Phakomatoses and Other Neurocutaneous Syndromes

Sharon E. Plon

NEUROFIBROMATOSIS

Neurofibromatosis (NF) is the term used for a set of distinct disorders that share some clinical characteristics, with NF types 1 and 2 being described most clearly. NF type 1 (NF-1) previously called Von Recklinghausen disease, accounts for at least 85% of all patients with NF and is one of the most common dominant genetic disorders.

Neurofibromatosis Type 1 (Von Recklinghausen Disease)

NF-1 occurs with a frequency of approximately 1 in 2,500 to 4,000 persons. It is inherited as an autosomal dominant trait, with an affected parent having a 50% risk of transmitting the disease to each child. However, approximately one-half of the index cases represent new mutations, so that a negative family history is a common finding in the pediatric setting, and children with features of NF-1 should be evaluated regardless of family history. The disorder is essentially the same whether it is inherited from an affected parent or results from a new mutation. The likelihood that a person with an NF-1 mutation will have clinical features of the disease (termed the penetrance) is close to 100%. However, the severity of NF-1 is highly variable in its expression from one family to another, from one person to another within a given family, and from one body part to another within a given person. Additional information concerning the genetics and molecular biology of NF-1 is presented in Box 416.1.

Clinical Manifestations and Complications

Because of the difficulty of performing molecular analysis, most patients are diagnosed on clinical grounds. A checklist of the

features that are characteristic of all types of NF, with an emphasis on NF-1, is provided in Box 416.2. Café au lait spots (CALS) (hyperpigmented macules) are the hallmark of NF-1. Segmental NF refers to the rare patients who have clinical features of NF in only one segment of the body, and CALS are limited to that area. CALS are seen variably in patients with NF-2 but typically are much fewer in number compared with patients with NF-1. Small numbers of CALS also are seen in other cancer-predisposing syndromes and thus are not specific to the neurofibromatoses.

features that are characteristic of all types of NF, with an emphasis on NF-1, is provided in Box 416.2. Café au lait spots (CALS) (hyperpigmented macules) are the hallmark of NF-1. Segmental NF refers to the rare patients who have clinical features of NF in only one segment of the body, and CALS are limited to that area. CALS are seen variably in patients with NF-2 but typically are much fewer in number compared with patients with NF-1. Small numbers of CALS also are seen in other cancer-predisposing syndromes and thus are not specific to the neurofibromatoses.

BOX 416.1 Genetics and Molecular Biology of Neurofibromatosis Type 1

The gene mutated in NF-1 (NF1) resides on the proximal long arm of chromosome 17, specifically in band 17q11.2. However, it is a very large gene, with no major hotspots of mutations, which has limited clinical testing for NF1 mutation. One exception is the finding that approximately 5% of patients have deletion of the entire gene, which is associated with significant developmental delay, early development of neurofibromas, and dysmorphic features.

DNA genetic linkage analysis of large numbers of families with NF-1, along with molecular analysis of translocations involving chromosome band 17q11.2, has resulted in the rapid identification and cloning of the NF1 gene. The NF1 gene product, neurofibromin, is expressed in virtually all tissues studied, from both normal individuals and those with NF-1. Neurofibromin functions to regulate the activity of the ras-mediated signaling pathways, which implies, in turn, that loss of neurofibromin at key times in a cell’s life may lead to abnormal growth promotion. Loss of the remaining normal copy of the NF1 gene (termed loss of heterozygosity) has been documented in MPNST, myeloid malignancies associated with NF-1, and some neurofibromas. Thus, NF1 appears to function as a tumor-suppressor gene. However, mouse models containing mutations in the paralogous gene have demonstrated that the development of tumors results both from the neoplastic cell losing the second copy of the NF1 gene and supporting cells (including mast cells) containing the inherited NF1 mutation. Thus, new treatment research is focusing on inhibiting the function of these supporting cells to decrease tumor burden.

In patients with NF-1, CALS are larger than 15 mm in diameter and have sharply defined edges and a uniform intensity of coloration (Fig. 416.1). CALS often develop during the child’s first year of life and increase in number during the first few years. The pattern of CALS then stabilizes. CALS are different from freckling, which in NF-1 is most likely to occur in regions of skin apposition, particularly the axilla. Multiple (six or greater) CALS may be the only feature of NF-1 in a 1-year-old child and are sufficient to merit a full diagnostic evaluation for NF-1.

Neurofibromas are of four types: cutaneous, subcutaneous, nodular plexiform, and diffuse plexiform. Cutaneous neurofibromas are the most common variety, eventually occurring in virtually all patients with NF-1. Often, they do not appear until just before the patient enters puberty or coincident with it. They are present in highest density over the trunk (Fig. 416.2). Subcutaneous neurofibromas usually become apparent toward the end of the first decade of life or in early adulthood, and they may be painful or tender. Nodular plexiform neurofibromas are complex clusters of subcutaneous-like neurofibromas along proximal nerve roots and major nerves. With continued growth along the spinal column, they lead to spinal erosion and, eventually, spinal cord compression. Diffuse plexiform neurofibromas, with or without overlying hyperpigmentation, are congenital lesions that tend to enlarge steadily with age (Fig. 416.3). Both diffuse and nodular plexiform lesions can result in significant morbidity and deformity.

BOX 416.2 Anatomic-Structural and Functional Features in Neurofibromatosis Type 1

Anatomic-Structural Features

Skin pigmentation

Café au lait spots; freckling: axillary, elsewhere; hyperpigmentation over a plexiform neurofibroma; other hyperpigmentation; hypopigmentation

Discrete neurofibromas

Cutaneous: general, areola, nipple; subcutaneous;oral-pharynx-larynx; deep

Plexiform neurofibromas

Craniofacial: orbital, other; chest wall; paraspinal: cervical, thoracic, lumbosacral; abdominal, retroperitoneal; limb; visceral

Central nervous system (CNS)

Orbit: glioma, other; intracranial: chiasm, other; astrocytoma, schwannoma, meningioma, other; spinal

Other tumors

Schwannoma (non-CNS); malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor; pheochromocytoma; carcinoid; other benign; malignancy

Ocular

Lisch nodules; hypertrophied corneal nerves; choroidal hamartomas; congenital glaucoma; eyelid ptosis; cataracts

Skeletal

Short stature; macrocephaly; craniofacial dysplasia; vertebral dysplasia; kyphoscoliosis/scoliosis; lumbar scalloping; pseudoarthrosis: tibial, other; genu valgum/varum; pectus excavatum; other skeletal

Miscellaneous

Colon ganglioneuromatosis; xanthogranulomas (skin); vascular: angiomas, renal, cerebral, other; pulmonary fibrosis; cerebrospinal fluid: ventricle dilation, hydrocephalus, other abnormality; excess dental caries; electroencephalographic abnormality; other anatomic features

Functionl Features

Cosmetic disfigurement; hypertrophic impairment; weakness/paralysis; incoordination; pain; seizures; other neurologic features; strabismus; visual impairment; hearing impairment; speech impediment; developmental delay; learning disability; school performance problems; mental retardation; psychosocial burden; psychiatric symptoms; headache; puberty disturbance; pruritus; constipation; gastrointestinal bleeding; hypertension; surgery; other functional features

Lisch nodules (lesions of the iris) are relatively specific for NF-1. They develop over the course of time and are present in

fewer than 10% of patients with NF-1 who are younger than 6 years old. Ninety to 100% of NF-1 patients who are older than 10 years old have Lisch nodules, and thus they are a very helpful diagnostic finding. If large in size or number, Lisch nodules may be easy to see with an ordinary ophthalmoscope, but ruling out their presence requires careful slit-lamp examination by an ophthalmologist who is familiar with these lesions. The examination of parents for the presence of Lisch nodules (coupled with a skin examination) can be very useful in determining whether an affected child carries a new mutation or inherited it from an affected parent. It is important to reassure parents that the development of Lisch nodules does not impact vision.

fewer than 10% of patients with NF-1 who are younger than 6 years old. Ninety to 100% of NF-1 patients who are older than 10 years old have Lisch nodules, and thus they are a very helpful diagnostic finding. If large in size or number, Lisch nodules may be easy to see with an ordinary ophthalmoscope, but ruling out their presence requires careful slit-lamp examination by an ophthalmologist who is familiar with these lesions. The examination of parents for the presence of Lisch nodules (coupled with a skin examination) can be very useful in determining whether an affected child carries a new mutation or inherited it from an affected parent. It is important to reassure parents that the development of Lisch nodules does not impact vision.

FIGURE 416.2. Cutaneous neurofibromas often are not apparent until puberty and are present in highest density over the trunk. |

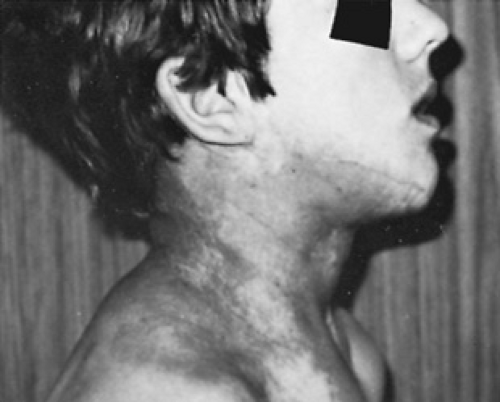

FIGURE 416.3. Plexiform neurofibromas, with or without overlying hyperpigmentation, are congenital lesions that have variable growth patterns during childhood and adolescence. |

Optic pathway tumors (OPT) are characteristic of NF-1, occurring in 15% of patients with this disorder. In approximately 5% of children with NF, these lesions result in morbidity, including blindness, thus necessitating a careful ophthalmic examinations of all young children with NF-1. However, given the variable natural history of these lesions and the controversy concerning appropriate treatment, no consensus with regard to recommendations for routine neuroimaging to detect these lesions presymptomatically has been established. In addition to having optic gliomas, children with NF-1 are at increased risk for developing other central nervous system (CNS) neoplasms. Neuroimaging of children with NF-1 utilizing T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed the frequent occurrence of areas that were unusually bright. These lesions have been referred to by many names, including unidentified bright objects, NF-1 bright spots, and, more recently, vacuolation changes. These lesions wax and wane and often disappear later in childhood. Whether the number of lesions correlates with any cognitive dysfunction is unclear. Although suggestive of NF-1, their presence is not a diagnostic criterion.

Learning disabilities, distinct from mental retardation, are present in 40% to 60% of children with NF-1. These disabilities may be foreshadowed by a delay in attaining developmental milestones, but in any event, they usually are apparent by the time the child begins the first grade of school. Mental retardation occurs in approximately 8% of patients with NF-1, but its presence should not be presumed to be the result of NF-1 until an investigation for other causes has been completed and found to be negative or unrevealing. Mental retardation and dysmorphic features are found with children who have a large deletion encompassing the whole NF-1 gene. Speech impediments may involve articulation or language elements and usually are obvious by the time the child is 3 years of age.

Pseudoarthrosis, or bowing of the tibia, may occur as an independent lesion, but it often is one of the characteristic congenital lesions of NF-1. The congenital nature of the pseudoarthrosis may be masked by a delay in diagnosis until weight bearing or walking is attempted. Any child with tibial pseudoarthrosis should be evaluated thoroughly for other clinical features of NF-1. Sphenoid wing dysplasia is another congenital skeletal feature of NF-1. Similar to pseudoarthrosis, it is a congenital primary bony dysplasia, although sometimes an associated orbital or periorbital diffuse plexiform neurofibroma may occur.

The scoliosis that is typical of NF-1 usually involves the cervical and upper thoracic spine and has an anterior angulation (kyphosis). It frequently becomes apparent in children between 6 and 10 years of age, although the presence of a hair whorl overlying an area of vertebral dysplasia (Riccardi sign) at an earlier age may presage future problems.

Renovascular hypertension is one of the clinical problems of NF-1 that can be anticipated and treated effectively. All individuals who have NF-1 are at risk for developing the disorder and must receive regular blood pressure monitoring, regardless of their age, although adolescents and pregnant women are most likely to be affected. Pheochromocytoma is another source of systemic hypertension, both intermittent and sustained. NF-1 patients with hypertension should be evaluated for these two causes of hypertension.

Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor (MPNST), previously referred to as neurofibrosarcoma, has an overall lifetime incidence of 3% to 5% among patients with NF-1. Although the magnitude of this risk may be small, the relative risk is at least two orders of magnitude above that of the general population, and NF-1 patients diagnosed with MPNST have a very poor prognosis. These malignancies usually are found in an area of a preexisting plexiform neurofibroma. Thus, a MPNST must be ruled out in a child with a history suggestive of such a lesion (i.e., pain, acceleration in growth of a plexiform lesion, a rapidly enlarging tumor, or an otherwise unexplained neurologic deficit).

Several other common medical conditions show an increased frequency in NF-1, one of which is puberty disturbance. More important, premature or delayed puberty may indicate the presence of a chiasmal or hypothalamic glioma. Short stature is seen in at least 16% of patients with NF-1, and growth curves for children with NF-1 are available. Macrocephaly also is present in 16% or more of affected patients. This finding not always is apparent in infancy and is not correlated with any known functional compromise.

Natural History

The timing of onset of the features of NF-1 is well established (Box 416.3).

Congenital Features

Congenital glaucoma may occur in approximately 1% of infants with NF-1, and screening for glaucoma should be included in the ophthalmic evaluation of infants with NF-1. Tibial pseudoarthrosis may be obvious by congenital bowing of the distal leg, or it may not become apparent until weight bearing or ambulation is attempted. Diffuse plexiform neurofibromas almost always are present at birth, but they may be subtle (i.e., apparent only from associated overlying hyperpigmentation or large CALS) or internal (e.g., apparent only on radiographic studies). Sphenoid wing dysplasia sometimes is associated with an orbital or periorbital diffuse plexiform neurofibroma. Similarly, vertebral dysplasia occasionally is associated with a diffuse plexiform neurofibroma, but it is unlikely to be a source of concern until later in childhood.

Infantile Features

Optic-pathway gliomas often are detected first on MRI neuroimaging during the child’s second year of life. They usually are not apparent clinically until visual compromise can be appreciated by a parent or clinician and, in some cases, not until the tumor mass causes proptosis. Thus, significant visual compromise may occur in children with OPT if the diagnosis of NF-1 is not made and ophthalmic evaluation not initiated. In most cases, children who have no evidence of optic pathway involvement on neuroimaging by the time they are age 3 years are very unlikely to develop symptomatic OPT later in life. Also, as noted previously, CALS become apparent when the child is between 6 and 18 months of age.

BOX 416.3 Features of Neurofibromatosis Type 1 as a Function of Age

Congenital

Glaucoma; plexiform neurofibromas; pseudoarthrosis; sphenoid wing dysplasia; vertebral dysplasia

Infancy to 6 Years

Optic-pathway glioma; café au lait spots; learning disability; mental retardation; speech impediment; seizures

6 to10 Years

School performance problems (including learning disability); scoliosis, with or without kyphosis; iris Lisch nodules

Preadolescence and Adolescence

Cutaneous and subcutaneous neurofibromas; accelerated growth of plexiform neurofibromas; psychosocial burden; hypertension resulting from renovascular involvement; malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor

Adulthood

Variable increase in number and size of cutaneous and subcutaneous neurofibromas; hypertension resulting from renovascular involvement; malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor; pheochromocytoma

Often, the parents of a young child with NF-1 are concerned that he or she will have diffuse plexiform neurofibromas and, as a result, be seriously disfigured. In general, these lesions develop early in childhood and if not evident (on careful examination) by middle childhood are unlikely to develop. Moreover, even in children with a diffuse plexiform neurofibroma, the prediction of growth is difficult and extreme disfigurement is unusual.

Later Childhood Features

School performance problems resulting from learning disabilities usually become important in patients with NF-1 in the middle to later years of childhood (8 to 14 years). Lisch nodules in the iris cause no clinical problems, but their presence in patients with NF-1 after 6 years of age is so consistent that after that age a child without Lisch nodules or CALS is very unlikely to have NF-1. Scoliosis or kyphoscoliosis usually becomes apparent when the child is between the ages of 5 and 10 years, a fact that supports particularly close follow-up during this period with early recognition and prompt treatment by an orthopedist.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree