CHAPTER 39 Percutaneous tube management

1. Identify two primary reasons for using percutaneous tubes.

2. Distinguish among the placement approaches for gastrostomy and jejunostomy, including indications and overview of technique.

3. Explain why tube stabilization is a priority in the management of the patient with a percutaneous tube.

4. Describe at least two options for stabilizing gastrostomy or jejunostomy tubes.

5. For each complication listed, identify a prevention and management approach: peritubular leakage, tube migration, candidiasis, and tube occlusion.

6. Identify percutaneous tubes that can be irrigated and those that cannot be irrigated.

7. Describe routine site care for the patient with a percutaneous tube.

Although described in the thirteenth century, planned surgical gastrostomy as a procedure was first proposed in 1837 and performed 12 years later in 1849, with the first reported survival of the procedure performed by S. Jones in 1876 (Wu and Soper, 2004). Today the use of tubes is commonplace within the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, as well as other organs and spaces, on a temporary or a long-term basis. Percutaneous tubes are placed for a variety of purposes, including feeding, decompression, and drainage. The tubes are inserted into the desired body part by an interventional radiologist using computed tomographic or fluoroscopic guidance.

Gastrostomy and jejunostomy devices

A gastrostomy is an opening into the stomach, and a jejunostomy is an opening into the jejunum. Such procedures may be used to provide decompression or enteral support for a patient unable to ingest adequate nutrients orally (DeChicco and Matarese, 2003). Enteral nutrition offers many potential advantages over parenteral nutrition, including lower rates of infectious and metabolic complications, decreased hospital length of stay, and reduced cost. Many of the benefits of enteral feeding are in part due to preservation of gut integrity (histologic structure and physical viability) better than parenteral feeding (Fish and Seidner, 2003; Harbison, 2007). Enteral support is generally appropriate through a nasogastric or nasoenteric feeding tube for short-term access (i.e., less than 3 to 4 weeks) in the patient who is at low risk for aspiration (Bloch and Mueller, 2004; DeChicco and Matarese, 2003; Wu and Soper, 2004). When the risk of aspiration exists, postpyloric placement of a tube is preferred. The patient’s history and results of physical examination, barium studies, fluoroscopy, and manometry are useful when evaluating the patient’s risk for aspiration. Consultation with the neurologist and speech pathologist also is beneficial. Box 39-1 lists the risk factors for aspiration.

Placement approaches

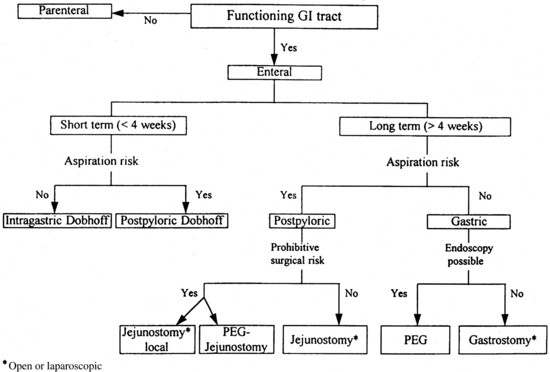

Today, a gastrostomy or jejunostomy is created by one of three approaches: surgical, endoscopic, or interventional radiologic. Open laparotomy is rarely performed due to the success of the much less invasive endoscopic and laparoscopic techniques (Duh and McQuaid, 2000). Figure 39-1 presents an algorithm for determining the most appropriate means of enteral access.

FIGURE 39-1 Enteral access algorithm for selecting the most appropriate technique for an individual patient.

(From Gorman RC, Morris JB: Minimally invasive access to the gastrointestinal tract. In Rombeau JL, Rolandelli RH: Clinical nutrition: enteral and tube feeding, ed 3, Philadelphia, 1997, WB Saunders.)

Surgical approaches

Open surgical procedure.

The most common open surgical procedures for gastrostomy tube placement are the Stamm, the Witzel, and the Janeway. The Stamm and the Witzel are the simplest procedures and are considered temporary; the Janeway is more of a long-term or permanent procedure (Bloch and Mueller, 2004; Gincherman and Torosian, 1996).

Stamm gastrostomy.

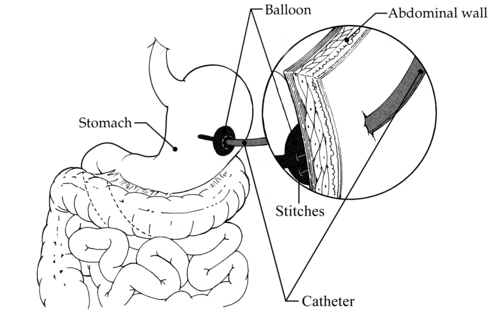

Stamm gastrostomy is the standard open gastrostomy, the gold standard for transabdominal gastric access (Harbison, 2007). Creation of a Stamm gastrostomy begins by making a small incision in the left upper quadrant of the abdomen. Another small incision is made over and through the body of the stomach, through which a catheter (Foley, mushroom, Malecot, or gastrostomy replacement tube) is inserted (Figure 39-2). Several pursestring sutures are used to invaginate the stomach around the tube. The stomach is then fixed to the abdominal wall at the catheter site, and traditionally a nonabsorbable suture is used to secure the catheter to the skin. Although the Stamm gastrostomy is the simplest surgical technique to perform and remove, it is frequently difficult to manage and is plagued with complications such as peritubular leakage, wound infection, peritonitis, and tube dislodgment (Beyers, 2003).

Witzel gastrostomy.

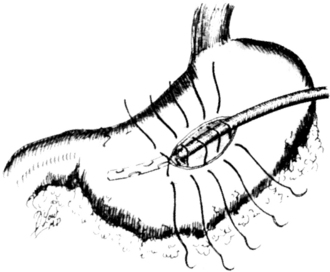

Witzel gastrostomy is created similarly to the Stamm gastrostomy, with the additional construction of a 4- to 6-cm seromuscular tunnel of the stomach wall through which the gastrostomy tube is placed (Figure 39-3). The seromuscular tunnel is designed to reduce the risk of peritubular leakage, particularly when the stomach is distended or the tube is removed.

Janeway gastrostomy.

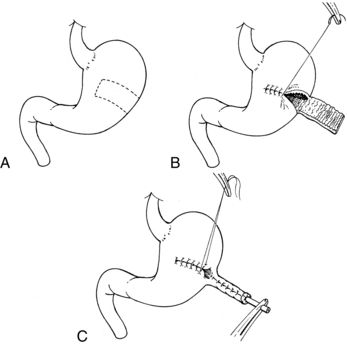

Janeway gastrostomy is a surgically constructed, mucosa-lined gastric passageway that is brought out onto the abdominal surface as a permanent mucocutaneous stoma. Figure 39-4 illustrates how the Janeway gastrostomy is constructed. Postoperatively, an inflated balloon-tip catheter is placed in the tract. Once the tract has matured (7–10 days), the tube is removed. A tube is inserted into the Janeway gastrostomy during each feeding and then removed. This type of permanent gastrostomy requires more operative time than the Stamm gastrostomy and results in many similar complications (Gorman et al, 1995).

Witzel jejunostomy.

The Witzel technique is the most common technique for surgically placed jejunostomy. The Witzel technique can be used to create a jejunostomy either at the conclusion of a surgical procedure or as an isolated procedure. The usual site is the left upper quadrant. A loop of jejunum 15 to 20 cm from the ligament of Treitz is brought up to the wound, and a circular pursestring suture is placed in the antimesenteric border. An incision through the center of the pursestring suture is made, and a 14-French (14Fr) feeding catheter is inserted into the jejunal lumen and advanced. A serosal tunnel is constructed at the exit site in the jejunal wall, extending approximately 5 to 6 cm proximally. The catheter is brought to the skin through a separate incision and secured, typically with sutures. The loop of intestine is anchored to the anterior abdominal wall (Wu and Soper, 2004).

Needle catheter jejunostomy.

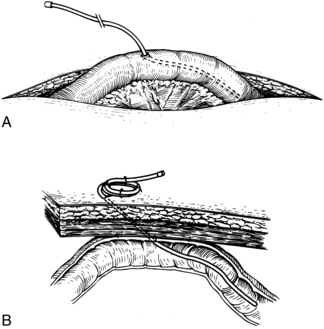

The needle jejunostomy is a simple procedure that is most often done at the conclusion of a surgical procedure when prolonged enteral support is anticipated. At approximately 30 to 40 cm distal to the ligament of Treitz, a 14- to 16-gauge needle is inserted into the jejunal wall. A feeding catheter is advanced through the needle 30 to 40 cm distally, and the needle is withdrawn. A pursestring suture is made around the tube to close the jejunal opening around the catheter. The loop of bowel is anchored to the anterior abdominal wall, and the catheter is secured to the skin (Figure 39-5) (Harbison, 2007).

Laparoscopic surgical approach.

The laparoscopic approach for insertion of the gastrostomy or jejunostomy has been possible since the introduction of high-resolution video cameras and has the advantages of minimal invasion and few surgical side effects (Georgeson, 1997). This approach also provides the opportunity to selectively determine the site of the tube within the stomach (e.g., lesser-curvature gastrostomy rather than the more commonly selected greater-curvature), which may be important in the patient who is at high risk for reflux or aspiration. A key advantage to a laparoscopic approach is that the abdomen can be examined under direct vision without the need for a large surgical incision so that biopsy specimens can be obtained if necessary or malignancy staging can be conducted (Coates and MacFadyen, 1996). This technique requires a smaller incision than the open surgical approach, but local or general anesthesia is still needed.

Laparoscopic gastrostomy.

The indication for laparoscopic gastrostomy for feeding is the inability to perform percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy, such as with a morbidly obese patient. A small supraumbilical incision is made through which the camera port is placed, and a 5-mm port is placed in the epigastrium. An atraumatic instrument is used to grasp the stomach, and the site for the proposed gastrostomy is identified. An 18-gauge angiocatheter is passed through the anterior abdomen, at the site chosen for the gastrostomy, and into the stomach. The needle is removed, and a soft J-wire is passed into the stomach. Dilators (12Fr and 14Fr) are placed over this J-wire. A 16Fr peel-away catheter is placed over the dilator, and a 16-Fr catheter is inserted through the sheath. The catheter is positioned against the stomach wall by inflating the balloon or securing the internal bumper. This particular type of gastrostomy is less commonly used than the Stamm due to technical requirements and pneumoperitoneum (Harbison, 2007).

Laparoscopic jejunostomy.

Specific indications for laparoscopic jejunostomy include concomitant laparoscopy for other problems and difficult laparoscopic gastrostomy. It is a minimally invasive procedure with desirable advantages of reduced postoperative pain and shortened recuperative time; general anesthesia is required. The procedure is more expensive than percutaneous or surgical placement. Two methods described by Wu and Soper (2004) are briefly discussed in this section.

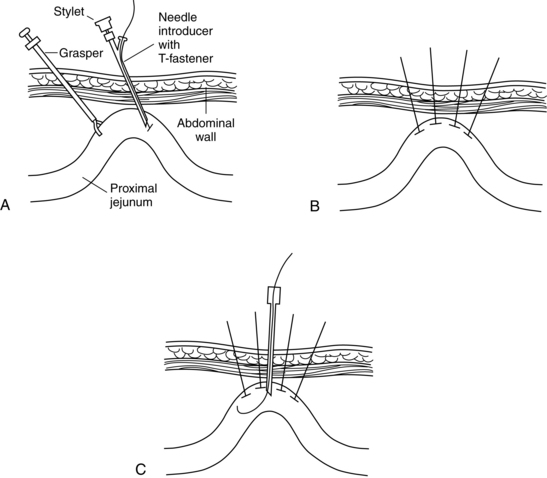

In another technique, T-fasteners (or tacks) are inserted through the skin into the bowel lumen to anchor and retract the bowel against the abdominal wall (Duh and McQuaid, 2000; Wu and Soper 2004). Once the bowel is anchored, a percutaneous jejunostomy tube can be placed directly through the abdominal wall (Figure 39-6).

Endoscopic approach

The endoscopic approach to gastrostomy tube placement, known as percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG), was first described by Gauderer and Ponsky (1980) and has quickly become the procedure of choice. These devices can be placed under local anesthesia and conscious sedation outside the operating room, thus avoiding the complications associated with surgical procedures.

Contraindications to PEG include inability to perform upper endoscopy, inability to illuminate the abdominal wall, ascites, esophageal obstruction, hepatomegaly, previous gastric resection, and uncorrectable coagulopathy (Bankhead and Rolandell, 2005).

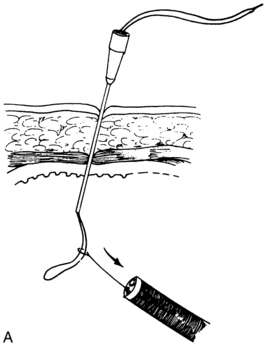

“Pull” (ponsky) technique.

A small incision is made over the illuminated site, and a large-gauge angiocatheter is inserted into the stomach. The needle is withdrawn, and 60 inches of suture is passed through the catheter into the stomach. With a biopsy snare, the endoscopist grasps the suture and pulls so that the endoscope is removed with the suture attached (Figure 39-7). The gastrostomy tube is attached to the suture. By pulling on the suture at the abdominal gastrostomy site, the endoscopist draws the tube through the esophagus into the stomach and positions it snugly against the anterior stomach wall. To verify proper position of the PEG, an endoscope is passed again. Once placement is confirmed, the endoscope is removed, and the PEG secured at the skin level (Harbison, 2007).

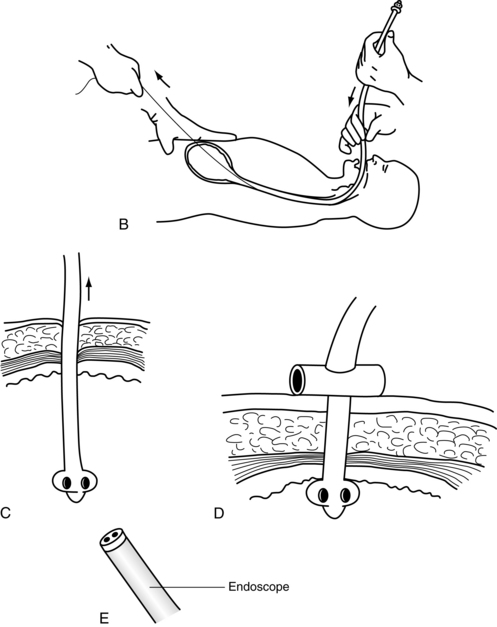

“Over the wire” (sachs-vine) technique.

With this technique, a long, flexible guidewire is inserted through the angiocatheter into the stomach. With use of the biopsy snare and endoscope, the wire is snared and pulled up through the esophagus and out the patient’s mouth (Figure 39-8). The PEG tube is pushed over the guidewire and advanced through the esophagus to the stomach and positioned against the anterior stomach wall. As with the “pull” technique, PEG placement is checked with the endoscope, which is then removed, and the PEG is secured.

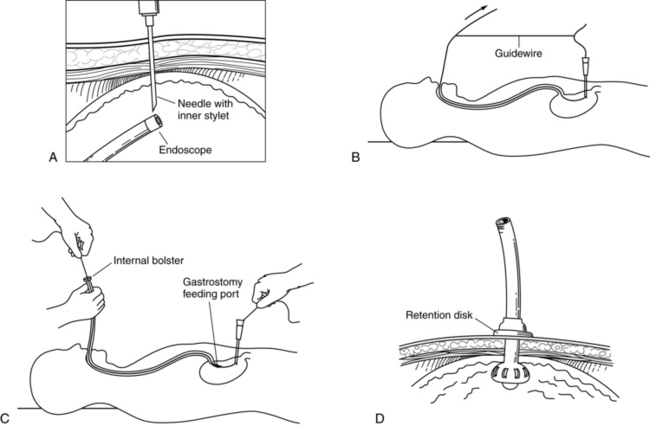

“Push” (russel) technique.

Modifications to the Ponsky or Sachs-Vine technique in which the second passage of the endoscope is obviated have been described. Another technique is a modification of the push technique that involves passing a dilator with a peel-away introducer over the guidewire. The endoscopist confirms the position of the dilator, the dilator is removed, and a well-lubricated catheter is placed through the introducer as the introducer is peeled away. The endoscopist verifies adequate placement of the catheter against the anterior stomach wall, and the endoscope is removed (Bankhead and Rolandell, 2005).

Transpyloric pej.

A small feeding tube with a weighted tip and an attached heavy suture tie are passed through a previously established gastrostomy. Under endoscopic visualization, the suture is grasped with a biopsy forceps, and the suture and attached feeding tube are guided into the duodenum (Figure 39-9). The endoscope is withdrawn. An excess amount of tubing is left within the stomach to allow peristalsis to pull the weighted tip past the ligament of Treitz.

Transpyloric PEJ is associated with considerable long-term complications, including (1) separation of the inner PEJ tube from the outer gastrostomy tube, (2) clogging of the small-diameter PEJ, and (3) kinking of the PEJ. Furthermore, the goal of reduced aspiration pneumonia has not been achieved, possibly as a result of retrograde migration of the tube back into the stomach or impaired pyloric sphincter function triggered by the presence of the tube (Gorman and Morris, 1997).

Directed pej.

Another directed PEJ technique involves a small incision in the upper quadrant. The endoscope is inserted beyond the ligament of Treitz. and the proximal end of the jejunum is clamped. In the small incision, a short segment of jejunum is eviscerated using the Witzel technique. The feeding tube is placed into the jejunum, the jejunum is returned to the abdominal cavity, and the proximal and distal ends of the jejunum are secured to the abdominal wall. The directed PEJ seems to alleviate the problems associated with transpyloric placement (tube migration, clogging, and aspiration). Evidence for the long-term benefits, efficacy, and use of this procedure is inconclusive.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree