Periprosthetic Joint Infection: Surgical Technique One-Stage Exchange

Daniel O. Kendoff

Michael B. Cross

Matthew P. Abdel

Thorsten Gehrke

Case Presentation

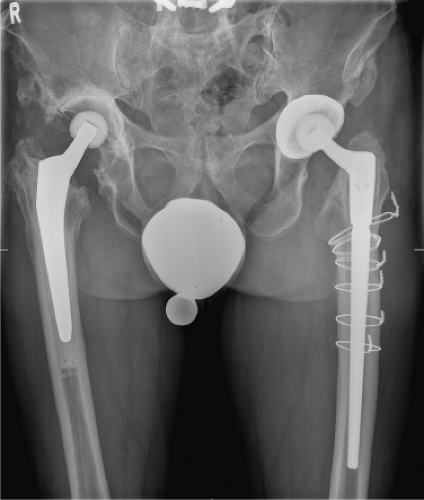

A 68-year-old male underwent a right uncemented primary total hip arthroplasty (THA) at an outside institution in 2009. Subsequently, he developed a late chronic infection with Staphylococcus capitis and underwent a two-stage exchange in 2010. The first stage included a resection arthroplasty for 12 weeks. Because of persistent wound issues, he was in the hospital for 10 weeks. However, reimplantation was then undertaken. Unfortunately, in 2012, he presented with a recurrent infection and underwent a repeat two-stage exchange for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). At the time of reimplantation, he had cemented acetabular and femoral components placed (Fig. 95.1). The patient then presented to our clinic in 2013 with persistent pain, an elevated C-reactive protein (CRP), an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), and a total white blood cell (WBC) count of >8,000 in the synovial fluid. Aspirate cultures revealed Staphylococcus epidermidis and Propionibacterium acnes after 12 days of incubation.

Introduction

Periprosthetic joint infections (PJIs) remain a serious problem, despite modern diagnostic modalities, operative interventions, and medical management (including novel antibiotics and antifungals). The overall therapeutic goal in either one or more staged revisions of PJI is complete eradication of the infection and further maintenance of joint function.

It has been widely accepted that late chronic infections should be treated with a two-stage exchange technique. A less commonly utilized technique is a one-stage exchange, an approach that has been utilized in our clinic since the 1970s with good results (1,2,3,4,5). A careful review of the literature reveals similar results between one- and two-stage exchanges for the treatment of PJI (6,7,8,9).

However, one-stage exchange offers certain advantages. These include the need for only one operative procedure, reduced hospitalization time, reduced overall costs, and improved patient satisfaction in some series (10). Although advantages exist, there are obligatory details that need to be meticulously followed to obtain a successful result with a one-stage exchange.

Indications

At our institution, 85% of all infected cases are treated with a one-stage exchange. A prerequisite is an identifiable

bacterium based upon preoperative aspiration that is susceptible to antibiotics that can be placed into the bone cement. In addition, host factors must be taken into consideration, such as obesity, diabetes mellitus, and other immunocompromised conditions. Further, it is essential to have an experienced surgical team and an infectious disease specialist who is engaged with the team to guide antibiotic treatment. Finally, a radical debridement is absolutely essential to a successful one-stage exchange.

bacterium based upon preoperative aspiration that is susceptible to antibiotics that can be placed into the bone cement. In addition, host factors must be taken into consideration, such as obesity, diabetes mellitus, and other immunocompromised conditions. Further, it is essential to have an experienced surgical team and an infectious disease specialist who is engaged with the team to guide antibiotic treatment. Finally, a radical debridement is absolutely essential to a successful one-stage exchange.

Contraindications

There are several contraindications to a one-stage exchange. These include, but are not limited to:

Failure of two or more previous one-stage exchanges

Infection involving the neurovascular bundle

Unidentified bacteria preoperatively

Lack of appropriate antibiotics that can be mixed into the cement

Multidrug-resistant organism

Preoperative Planning

Joint Aspiration

With any suspected PJI, a joint aspiration is mandatory. This is a mandatory part of our practice when evaluating any painful total joint arthroplasty. In regard to one-stage exchanges, this allows preoperative identification of the bacteria so that local and systemic antibiotics can be tailored (11,12).

Imaging

Serial radiographs (including anteroposterior [AP] pelvis, AP of the affected hip, and cross-table lateral) are essential to determine if osseous signs of infection are present. We rarely obtain nuclear imaging studies.

Discussion of Specific Risks

Prior to a one-stage exchange, the risk, benefits, and alternatives are discussed with the patient. This includes a risk of recurrent or new infection (10% to 15%), possible hematoma or wound complications, possible sciatic nerve injury, and risk of intraoperative or postoperative fractures and dislocation.

Anesthesia

The anesthesia team plays a critical role in the success of a one-stage exchange. This includes administration of perioperative tranexamic acid and managing the patient’s blood loss with fluids and/or bank blood.

Surgical Preparation

It is imperative that the surgeon be aware of exactly what prostheses are implanted in the patient prior to any surgical intervention. In addition, the amount of acetabular and femoral bone loss should be estimated preoperatively so that appropriate implants can be prepared. Bone loss is usually clinically significantly greater than that radiographically evident. Severe cases may even require total femoral replacement. Moreover, the surgeon should be prepared for intraoperative complications, such as periprosthetic fractures. Finally, high-dose antibiotic cement must be available and utilized in every case. We prefer high-viscosity cement typically, 80 to 120 g (which is equivalent to 2 to 3 bags), which most frequently contains 0.5 g gentamicin and 2 g vancomycin per 40-g package of cement and is available to us as a commercially prepared preparation.

Operative Technique

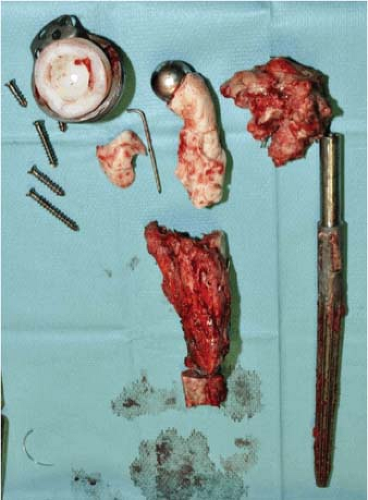

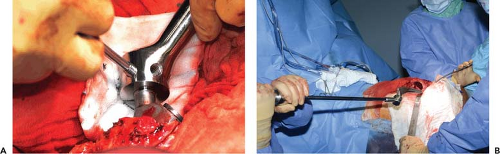

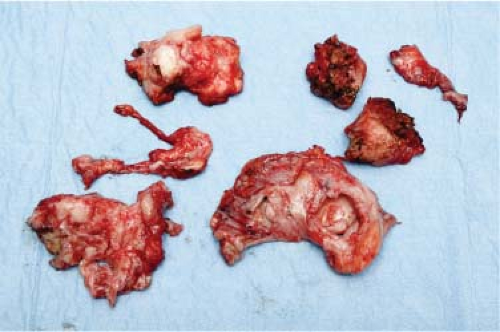

The foundation of a one-stage exchange not only depends on meticulous removal of all foreign materials, but also on a radical debridement and placement of high-dose antibiotics into the cement. This includes a radical debridement of the anterior and posterior capsule of the hip joint, which must be done routinely in any one-stage approach to the hip joint and usually exceeds the resection done during a two-stage approach, including all affected osseous structures (Figs. 95.2 and 95.3).

Skin Incision and Initial Debridement

Old scars in the line of the skin incision should be excised. If multiple incisions are present, the incision from the most recent procedure should be utilized. Sinus tracts, and their entire path, must be excised with the skin incision. In our opinion, a sinus tract does not represent a contraindication for a one-stage exchange. If musculocutaneous flaps are anticipated, a plastic surgeon should be available. Next, all nonviable tissue and necrotic bone must be radically excised. Five intraoperative cultures should be taken for combined microbiologic and histologic evaluations (13,14); we prefer to hold perioperative antibiotics until these cultures have

been obtained. This commonly includes a broad-spectrum cephalosporin with additional antibiotics tailored to the culture results (11).

been obtained. This commonly includes a broad-spectrum cephalosporin with additional antibiotics tailored to the culture results (11).

Figure 95.2. Radical debridement includes debridement of both the acetabular and femoral soft tissues and bony structures. |

Implant Removal and Completion of Debridement

In cases of well-fixed uncemented components, cortical windows are required to gain access to the interface. High-speed burrs and curved saw blades can also aid with removal. However, occasionally significant destruction and related bone loss can occur. As such, an extended trochanteric osteotomy (ETO) should be utilized. Our preferred method is to follow the below routine: