Additional reinforcement can be applied with traditional “low-Dye” taping

Corticosteroid injection can be very effective at reducing symptoms but is not without risks. Plantar fascia ruptures have been associated with injections, and multiple injections in the same area can lead to fat pad atrophy.12–14 The associated ruptures could possibly be dose and type-of-steroid related. Higher doses of insoluble steroids may have a more deleterious effect. Acevedo and Beskin reported that 10% of their patients were injected for plantar fasciitis with 40 mg/mL of triamcinalone acetate.12 One author (BF) prefers a mixture of 1.0 cc of 25% marcaine, 4 mg of Dexamethasone phosphate, and 5 mg of triamacinalone acetate with fewer than10 post-injection fascial ruptures in 18 years of practice.

Over-the-counter arch supports should also be considered for the initial treatment phase. If symptoms persist, a custom orthotic device can be considered. A softer device should be used for the cavus/underpronated foot type while a more controlling device should typically be prescribed for the pes planus/overpronated foot type. Biomechanical examination and the patient’s past experience should be combined with the physician’s expertise to devise the best orthotic device. Examination of the athletic patient’s shoe type is also paramount. Often sport shoes with arch cut-outs can instigate or aggravate plantar fascia conditions by allowing improper flexibility in the wrong region (Fig. 7.6).

Fig. 7.6

Improper shoe flexibility predisposing plantar fascia or midfoot injury

Extracorporeal shock wave therapy (ESWT) is generally offered as a last resort in the United States before considering surgical management. Shock wave therapy is purported to ultimately work by improving the vascularization to the injured area. The treatment induces micro-trauma to the area, and during the repair process, new blood vessels develop to deliver nutrients to the area and heal the tissue. There are virtually no long-lasting negative effect from the treatment: cost and availability being the main deterrent in the United States. There are both high-energy and low-energy machines. High-energy machines use a protocol of one treatment but requires anesthesia. Critics of this method cite that the painful area, when under anesthesia, may actually not be treated. The low-energy machines (Storz AG, Taegerwilen, Switerzerland) do not require local anesthesia, thereby allowing for “patient-focused or -directed” treatment (Fig. 7.7). Low-energy protocol requires three treatments usually spaced 1 week apart. Athletic patients being treated with low-energy machines are often able to continue their sport. Evidenced-based medical literature mainly finds long-term success rates of over 70%.16–20 Some studies show a high percentage of benefit from placebo (greater than 40%).17,21