Introduction

There can be little doubt that planning should be a central feature of the coaching process and of coaches’ practice. This is true both of the single session within the short-term introductory programme and of the multi-year major games preparation cycle. In fact, planning has come to have a taken-for-granted place in coach education, analyses of practice, and prescriptions for good practice. When coaches have been asked to identify the most significant elements in the coaching process, a number of studies have confirmed the central role of planning (Gould et al., 1990 and Lyle, 1992).

It is important to ask why a focus on planning is important. The context is the emerging and ongoing debate about the nature of the coaching process and the extent to which coaching behaviours and decisions are based firmly on planned interventions or more problematically subject to such a dynamic and ‘messy’ environment that there is a high level of contingency and immediate originality (Jones and Wallace, 2005 and Cushion et al., 2006). This debate focuses not only on questions about how planning might take place, but also on what ‘can be planned for’. Recently, Cushion (2007a) has argued that coaching expertise has ‘limited roots’ in planning or reason, and I have countered that there is a strong foundation of planned intervention (Lyle 2007), albeit subject to what I would argue is the everyday applied expertise of the coach in managing the vagaries of intervention. I have pointed out that there may be a difference between individual sports, particularly those that are not ‘circuit’ (an extended series of tournaments of events) or league sports, in which the planning intention may be more systematically applied, and team sports, in which the complexity of the process presents further challenges. Cushion’s rejoinder (2000b) was that there is a need for more evidence that has been derived ‘from’ practice in order to improve our understanding as a precursor to prescription. This implicitly draws a distinction between building a model ‘of’ practice, one that is based on evidence of coaches’ practice, and a model ‘for’ practice that is more derivative and prescriptive. This chapter is a result of the quest to base an understanding of planning behaviour in team sports on evidence from coaches’ ‘real time’ experiences. One of the key characteristics of this enquiry is that it was based on planning processes that had been identified in advance, applied over the course of the season, and subject to reflection.

At this stage it is necessary to clarify a number of assumptions. First, the focus within the chapter is on ‘planning the intervention’, that is, the training and competition programme directed by the coach towards identified targets and goals. Second, this is not a question of ‘systematic coaching’ versus ‘structured improvisation’ (Cushion et al 2003) as some of the literature has mistakenly labelled the debate. There may be some sports in which the planning intentions and intervention practice are unproblematically similar, and there are relatively few factors that interfere with a tightly planned and principled athlete workload. However, depending on the context, we might assume that coaching delivery requires an active process in which coaches make an almost continuous series of decisions about the most appropriate conduct and progression of the intervention in the context of a set of individual, group and organisational goals. This management of content and momentum is not the sole prerogative of the coach, but for the sake of simplicity, we can use this shorthand and assume that some of the decision making involves the players/athletes and other coaching personnel. Common sense tells us that often the conduct of the intervention will match the detailed intentions of the planning process, and at other times the coach will depart from the plan, or perhaps operate within more flexible guidelines. The vagaries of human effort, emotions, and motives, the response to training stimuli, the diverse interpretations of the technical model, and the complex interactions of team sport performance each and all combine to create a dynamic coaching environment. This may have contributed to a lack of coaching research focused on planning.

There is an absolute dearth of literature examining the planning process in coaching in any rigorous or conceptual way. To sports scientists applying, for example, physiological research and consequent principles to training schedules this may seem overstated. However, to understand this we have to look at how planning ‘knowledge’ has been developed and to appreciate the language or discourse that has developed around it. Planning to improve performance was subject to the application of ‘training theory’ (Schmolinsky, 1983 and Dick, 1997). It is not a coincidence that each of these authors was focused on athletics. The training principles were primarily derived from principles of physical conditioning and underpinned by exercise physiology. They applied most readily to sports in which the outcomes were determined by energy outputs (and technique). Intricate and sophisticated cyclical combinations of volume, intensity and duration of training were prescribed, and a great deal of attention was paid to peaking for maximum performance. Sports-specific literature identified different coaches’ approaches to the most appropriate balance and manipulation of performance factors (for example, in swimming, Councilman 1968). Perhaps the most significant influence was the work of Tudor Bompa (Bompa 1999). He provided a catalogue of ‘menus’ under the general rubric of ‘periodisation’. Bompa’s work also referred to team sport planning. General principles were provided that suggested a balance of technical, tactical and physical components in pre- and competition cycles. Although this ‘bio-scientific driver’ for coaching practice was based on sound principles, it might be argued that it was often divorced from application, and contributed to a formulaic approach to some aspects of intervention. In some sports it may also have created a ‘separateness’ between physical conditioning and coaching.

The term periodisation has come to be synonymous with planning, although it will be clear later in the chapter that there is a tendency for this to be conceptualised in its diagrammatic form, rather than as a planning process. Within periodisation the preparation and competition programmes and training contents are shaped (normally) by the competition schedule, and the plan operates on the premise that the optimum performance will be facilitated by a cyclical, progressive, incremental, and selective attention to interdependent components of performance. The extent to which this framework needs to be amended as objectives change or the environment changes, and the extent to which daily or weekly planning is derived directly from this plan are problematic issues for team sports. There are unresolved issues about the optimum length of the planning period and whether (some) team sports are susceptible to detailed content planning. This refers to the fact that sports with a high level of performer interaction (the ‘invasion sports’) and significant degrees of freedom in execution may find it difficult to identify and regulate ‘loading factors’ (volume and intensity of practice).

There are also obvious questions for the researcher about how planning can be ‘represented’, how coaching’s multiple objectives can be reconciled, whether or not ‘plans’ can be compared, and how the coaching context can be given a weighting. As a result, we have a planning ‘literature’ that is sports-specific, driven by physical conditioning, more obviously applied to individual sports, and based on prescription rather than research. There is remarkably little about planning in the refereed journals – perhaps a reflection of a lack of conceptual or theoretical depth. It tends to be dealt with in books and in coach education materials. This is in part a function of the methodological challenges in demonstrating comparative effectiveness and in experimenting with such a complex mix of planning variables, particularly over extended periods of time. There may also be an element of coaches not wishing to share more widely the detail of their plans. One of the most obvious factors is that the planning process and the success of the outcomes are likely to be influenced by the intensity of and commitment to the preparation process by players. Without prejudging our conclusions, it seems inevitable that the different coaching ‘domains’ (Lyle, 2002 and Trudel and Gilbert, 2006) will demand different approaches to planning. Whether or not the planning prerequisites (evidence rich, clear goals, technical model, sufficient duration) are in place may become clearer as the planning models emerge.

The aim of this chapter

This chapter process specifically for team examines the planning process for team sports coaches. In particular it identifies the lessons to be learned from the planning practice of experienced rugby union coaches. I suggest that there is relatively little merit in treating planning as a generic or abstract process, other than to identify planning principles in a context-less fashion. To progress the field, we need the detail-rich experiences of coaches who exercised a measure of accountability for the plans they were executing. It needs to be made clear that the chapter is not about the technical matters that form the foundation of the planning content. The emphasis is on the process that coaches engage with in their planning and the range of planning models that emerge from the coaches’ practice. The substance of the chapter is derived from an analysis of the planning intentions, implementation and subsequent reflections on a season’s planning by coaches who were taking part in the Rugby Football Union’s Level 4 coach education programme (this is the highest of four levels of coach education and is designed for experienced coaches). The author delivered a workshop for coaches on this course; part of the process was that coaches had to prepare plans for the coming season. These were submitted and feedback was given on some of the issues that might arise. The coaches implemented their plans, and prepared a summary document that reflected on the season’s planning and the lessons they had learned. The author received these reports and provided feedback (permission was received from the Coaching Development Manager at the Rugby Football Union to use these coach education submissions for analysis. I’m very grateful to the RFU and to the coaches concerned).

The purpose of the chapter is to contribute to the literature available on this element of coaches’ practice by describing models of coaches’ planning in a team sport, and discussing the issues that arise in their implementation. The first part of the chapter presents an overview of planning principles. This is intended to create a vocabulary and a context for the rugby union coaches’ practices. This part of the chapter is derived from the author’s experience as a coach and a coach educator, and the ‘working’ of this material over many years. This is followed by the analysis and interpretation of the rugby union coaches’ planning reflections.

The planning process in coaching

Planning for coaching implies a degree of pre-determination of preparation and an accounting for the consequences of actions over a given period of time. The underlying premise is that benefits can be achieved from the accumulation, integration, sequencing and aggregation of the various elements of preparation for performance; in addition, that this management of the intervention process is necessary for these benefits to be achieved effectively and efficiently. One way of conceptualising the coaching process is to recognise the intention to reduce chance and the unpredictability of performance, and that this requires the harmonisation of the contributory elements of the process. If we accept that there is an intentional aspect to achieving this (and undirected practice is unlikely to lead to optimum progress), planning becomes a prerequisite for coaching, although the practice of planning will be shown to vary enormously in its application.

Planning like coaching more broadly cannot be presumed to be unproblematic. The coaching process operates in an unstable environment, performance is made up of a challenging range of components, there are often multiple goals, and these are contested by others. Jones (2006) sums this up by suggesting that coaches and athletes often work with unattainable goals in a context in which they are not fully in control of all the factors involved. Interactive team sports are a particular subset of the coaching process and bring their own challenges for the planner.

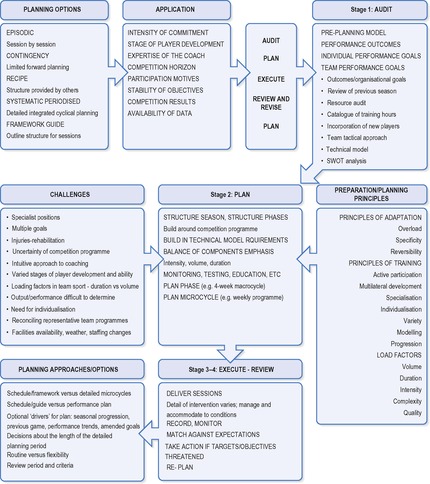

A schematic of the planning process is provided in order to establish the vocabulary and illustrate something of the issues involved in planning (Figure 6.1). As the evidence from rugby will further demonstrate there are a number of options in how planning is conceived of and used, and these are determined by a series of largely contextual matters. Planning can range from the episodic (session by session approach) to integrated cyclical planning using a training principles-informed periodisation. The session or phase of sessions may also be characterised by the level of contingency involved (ranging from the completely ‘seat of the pants’, to a guiding structure, and to detailed training workloads). An additional layer of analysis is provided by a continuum from ‘recipe planning’ to continual redevelopment and innovation. Recipe planning implies the use of existing or ‘borrowed’ session plans from published sources, sport-specific technical materials, fellow coaches, or the coach’s own repertoire. Coaches may elect to employ a combination of these variations as a matter of habit, education, situated learning, rational choice, pragmatism or ideology.

|

| Figure 6.1 • |

Nevertheless, it is possible to identify a range of contributory factors, most of which emanate from the scope and scale of the coaching process. An intensity of engagement (with a requirement for planning over the longer term, and preparation for specific games/competitions) can be gauged from a combination of the stage of player development, participation motives, and intensity of commitment. Data follow from continual monitoring and evaluation of performance, and the presence or absence of detailed performance data will ultimately limit the range of planning and planning implementation practices.

Planning procedures

The most basic and often-cited process in coaching is described as ‘plan–do–review’. This is a useful reminder that planning is important and that it is an iterative and cyclical process. A more elaborate description would be ‘audit, plan, execute, review and revise, execute’. This cyclical process implies that there is a strategic blueprint that is subject to revision, and that the implementation of the coaching process is being monitored and fed back into the planning process at regular intervals. In this case, the plan itself may be a guiding template or a more detailed predetermination of activity.

