Pericapsular Osteotomies of Pemberton and Dega

Tim Schrader

W. Timothy Ward

DEFINITION

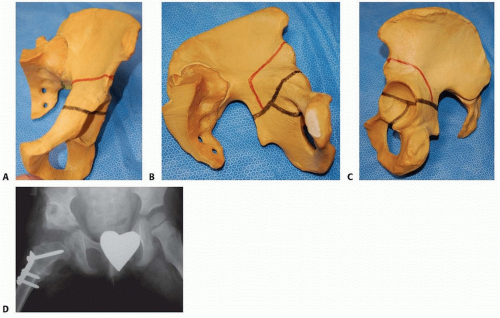

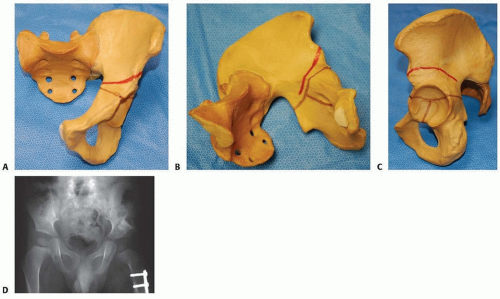

The Pemberton7 (FIG 1) and Dega1, 2 (FIG 2) osteotomies are performed for acetabular dysplasia that is either part of a developmental disorder or an acquired disorder due to muscle imbalance in neuromuscular conditions.

These are not reorienting procedures such as an innominate osteotomy but rather reshaping procedures that alter the geometry of the acetabulum and its volume.6, 11

They are used to increase anterior and lateral acetabular coverage.

ANATOMY

The acetabulum develops at the confluence of the growth centers of the ilium, ischium, and pubis.

Normal growth of the acetabulum requires not only that all of these growth centers remain open and function normally but also that the femoral head remains concentrically reduced and stable within the acetabulum.

If the growth centers are damaged, either from pathologic conditions or iatrogenically, or if the femoral head is not stable within the acetabulum, normal growth is unlikely to occur and hip dysplasia develops.

PATHOGENESIS

Because of an abnormality in the growth centers of the acetabulum, abnormal periosteal growth, or abnormal positioning of the femoral head, the acetabulum does not develop properly.

Even with a concentric reduction of the femoral head, the prior period of abnormal growth may prevent the acetabulum from achieving a normal configuration at maturity. The older the child is at the time of reduction, the more likely an osteotomy will be necessary to normalize acetabular appearance.

NATURAL HISTORY

Many patients with acetabular dysplasia develop subluxation or dislocation of the femoral head. This can lead to early arthritis as an adult.

The degree of subluxation does not necessarily correlate with the time to onset of symptoms or the degree of arthritic changes.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

Developmental hip dysplasia is a spectrum of pathology that can be diagnosed by physical examination in newborns and young infants if instability of the hip exists but may require ultrasonography or radiographs for diagnosis in cases of dysplasia without clinical instability.

Risk factors include breech position, female, firstborn, and oligohydramnios. Developmental hip dysplasia is associated with other “packaging disorders.”

Patients with a history of hip dysplasia are typically followed with radiographs until adulthood to ensure normal acetabular development.

Asymptomatic older children without a prior history of developmental hip dysplasia may be diagnosed on incidental radiographs taken for other reasons in cases of mild dysplasia or by history or clinical examination in those children who become symptomatic.

Symptomatic patients will present in childhood with one or more features including hip pain, limp, limb length discrepancy, or asymmetric hip abduction, particularly those with underlying neuromuscular conditions.

Routine screening for hip dysplasia using radiographs is widely performed in neuromuscular conditions.

Examinations and tests to perform include the following:

Ortolani test: Positive if a clunk is felt as a dislocated hip reduces.

Barlow test: Positive if a clunk is felt as a reduced hip dislocates.

Hip abduction: In a normal hip, abduction should be more than 60 degrees and symmetric. This may be the only abnormal sign in infants. A difference of 10 degrees or more is significant.

Galeazzi sign: A difference in thigh length is a positive result. A positive Galeazzi sign can indicate a dislocated hip, a short femur, or a congenital hip deformity.

Abnormal skin folds can occur in normal children but may alert the pediatrician to an underlying hip problem. This finding is neither highly sensitive nor specific.

Limp with ambulation, Trendelenburg sign, or limp associated with limb length discrepancy may be the only abnormal sign in older children.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Dynamic hip ultrasound can be used to detect hip dysplasia in very young infants (younger than 6 months of age).

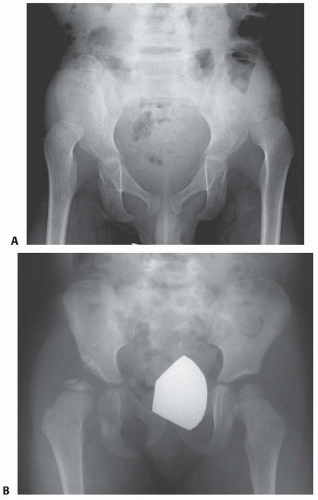

Plain radiographs, including an anteroposterior (AP) view of the pelvis, frog lateral, and false-profile views, typically can be used to make the diagnosis in older children.

Radiographic parameters, including the acetabular index, lateral center-edge angle, anterior center-edge angle, the position of the sourcil, and the line of Shenton, should be evaluated (FIG 3).

Dislocation is defined by lack of contact between the acetabulum and femoral head.

Subluxation is defined by a break in the line of Shenton.

Dysplasia is defined by a decrease in the lateral center-edge angle or an increased acetabular index on the AP pelvic radiograph or a decrease in the anterior center-edge angle on the false-profile view.

An AP pelvic radiograph taken with the legs abducted and internally rotated may show reduction of the femoral head implying that combined pelvic and femoral osteotomy would be expected to increase acetabular coverage.

A computed tomography (CT) scan, particularly with three-dimensional (3-D) reconstruction can provide a more detailed evaluation of anterior and lateral coverage.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Slipped capital femoral epiphysis

Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease

Congenital coxa vara

Proximal femoral focal deficiency

NONOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

Infants are typically treated with full-time braces, such as the Pavlik harness.

Young children can be treated with closed reduction and cast immobilization.

The initial treatment for primary acetabular dysplasia without hip instability or residual acetabular dysplasia following treatment for instability is observation.

As long as the acetabular index continues to improve and the hip remains concentrically reduced, observation can be continued.

If hip subluxation develops or the acetabular index fails to improve over a 12-month period, operative treatment is indicated.

Neuromuscular patients with a migration index less than 25% can be observed as long as their abduction remains greater than 45 degrees. Patients with migration indexes over 50% generally will benefit from surgical treatment of their dysplasia, which can include a femoral or pelvic osteotomy.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

The Pemberton and Dega osteotomies are incomplete transiliac osteotomies used to treat acetabular dysplasia with anterior and lateral deficiencies.

They are used when more than 10 degrees of acetabular index correction is needed.

They are also used to increase femoral head coverage during open reduction in a patient with severe acetabular dysplasia.

Preoperative Planning

Hip and knee contractures should be carefully evaluated preoperatively so they can be addressed during the surgical procedure.

With neuromuscular patients, the femoral head may be deformed. An open capsulotomy to look at the articular cartilage may prove to be beneficial.

If there is significant articular cartilage damage, particularly laterally from the hip capsule, a resection arthroplasty may be indicated as opposed to a reduction.

The primary area of acetabular deficiency needs to be determined to plan the osteotomy.

The triradiate cartilage should be opened because the osteotomy hinges on this cartilage. Generally, this osteotomy can be performed up to about age 10 to 12 years. After this age, hinging is less likely to occur at the triradiate cartilage and moves significantly to the symphysis pubis, resulting in less reshaping and more reorienting of the acetabulum.

Hip mobility must be good, especially abduction and internal rotation.

A concentric reduction of the femoral head in the acetabulum before the osteotomy is an absolute prerequisite. This can be assessed preoperatively with an abduction internal rotation hip radiograph or can be assessed intraoperatively after an open reduction or varus proximal femoral osteotomy.

Positioning

Patients are positioned supine on a radiolucent table with a bump under the lumbosacral spine to provide about 30 degrees of elevation of the ipsilateral hip (FIG 4).

A fluoroscopic evaluation should be done at this time to ensure adequate radiographic visualization.

The entire limb is prepared from the lower rib cage to midline.

TECHNIQUES

▪ Incision and Superficial Exposure for Both Osteotomies

Two different skin incisions have been described. The choice is determined by the need for concomitant femoral osteotomy but is fundamentally surgeon preference.

An anterolateral curvilinear incision starts 1 cm inferior and posterior to the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS) extending distally over the greater trochanter down the proximal femur. This incision is only used when anterior open reduction and femoral osteotomy is included. It is expansile and provides excellent visualization for all aspects of an open reduction combined with pelvic and femoral osteotomy (TECH FIG 1A).

Alternatively, a “bikini” oblique incision can be used, particularly if Dega or Pemberton osteotomy is done in isolation. This incision is more cosmetically appealing than the anterolateral curvilinear incision if the pelvic osteotomy is done in isolation. A separate additional lateral incision is used if femoral osteotomy is planned (TECH FIG 1B,C).

TECH FIG 1 • Skin incisions. A. An anterolateral curvilinear incision starts 1 cm inferior and posterior to the ASIS extending distally over the greater trochanter down the proximal femur. B,C. The more limited bikini incision provides plenty of exposure for the pelvic osteotomy, leaves an unassuming scar, and can be combined with a lateral incision for concurrent femoral osteotomies.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access