CHAPTER 5 Peripheral Tears of the TFCC: Arthroscopic Diagnosis and Management

Anatomy and Biomechanics

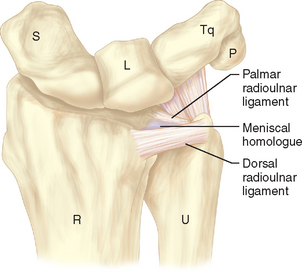

The anatomy of the triangular fibrocartilage complex (TFCC) is primarily composed of the articular disc (or triangular fibrocartilage), a meniscus homologue, dorsal and volar radioulnar ligaments, the extensor carpi ulnaris (ECU) tendon subsheath, and the ulnocarpal ligaments (ulnolunate, ulnotriquetral, and ulnocapitate)—as depicted in Figures 5.1 and 5.2. The triangular fibrocartilage is a meniscus-like structure composed predominantly of type I collagen. Surrounding the periphery of the triangular fibrocartilage is the meniscal homologue, a fibrocartilaginous rim of dense irregular connective tissue that confluences with the dorsal and volar radioulnar ligaments.1

The ligaments and the triangular fibrocartilage form a three-walled structure that supports the distal radioulnar joint and ulnar portion of the carpus. The TFC, with its bordering volar and dorsal radioulnar ligaments, acts as the base of this structure. These ligaments originate as a unit from the fovea of the ulnar head and the very base of the ulnar styloid (Figure 5.3) and diverge distally into dorsal and volar stabilizers for the distal radius as it rotates around the distal ulna to achieve forearm rotation.2 The ulnotriquetral, ulnolunate, and ulnocapitate ligaments form the volar wall of this box, and the dorsal radial triquetral ligament (along with the dorsal fibers of the ECU subsheath) forms the dorsal wall.

The dorsal ECU subsheath has Sharpey fiber connections to the ulnar head at the fovea.2 The ulnar fibers of the ECU subsheath make up the ulnar-sided wall. The ulnotriquetral and ulnolunate ligaments along the volar wall of the TFCC have been shown to extend distally from the volar margin of the triangular fibrocartilage and the volar radioulnar ligament, rather than from the ulna itself.2,3 This confluence of many ligaments on the ulnar aspect of the wrist stabilizes the ulnar carpus to the triangular fibrocartilage as the radius rotates around the ulna.

The blood supply and innervation of the triangular fibrocartilage enters from the periphery.4,5 Thiru et al. evaluated the vascular perforators to the TFCC in a cadaveric study.6 The ulnar artery provides the blood supply to the ulnar portion of the TFCC through dorsal and palmar radiocarpal branches. This ulnar periphery of TFCC has the richest blood supply and the best potential for healing after repair. The dorsal and palmar branches of the anterior interosseous artery supply the more radial periphery and the attachment to the distal radius. The central portion of the TFCC is essentially avascular and is not amenable for repair. Similarly, the radial/central portion has been shown to have essentially no innervation.7 The majority of nerve supply to the TFCC is also peripheral, with contributions from the posterior interosseous nerve, the ulnar nerve, and the dorsal sensory branch of the ulnar nerve (DSBUN).

The volar and dorsal radioulnar ligaments are the primary stabilizers of the distal radioulnar joint (DRUJ) during rotation and translation at the DRUJ. As the forearm supinates from a position of full pronation, the volar radioulnar ligament is under stress and lengthens in a viscoelastic manner to accommodate.8,9 Pronation, from a position of full supination, causes the dorsal radioulnar ligament to be stressed and subsequently lengthen.8,9 A majority of the load from the carpus are directed to the radius (80%), whereas the remainder (20%) is directed to the ulna through the TFCC.10

There continues to be dispute among authors as to the advantages of either arthroscopic or open surgery for tears of the TFCC. Significant DRUJ instability has been demonstrated with complete release of the foveal attachments of the TFCC.11,12 In one study, the DRUJ instability was corrected with an open suture repair of the volar and dorsal radioulnar ligaments through bone tunnels to the fovea or an open version of the arthroscopic repair of the ulnar TFCC to the ECU subsheath.12 Biomechanical testing demonstrated significant improvements in the stability of the DRUJ for both groups. However, it was noted that the weakest aspect of each repair was not the type of repair but the bioabsorbable polydioxanone suture used.

Patient Presentation

Upon physical examination, acute TFCC injuries present with ulnar-sided wrist swelling. Point tenderness occurs when palpating the ulnar side of the wrist in the ballotable region between the ulnar styloid and the triquetrum. Forearm rotation with the wrist maintained in ulnar deviation may also elicit pain or a wrist click. The TFCC compression test is positive if axial loading of the ulnar side of the hand with ulnar deviation of the wrist results in significant pain. Similarly, de Araujo et al.13 described an ulnar impaction test that elicits pain by wrist hyperextension and ulnar deviation with axial compression. Although radiographs may not directly diagnose soft-tissue pathology in cases of suspected TFCC tears without carpal or distal radioulnar joint instability, indirect information can be obtained from the ulnar variance, the distal radioulnar joint congruency, and the presence or absence of a prior ulnar styloid or distal radius fracture.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with intra-articular gadolinium has become the imaging modality of choice for the diagnosis of soft-tissue injuries, and TFCC injuries are no exception (Figures 5.4 and 5.5). Although an MRI arthrogram may be both sensitive and specific in diagnosing a tear,14 at this point it has not been shown to be accurate in assessing tear size. In one study, Fulcher and Poehling felt that MRI understaged some TFCC pathology and overstaged others.15 Pederzini et al. performed arthrography, MRI, and arthroscopy on 11 patients with TFCC injuries.16 Although these authors found 100% specificities with sensitivities of 80 and 82% for arthrography and MRI (respectively), arthroscopic visualization of a TFCC tear continues to be the gold standard for definitive diagnosis.

Classification of TFCC Injuries

Anatomic, clinical, and biomechanical investigations have led to a classification of the triangular fibrocartilage complex injuries. Originally proposed by Palmer,17 this classification helps differentiate between traumatic and degenerative lesions. Repairable peripheral tears are generally classified as either type 1B or type 1C tears. Type 1B lesions are peripheral tears that occur as the ulnar side of the TFCC complex is avulsed from its capsule ulnar ligamentous attachments. These injuries are amenable to arthroscopic repair of the TFCC if there is no associated ulnar styloid fracture and no associated DRUJ instability. The type 1C injury involves rupture along the volar attachment of the TFCC or tears of the ulnocarpal ligaments. Type 1C tears may be amenable to repair if the ligamentous injury is vertically oriented. Arthroscopic repair of transverse or horizontally oriented tears of the ulnocarpal ligaments has not yet been described to our knowledge.

TFCC tears can be subdivided further by their time course from injury to treatment (Table 5.1).18 Tears are classified as acute when treated within three months from the time of injury. Arthroscopic repairs of acute tears can result in the recovery of up to 85% of the contralateral grip strength and range of motion.18 Acute injuries have a better prognosis than subacute injuries and chronic injuries.19 Subacute tears are treated from three months to one year after injury. Although subacute tears are still amenable to direct repair, in general they tend to regain less strength and range of motion than patients with repair of acute injuries.19 Chronic tears (more than one year) are repairable, but the results are inconsistent—presumably due to contraction of TFCC ligaments and degeneration of the torn fibrocartilage margins. Chronic injuries frequently require ulnar shortening osteotomy with or without TFCC debridement to decrease the load distributed to the ulna via the TFCC.

Table 5.1 Classification of TFCC Injuries

| Class 1: Traumatic |

| Class 2: Degenerative |

Indications

Whereas repair of the peripheral triangular fibrocartilage attempts to recreate the original anatomy with direct suture of a rent in the fibrocartilage or its peripheral attachment, arthroscopic repairs involve imbrication of the peripheral-most aspect of the TFCC to the neighboring wrist capsule. This imbrication restores the tautness and trampoline effect of the TFCC and thus improves the stability of the TFCC as well as the patient’s symptoms, but does not precisely replicate the pre-injury anatomy. If DRUJ instability exists, only an open and direct reattachment of the foveal origin of the volar and dorsal radioulnar ligaments can reliably and completely restore stability.20 However, patients frequently present with acute or subacute peripheral TFCC tears in the setting of a stable DRUJ. These patients are amenable to arthroscopic repair.

The specific indications for arthroscopic repair of periphery tears of the TFCC continue to evolve. If clinical assessment and diagnostic studies suggest a TFCC tear, a wrist arthroscopy is warranted for adolescent or adult patients assuming a few key prerequisites (presented in Table 5.2). The type of peripheral tear also plays a role in the indications for repair. Horizontal, oblique, and vertical tears of the periphery of the TFCC can be addressed. However, distal transverse tears involving the volar ulnocarpal ligaments (within the type 1C category) are not amenable to arthroscopic repair at this point. More proximal split tears can be repaired and these ligaments can be imbricated to augment lunotriquetral instability, as has been demonstrated by Moskal et al.21

Table 5.2 Prerequisites for Arthroscopic Repair of Peripheral TFCC Tears

< div class='tao-gold-member'> Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|