The audit stage involves identifying the extent of the intervention programme (this is termed the pre-planning model in which the number of hours are identified), the existing feedback on performance, individuals’ progress from the previous season, and the goals for the coming season. These goals or objectives provide a direction for the planning but have to be understood in the context of longer-term ambitions, changes of personnel, re-interpretation of the performance model, and the anticipated performance demands implied by the goals (how will we need to play to achieve our outcome goals and what does that mean for individual players). The audit stage is important, partly to understand subsequent changes to the conditions, and partly because detail (e.g. total coaching hours, individual goals) is often assumed, rather than specified. This stage also assumes an extensive (relative to context) knowledge and awareness of technical matters, of the likely opposition, and of the players. The audit should embrace the coaching and support staff, organisational resources, known competition markers, facilities, equipment, and other building blocks. Coaching effectiveness and expectation about outcomes need to be understood in relation to the planning audit. The interesting issue is the extent to which these ‘conditions’ can be influenced or altered by the coach. Coaches’ accountability and employment may be based on outcomes that are influenced by conditions about which the coach has limited control. The coach may control training content, game preparation and intensity of preparation, in addition to awareness of the environment. However, there will be less control over personnel, organisational goals, resources, and competitor progress.

The next part of the planning process is the design of the coaching intervention. This is often represented in diagrammatic form and this ‘plan’ has come to be symbolic of the planning function. It should be noted, however, that there are many important steps before this stage, and, assuming that planning is an active process, a continuous process of implementation, review, and re-planning. Our purpose at this point is merely to outline the planning process and not to construct a primer on design and content. The illustrative examples from the rugby coaches will identify some of their planning practice.

The season’s plan is usually built around the competition programme, although there may be some adjustments as a result of additional or delayed fixtures. This provides a simple differentiation into pre-season (or preparatory), competition season, and post-season (or ‘off’). However, there are many potential variations. The pre-season will typically be characterised by an emphasis on physical preparation with technical work remaining high in terms of volume and tactical preparation moving from general to specific and gradually assuming greater importance. This phase is also characterised by ‘pre-season games’. These are an opportunity for rehearsal, experimentation and a gradual development of readiness for competition. Coaches will often differ in their approach to this menu of games. The competition season may be quite extensive and there is merit in dividing it into sub-phases. This may be assisted by mid-season breaks, by cup competitions, by representative matches, or by a particular series of (perceived) difficult and less-difficult games. These sub-phases are important because they can provide a framework for physical preparation which itself needs to be periodised.

The subdivision of each of the phases creates a series of macrocycles, for example, the first half of a season, say 12–16 weeks, which is then divided into mesocycles of, perhaps, 4 weeks. These mesocycles are then divided into smaller planning units – usually one week microcycles. At various stages the plan will be populated by testing/monitoring dates, medical screening, review periods and so on. However, the implication from planning in this integrated and sophisticated way is that the physical, technical and tactical (and to some extent psychological) components will differ in their character and content in each phase. However, they are inter-dependent, both from one cycle to another, and on the other components. The training interventions will manipulate volume, duration, intensity and complexity, according to training prescriptions. The various energy systems are similarly balanced, and the coach’s technical model is rehearsed and developed. There is an assumption that longer- and shorter-term needs are being accommodated within the plan.

For some team coaches this attempt to create an integrated plan, with its high level of detail on workloads may seem like an unattainable or undesirable process. Nevertheless, it provides a set of expectations against which we can contrast the coaches’ practice. It should not be assumed, however, that the planning process as described here is unproblematic. The following list of confounding factors will not only apply to all coaches but also in concert create a dynamic environment, which makes it difficult both to prescribe training content and to evaluate its effectiveness:

• The need to deal with specialist position within teams and the consequent demands on performance components.

• The complex interaction of individual, team and organisational goals over the longer- and short-term.

• The inevitability that many goals will become unattainable as the season progresses.

• Player availability in terms of injury, rehabilitation, illness, re-location, transfers, retirement (and by implication the absorption of new players).

• Changes to the competition programme may be weather postponements, extended success in cup competitions, or simply fixture congestion. It may be possible to plan for some of these possibilities.

• Team sports will inevitably have a mixture of player abilities and stages of development. This will impact significantly on physical preparation and the technical model, and may be problematic for attempts to individualise the programmes.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree