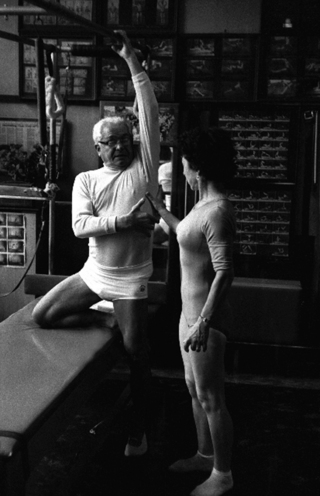

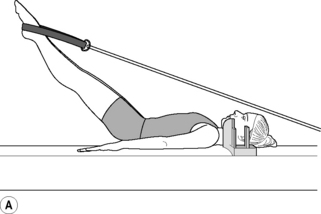

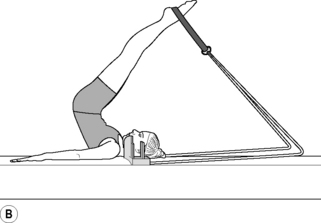

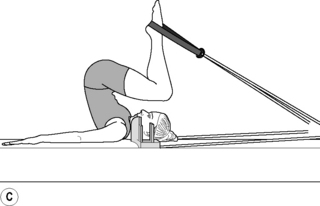

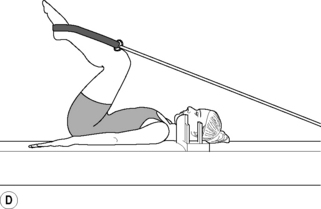

7.22 Pilates and fascia Pilates is regarded by its proponents as a comprehensive method of exercise and total body conditioning, created and pioneered by Joseph H. Pilates (1880–1967). The integrity of the method strongly rests on six basic principles: concentration, control, centering, precision, flowing movement, and breathing (Pilates 1945, 1998). Pilates’s methodology and approach to fitness and health took shape from 1914 to 1918 while he was detained on the Isle of Man as a prisoner of war. While living in the camp, he taught other residents the series of exercises that he had developed for personal use over the preceding decades, both in Germany and England (Redfield 2009). He created makeshift equipment from bed springs and frames to support and supplement his movement repertoire. Pilates immigrated to the United States in 1926 (Pilates 1927). The design of the Pilates exercise sequences was strongly based on Yoga and the principals of Zen (Pilates 1945, 1998). Zen, as an established sect of Buddhism, means meditation, ‘waking up’ to the moment. This mindfulness and awareness is integrated in the Pilates movement with the objective of uniting the body and mind. Pilates’s goal was a well-balanced body, with equal importance placed on both internal and external development. He established this balance by creating movement sequences that focus on rhythmic breath, stimulating both circulation and lung capacity. The movements that followed directly involved the spine. The function of integrated breathing aims to cause elastic movements of both the thoracic and abdominal cavities, and therefore, via the fascial connections, to affect the motility and circulation of the internal organs within the thorax, as well as in the abdomen and pelvic floor (Calais-Germaine 2005). The visceral organs contained in these cavities are divided by the respiratory diaphragm, which also unites them. The thorax is connected via the pleurae of the lungs and via the pericardium to the diaphragm of pulmonary fascia. The abdominal cavity is connected to the diaphragm by the peritoneum and connects the two cavities. Pilates’s movements, choreographed with the breath, are designed to stimulate movement originating from within, with the effect of breathing as described in Yoga principals (Pranayama) to control the mind (Iyengar 1966). Pilates’s early connections and collaborations involved the New York dance community, and its leading figures, including Ted Shawn, Ruth St. Denis and George Balanchine. His ‘contrology’ (explained below) teachings became heavily influenced by dance movement and the vocabulary of both classical and modern dance. This, coupled with his athletic background as a boxer and gymnast, is reflected in all Pilates exercises (Eismen & Friedman 2004). The Pilates Method focuses on postural symmetry (alignment), breath control, center/core strength, spine–pelvis, and shoulder stability, well-balanced muscle tone and joint mobility through its complete range of motion (Pilates 1945, 1998). Extensive research in fascia reveals dense and irregular connective tissue continuity through the entire body that envelops and connects every muscle myofibril and internal organ (Schleip 2003; Huijing & Langevin 2009). It functions as a flexible ‘soft tissue skeleton,’ offering support, form and tensile tone through the entire body. The second nature of this mechanical fascial matrix involves neuro-communication. The ability to adapt, change and influence other systems in the body relates to the presence in fascia of a variety of mechanoreceptors and the presence of smooth muscle cells (myofibroblasts). The integrated system communicates tension and compression, thereby affecting cellular function (Ingber 1998). In that Pilates movement emphasizes control through oppositional length tension, it challenges and stimulates the tensegrity geometry (Fuller 1961) of the entire body, promoting biomechanical health and strength (Myers 2009). Fascia, through the presence of myofibroblasts, forms an indirect link to the autonomic nervous system, further affecting the quality and tone of the muscular system, which may be influenced by breathing disorders (pH changes), emotional stress, or diet (Myers 2009, Oschman 2003). In contemporary life, movement and range of motion that support a healthy body may be compromised by stressful environments. For example, a ‘desk-bound’ lifestyle and lack of activity may lead to a fascial-bound, stagnating structure (Beach 2010). Rather than isolating muscle groups, the focus in Pilates rests on whole-body integration as a possible means to restoring fascial length, healthy texture, and optimal tissue hydration and resilience. Myers (2009) (see also Chapter 7.21) has described how yoga movements can be seen to specifically affect and apply to fascial tracts (‘meridians’). Similar parallels can be made with Pilates; for example, in exercises such as the ‘Short Spine Massage’ or ‘Short Spine Stretch,’ a traditional Pilates exercise performed through optimal length tension, omnidirectional and full-range articulated control, affecting the different fascial ‘lines.’ Fig. 7.22.2 • A Short Spine Massage, preparation and posturing – this addresses and loads the deep fascial front line (DFL). B Short Spine Massage, phase 2 – this is an extension of the full superficial backline (SBL). C Short Spine Massage, phase 3 – this phase eccentrically loads the lateral line (LL) and both functional lines (BFL and FFL). D Short Spine Massage, phase 4 – this is the resting and control phase. ©1998 Marie-Jose Blom, www.pilatesinspiration.com Pilates achieves this effect by positioning and placement of the body. Unlike yoga, Pilates dynamically takes the body into specific repetitious movement patterns, ideally performed through full range, uniting breath control and precision. The movements are performed in a manner that reinforces full oppositional length tension, emphasizing eccentric control, which affects tensile stimulation through the entire network. Within the Pilates paradigm, this effect is thought to transfer into other areas of life with measurable results of coordination, strength, mobility, posture, grace, and self-confidence (Pilates 1945, 1998; Eismen & Friedman 2004). Pilates emphasized the importance of ‘being present’ and being in the moment during the exercises, while paying attention to every detail of each movement (Pilates 1945, 1998). Attention to detail is considered to promote an openness to explore and experience, that is, to stimulate the learning process (Doidge 2007). Through focused practice, this process is viewed as contributing to the change and ‘remodeling’ of the myofascial structures, influenced by the neural impulses delivered to it. As such, using the fascial systems is posited to be a learning and information medium. In this perspective, the fascial and myofascial system, densely populated with feed-back and feed-forward mechanoreceptors, expands the opportunities for learning, change and remodeling. Schleip (2003) indicated that the fascial field not only reacts to verbal instruction, but also responds effectively to tactile corrective or directive instruction. Reinforcement by imagery, or ‘idio-kinesis,’ has also been observed to produce similar physical changes in the motor system (Franklin 1996; Doidge 2007). Fig. 7.22.3 • Optimizing proprioception through positional correction with touch or props. ©2007 Robert Reiff, www.magiclight.com This contemporary motor-learning model is intended to provide the environmental conditions for training of the feed-forward, or core, system and to enhance timing and motor skill coordination, which in turn stimulates neuro-plasticity (Doidge 2007). Over time, this process is thought to lead to new motor patterns that override established compensatory movements that may cause biomechanical strain. Concentration and embodiment of the movement in Pilates is considered to enhance coordination of the neuromuscular system with the myofascial system (Oschman 2003; Myers 2009). The emphasis on concentration on the entire body, through each movement, as opposed to compartmentalization, parallels the contemporary science-based anatomy models of a ‘myofascial’ or ‘neural-myofascial, skeletal’ continuum, organized and stimulated by directed movement patterns (van der Wal 2009; Myers 2009). Movement patterns that are sequenced to follow the organization of the densely innervated fascial system are considered both to render deep structural support and to provide position-sense of the body and its movement in space. Pilates proponents posit that this result forms an integrated memory bank and communication system for retraining healthy movement. That is, optimal movement leads to a healthy structure, i.e., ‘form follows function’ (Wolff 1986). For example, in the Pilates footwork on the universal reformer, the correct placement of the feet will transfer the movement along the entire kinetic chain via fascial pathways. When optimal foot positioning is not achieved in these movements, proprioceptive communication and retraining may be compromised (Myers 2009). Positional correction with touch or props (towel) has been observed to optimize proprioception and improve concentration through embodiment.

The art of ‘working in’

Introduction

The blend of Eastern and Western philosophies

Fusion and integration of various disciplines

Fascia, bound by lifestyle, can Pilates make it move?

Pilates principles and fascia

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Musculoskeletal Key

Fastest Musculoskeletal Insight Engine