, Antonio Cesarani2 and Guido Brugnoni3

(1)

“Don Carlo Gnocchi” Foundation, Milano, Italy

(2)

UOC Audiologia Dip. Scienze Cliniche e Comunità, Università degli Studi di Milano, Milano, Italy

(3)

Istituto Auxologico Italiano, Milano, Italy

Abstract

The syndrome of phobic postural vertigo (PPV) was described by Brandt, and it is characterized by subjective dizziness and a disturbance of balance while standing and walking, despite normal values in clinical balance tests. The key lesion is a shift in the coordination of open- and closed-loop mechanisms of postural control: patients with PPV use sensory feedback inadequately during undisturbed stance, and this impairs postural performance, while equilibrium control is normal when a difficult balance task, such as tandem stance on foam rubber with eyes closed, is required just like to that of healthy persons in the same stance conditions. In PPV patients, subjective imbalance is caused by inappropriate balance strategies with higher levels of antigravity muscle activity and co-contraction during the conscious concentration on control of postural stability. The consequent key impairment is postural fear and the key disability is a decreased motor and social autonomy due to a phobic behaviour. Treatment is aimed to obtain the unconsciousness of postural control, reducing energy expending. Thus, rehab has to be pointed to restore correct integration between special and general proprioception and the correct internal representation of posture in order to recover appropriate balance strategies

The syndrome of phobic postural vertigo (PPV) was described by Brandt [1], and it is characterized by subjective dizziness and a disturbance of balance while standing and walking, despite normal values in clinical balance tests.

PPV is sometimes considered as one of the primary and secondary somatoform dizziness syndromes [2–4] or a visual vertigo [5] or a chronic subjective dizziness [6]. Anyway, it is one of the most frequent causes of chronic dizziness. PPV sometimes represents an impaired compensation of a vestibular neuritis with a consequent high impact on quality of life [7].

Instrumented analysis of postural sway in PPV reveals subtle abnormalities such as increased muscular energy expenditure and high-frequency body sway during quiet standing [8, 9].

The key lesion is a shift in the coordination of open- and closed-loop mechanisms of postural control: patients with PPV use sensory feedback inadequately during undisturbed stance, and this impairs postural performance, while equilibrium control is normal when a difficult balance task, such as tandem stance on foam rubber with eyes closed, is required just like to that of healthy persons in the same stance conditions [10].

In other words, in PPV patients, subjective imbalance is caused by inappropriate balance strategies with higher levels of antigravity muscle activity and co-contraction during the conscious concentration on control of postural stability.

In fact, in normal subjects, maintenance of balance is achieved unconsciously and conscious control is required only in unusual and therefore unadapted balance tasks, e.g. on slippery ground or when walking on a beam. The performance of the postural control system in PPV is changed in two ways:

The steady-state behaviour of the open-loop control mechanisms is significantly altered.

The effective range of the open-loop regime is shortened and the feedback threshold of the closed-loop regime is reduced.

Thereby the open- and closed-loop control system as a whole is not optimally tuned. The control systems are working but in an inadequate way, so that they are not as smoothly and efficiently functioning as in healthy subject.

The consequent key impairment is postural fear and the key disability is a decreased motor and social autonomy due to a phobic behaviour.

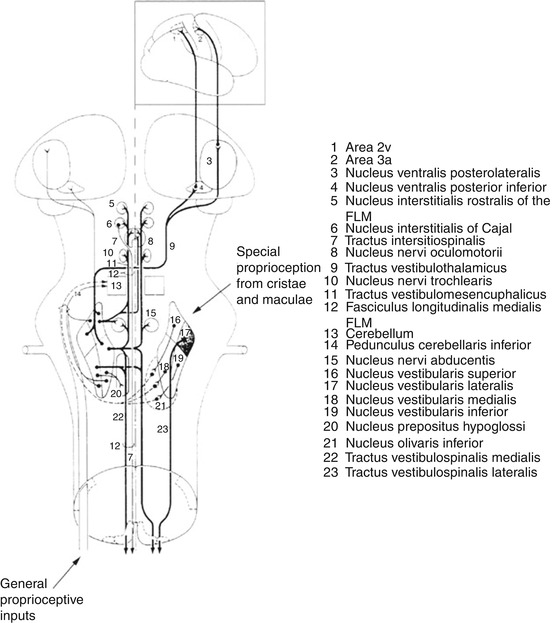

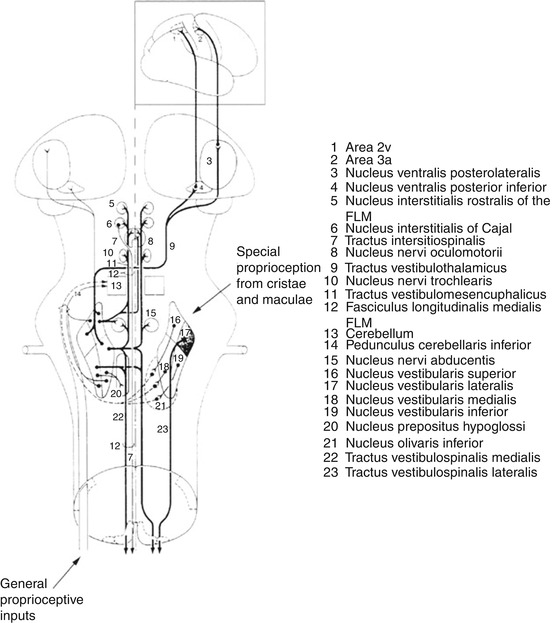

Patients with PPV use sensory feedback inadequately during undisturbed stance, and this impairs postural performance and the subjective imbalance further increases conscious control of posture. This condition is sustained by a mismatch between general proprioception (from muscle, ligaments and joints) and the special proprioception (from maculae and cristae) during postural control. The integration and elaboration of general and special proprioception by cerebellum has been proposed by Drukker [11, 12]. He described the connections of the vestibular system to the spino-cerebello-vestibulospinal circuitry (Fig.13.1): proprioceptive inputs from muscles, ligaments and joints are integrated and elaborated in the cerebellum together with information from maculae and cristae and then from cerebellum efferent pathways return to spinal motoneurons through another elaboration in the vestibular nuclei (with special regard to the lateral Deiter’s nucleus).

Fig. 13.1

The connections of the vestibular system: efferent connections of the vestibular nuclei and the spino-cerebello-vestibulospinal circuitry: the so-called spino-cerebello-vestibulospinal circuitry is shown. General proprioception information (from muscles, ligaments and joints) is integrated and elaborated in the cerebellum together with special proprioception information from maculae and cristae. From the cerebellum, efferent pathways return to spinal motoneurons through another elaboration in the vestibular nuclei (with special regard to the lateral Deiter’s nucleus) (Originally published in Cesarani et al. [14] published by Springer ©1996)

13.1 Treatment

Treatment is aimed to obtain the unconsciousness of postural control reducing energy expending. Thus, rehab has to be pointed to restore correct integration between special and general proprioception and the correct internal representation of posture in order to recover appropriate balance strategies.

13.1.1 First Week

1.

2.

The patient lifts her/his pelvis taking simultaneously extending the arms extended over her/his head. She/he then repositions the arms along the body, lowering the pelvis.

3.

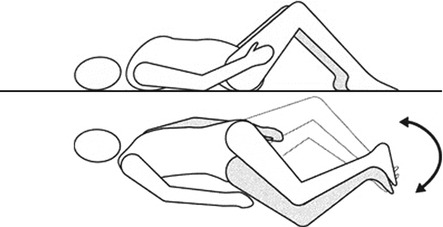

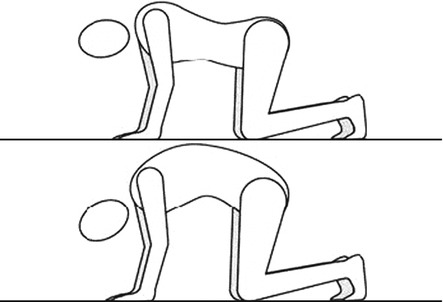

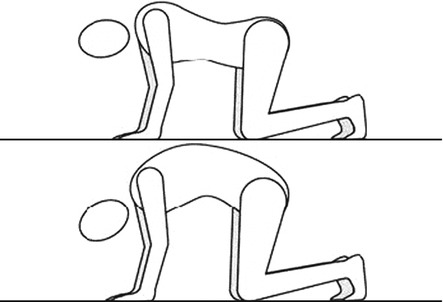

In the quadrupedal position, the patient inhales and arches her/his back (hyperkyphosis), holding the head between the arms. She/he then exhales, flexing the head and rotating the pelvis in hyperlordosis (Fig. 13.3).

Fig. 13.3

Movements of the pelvis in the quadrupedal position (Originally published in Cesarani and Alpini [15] published by Springer © 1999)

4.

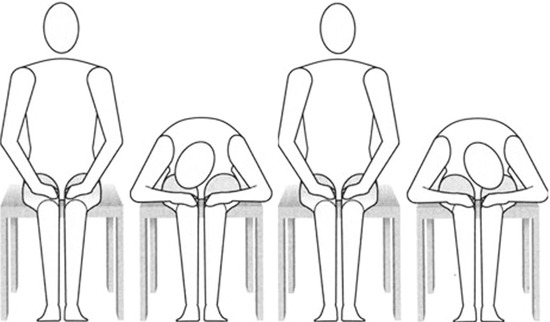

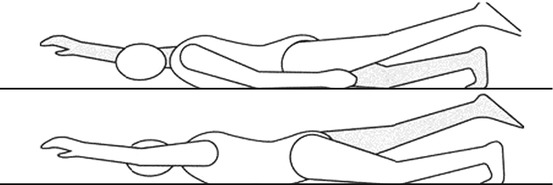

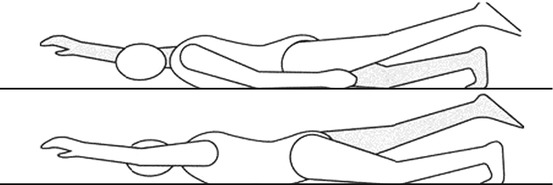

In the prone position, the patient lifts her/his left arm and the right leg while holding her/his forehead over the bed. She/he repeats with the right arm and the left leg (Fig. 13.4).

Fig. 13.4

In the prone position, simultaneous extension of one arm and the opposite leg (Originally published in Cesarani and Alpini [15] published by Springer © 1999)

5.

She/He repeats the procedure as above but also simultaneously lifting the head.

6.

In the sitting position, the patient first inhales. Then, exhaling, she/he bends forward holding the head on the right knee. She/he waits 10 s and then, inhaling, she/he returns to the sitting position. Then, exhaling, she/he bends forward holding the head on the left knee. She/he waits 10 s and then, inhaling, she/he returns in the sitting position (Fig. 13.5).