Diagnosis

Nerve injuries are easily missed in the turmoil of major injuries, or if the patient is drunk or upset. Testing should be done by comparing sides, not by asking the patient to close their eyes and then asking if they can feel you touching them. The second method is notoriously unreliable, while the first reliably warns you when a full formal neurological examination may be needed.

As a general rule penetrating wounds in the hand have always damaged a nerve until otherwise proven. Similarly, in the neck and spine it is best to assume the worst (there is an unstable fracture with potential for further nerve damage) until this possibility has been actively excluded (see Chapter 42). Some nerves, like the lateral popliteal (foot drop) and the radial nerve (wrist drop), are especially susceptible to injury because of their position close to bone with no soft tissue protection.

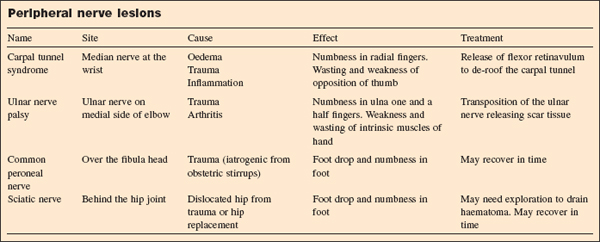

Peripheral nerve injuries

Chronic injuries

- The canal is narrowed by new tissue deposition such as osteophytes.

- There is local swelling and inflammation of tissues such as synovium in rheumatoid arthritis.

- There is generalised oedema such as occurs at menopause.

- A tumour in the nerve causes thickening of the nerve.

- There is excessive external pressure from the patient’s occupation such as using a pneumatic drill.

The common sites for the compression are the median nerve in the carpal tunnel at the wrist, the ulnar nerve on the medial side of the of the elbow joint, as well as spinal nerves as they pass through the intervertebral foramina. There are many others including Bell’s palsy and acoustic neuroma causing deafness.

Minor injuries

Minor compression of a peripheral nerve can lead to loss of function of that nerve for some days or even weeks. The nerve fibres are intact and physiological function returns in time without any need for tissue healing.

Severe injuries

- Incomplete severing of the nerve. In more severe injuries some of the fibres (axons) in the nerve may be severed but the overall structure of the nerve may remain intact. In these cases the axon proximal and distal to the cut dies (Wallerian degeneration), leaving the tunnel of Schwann cells (if it was a myelinated fibre) through which the fibre originally passed. This tunnel acts as a guide for a new nerve fibre to grow back at around 1 mm/day. The progress of the regrowth can sometimes be traced by tapping your finger over the path of the healing nerve. When you tap over the tip of the new growing fibre, the patient will experience electric shocks running down the arm.

- Complete severing of the nerve. An injury that completely separates the ends of the nerve cannot heal unless those nerve ends are brought back into close contact, preferably with the nerve fibre ends correctly aligned with each other. Otherwise there is a danger that the regenerating axon tip will set off down the wrong track thus compromising the function of the nerve. The repair of the nerve is best performed under an operating microscope to obtain accurate opposition; if there is a segment of nerve missing, then a nerve graft may be created from a length of another less important nerve to act as a guide to the regenerating nerve fibres.

Nerve recovery

- Nerve recovery tends not to be so good in the elderly, where the nerve fibres are very long, and where the nerve has a mixture of sensory and motor fibres.

- While waiting for nerves to regrow there is important work to be done by physiotherapists in preventing muscles from wasting, and joints from stiffening up.

- If there is also sensory loss then these areas may need to be protected from unnoticed damage, especially burns, which may lead to ulceration.

- Recovery of sensation can be tested using hair bristles of differing stiffness (noting the softest that the patient can feel), and by testing two point discrimination (the smallest distance between two pricks that can be distinguished as separate points).

Injuries to the central nervous system

The peripheral nervous system extends out from the spinal ganglia (dorsal for sensory, ventral for motor). The rest of the nervous system (pre-ganglionic) consists of the brain and the spinal cord. Injury to these nerves leads initially to a state of spinal shock (concussion) when the nerves fail to work at all. The spinal shock wears off over a period of hours or days and it is only then that the true extent of the damage to the nervous system will become apparent.

In spinal cord injuries, the finding that there is sparing of the central sacral roots is the first indication that there may be some recovery of function and that the transection of the cord is not complete. The central nervous system has very little capacity for tissue healing but has an extraordinary ability to reorganise so that damaged tissue is by-passed. This process takes time and this plasticity decreases with age.

As the spinal shock wears off, patients may get a false hope of recovery from the fact that their muscles are starting to contract. However, this may be spasticity setting in, a result of complete and irreversible nerve damage.

Brachial plexus injuries

If the arm is dragged down by a high energy impact (such as a fall from a high speed motorcycle), there may a tearing injury to the nerves coming from the neck through the brachial plexus into the arm. The injury can be a mixture of:

- Pre-ganglionic damage where the nerve roots actually pull out the ganglia.

- Post-ganglionic damage where the brachial plexus is torn apart.