Pelvis, Hip, and Upper Leg

David M. Peck

Section A Pelvis and Hip

The pelvis functions as a connection between the trunk and the lower extremities as well as to provide protection to the internal organs (1,2). The hip joint is a deep ball and socket joint in which the functional stability mainly comes from the acetabular labrum shape and three thick capsular ligaments. The three ligaments run in a spiral course from their different sites on the pelvis to the femur (3). They are relaxed during flexion and lateral rotation of the hip joint, which is the position that the hip is most susceptible to dislocation.

Readily palpable landmarks of the pelvis region include the iliac crest with the anterior superior iliac spine and the pubic tubercle, which together are the attachment points of the inguinal ligament, and the posterior superior iliac spine. Four to six inches below this area the ischial tuberosity is palpable. The greater trochanter of the femur forms a bony landmark approximately 4 inches lateral and superior to the ischial tuberosity.

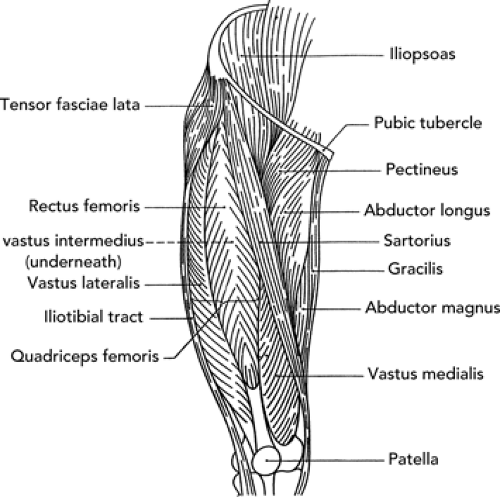

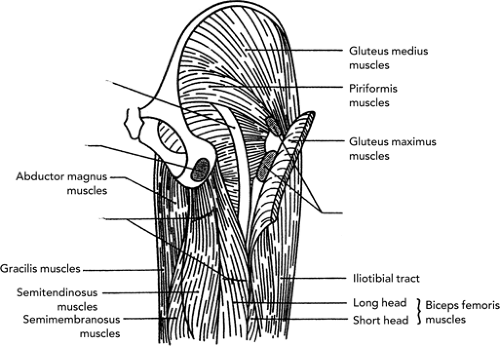

The muscles of the hip and pelvic area function to maintain stability of the weight-bearing joint and to propel the athletes’ body forward (see Figures 30A.1 and 30A.2). The major muscles of the hip and thigh can be grouped by the main motions that they exert on the thigh or lower extremity (3). The abductor muscles are vital to counteract the body weight’s forced adduction in the one-legged stance, which puts them under great force and places them at risk for wear and tear (3). They also function to move the thigh away from the midline. The abductors are made up of the Gluteus medius and minimus and the tensor fascia latae and they insert on the greater trochanter of the femur. The hip flexors are important to initiate the swing phase during ambulating and to pull the thigh towards the trunk (3). They are made up of the iliopsoas, rectus femoris, and to a lesser degree the pectineus and tensor fascia latae. The flexors generally insert on the lesser trochanter of the femur. The adductor muscles move the thigh to the midline and assist in hip flexion in the stance phase. They are made up of the adductor longus, brevis, magnus, the gracilis, and the pectineus, and insert along the medial border of the femur at the linea aspera. The extensors of the hip are the Gluteus maximus, long head of the biceps femoris, semimembranosus, and semitendinosus. They function to prevent hip and trunk flexion during the gait phase of ambulating and are responsible for climbing. The piriformis, superior and inferior gemelli, obturator externus and internus, and quadratus femoris all function as external rotators of the hip. The piriformis muscle is in intimate contact with the sciatic nerve. There are no true internal rotators of the hip, but several sections of hip muscle help in this function such as the anterior fibers of the gluteus minimus.

Three major nerves innervate the hip and the surrounding structures; the sciatic nerve, the femoral nerve, and the obturator nerve, which lie posteriorly, anteriorly, and medially, respectively (4). Knowledge of the muscle actions, locations and their innervations and the soft tissue structures about the hip is essential for proper diagnosis and treatment of most disorders that affect the pelvis and hip. Although this section concentrates on the orthopedic aspects of hip and pelvis disorders, it is paramount for the clinician to rule out other causes of

referred pain such as lumbar disc disease, gastrointestinal and genitourinary disorders, or other nonorthopedic conditions.

referred pain such as lumbar disc disease, gastrointestinal and genitourinary disorders, or other nonorthopedic conditions.

Physical Examination

After taking a thorough history of the hip or thigh problem, a physical examination should be undertaken. The examination should include inspection of the area, with adequate exposure, palpation of the area, assessment of the patient’s gait, and examination of the biomechanics of the foot. Next a thorough neurovascular assessment, and an evaluation of muscle strength and flexibility, as well as a sensory examination should be performed. There are several provocative tests specific for the hip, pelvis, and thigh, and several will be reviewed (5,6).

Trendelenberg Test

With the patient standing, he/she lifts one leg flexing at the hip. The hip of the stance leg should remain level. If the stance hip elevates, the test is positive for abductor weakness. This can be a sign of hip arthritis, slipped capital femoral epiphysis (SCFE), peripheral nerve lesion, or fracture (see Figure 30A.3).

Patrick’s Test

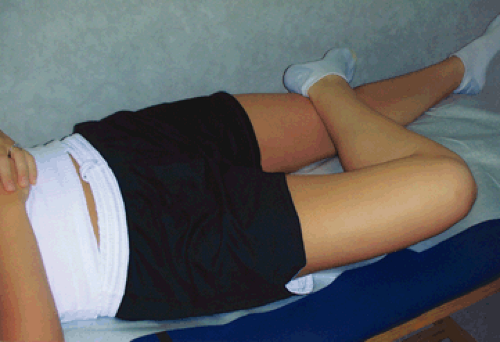

This test is also known as the faber test, which stands for flexion, abduction, and external rotation of the hip. The supine patient is asked to place the ankle of one leg on the opposite knee and externally rotate the bent leg. The inability to maintain this position is positive for either hip joint pathology or sacroiliac dysfunction (see Figure 30A.4).

Thomas Test

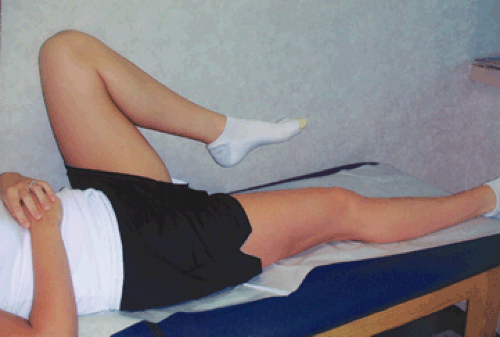

This test assesses the hip flexibility by having the supine patient maximally flex one hip while the opposite hip is maintained in extension. Inability to maintain the contra

lateral knee or hip in extension is a sign of hip flexor contracture (see Figure 30A.5).

lateral knee or hip in extension is a sign of hip flexor contracture (see Figure 30A.5).

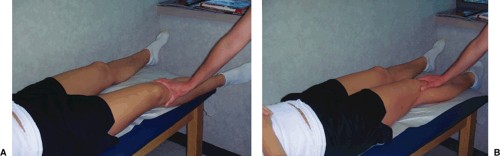

Ober Test

The ober test is a test for iliotibial band (ITB) tightness and is performed with the patient lying on one side. The hip and knee are flexed. The examiner abducts the hip and brings it into neutral. Then the hip is released and if no ITB tightness is present the leg should adduct freely to gravity (see Figure 30A.6).

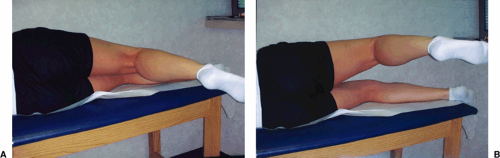

Ely’s Test

The patient is placed in the prone position and the knee is flexed to ninety degrees. The test is positive for rectus femoris tightness if the ipsilateral hip flexes.

It is important to test both legs for all of these tests (see Figure 30A.7).

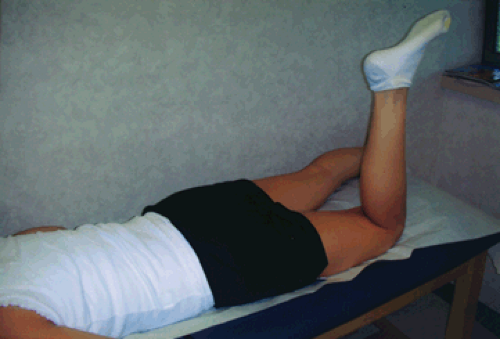

Log Roll Test

The patient is supine and by holding the foot the hip is moved fully from internal rotation and external rotation. Reproduction of pain signifies a possible intra-articular infection, fracture, or synovitis (see Figure 30A.8).

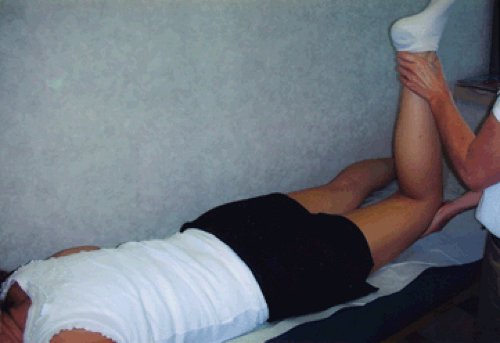

Femoral Nerve Stretch Test

The patient is in the prone position and the knee is flexed to ninety degrees and the ipsilateral hip is extended. Reproduction of pain or numbness in the anterior thigh signifies either lateral femoral nerve dysfunction or nerve root pathology (see Figure 30A.9).

Soft Tissue Contusions

Contusions about the pelvis and hip are some of the most common injuries in athletics, especially in football, ice

hockey, gymnastics, basketball, and volleyball (1,2). Injury is usually caused by contact with another player, another player’s equipment (helmet), or the playing surface (floor, field, or boards) (2). Bony or soft tissue prominences are the most common sites of contusion including the iliac crest (hip pointer), ischial tuberosity, greater trochanter, pubic rami, and sciatic nerve.

hockey, gymnastics, basketball, and volleyball (1,2). Injury is usually caused by contact with another player, another player’s equipment (helmet), or the playing surface (floor, field, or boards) (2). Bony or soft tissue prominences are the most common sites of contusion including the iliac crest (hip pointer), ischial tuberosity, greater trochanter, pubic rami, and sciatic nerve.

The athlete will usually present with localized pain over the area in question, which can progress to loss of range of motion (ROM) and decrease in function. With iliac crest contusion (hip pointer), the athlete may be unable to straighten the trunk or rotate the trunk away from the site. With time, swelling and bruising may develop and in severe cases may lead to prolonged disability such as myositis ossificans (2). A full neuromuscular examination should be performed to rule out a complete avulsion.

Plain film radiological evaluation is essential to rule out an avulsion fracture and should be obtained in at least two planes. Treatment begins with immediate application of ice, compression with a wrap, and rest from painful activities to avoid prolonged disability. An attempt at aspiration of the hematoma may be considered, but the practice has met with limited success (1). Avoidance of heat modalities (hot packs, ultrasound, and electrical stimulation) and vigorous massage should be followed in the first 48 hours to limit the amount of bleeding into the area. Rehabilitation is aimed at maintenance of pain-free ROM, gentle stretching, and progressing to trunk flexion and strengthening for the iliac crest contusion. An injection with 1% to 2% Lidocaine and long acting cortisone into the area of maximal tenderness may shorten the course of the condition, but should be held off until after the acute phase (48 to 72 hours) (2).

Return to play may be considered when the athlete shows full pain-free ROM, full motor function, and ability to perform sports-specific activities without pain (1). The area should be padded with an elongated donut pad underneath any required equipment to prevent recurrence. A common practice to be avoided is altering (cutting part of the pad) or not using the hip pads in contact sports such as ice hockey and football.

Hip Apophysitis

Apophysitis is an inflammation at the site of a major tendinous insertion onto a bony prominence that is undergoing growth (7). Growth is a predisposing factor in this group of injuries in that it leads to muscle–tendon imbalance (inflexibility). This inflexibility combined with repetitive activity leads to this inflammatory condition (8). Apophysitis about the hip occurs at the origin or insertions of some of the major muscle groups including the iliac crest, (abdominal muscles) the ischial tuberosity (hamstring muscles), the anterior superior iliac spine (sartorius muscle), the anterior inferior iliac spine (quadriceps muscle), the lesser trochanter (iliopsoas muscle), and the greater trochanter (gluteus medius and minimus) (see Figure 30A.10). This condition can occur until the growth centers completely ossify. The following is a list of the relative ages of fusion of the apophyses: iliac crest (15 to 17 years),

ischial tuberosity (19 to 25 years), anterior superior iliac spine (21 to 25 years), anterior inferior iliac spine (16 to 18 years), lesser trochanter (16 to 18 years), and the greater trochanter (16 to 18 years) (1).

ischial tuberosity (19 to 25 years), anterior superior iliac spine (21 to 25 years), anterior inferior iliac spine (16 to 18 years), lesser trochanter (16 to 18 years), and the greater trochanter (16 to 18 years) (1).

Iliac crest apophysitis is the most common of this group of injuries and usually presents with anterior and superior hip pain with activity. The iliac crest ossification center closes between the ages 16 and 20 in males and 14 and 18 in females and closes from anterior to posterior. Long distance runners and dancers often develop this condition. On examination, the athlete may have tenderness over the anterior half of the iliac crest and pain may be reproduced with hip abduction against resistance or trunk rotation. Plain film x-rays should be ordered to rule out an avulsion fracture.

Apophysitis about the hip, as with all apophysitis’, has a very favorable prognosis and usually responds to a conservative treatment program (7). The mainstay of treatment is relative rest from pain-producing activities. The athlete may participate in his/her activity at a level that does not induce pain. In some cases, the athlete must rest from all activities and in rare cases must crutch-walk until pain-free. Rest, ice application, anti-inflammatory medications, and cross training are followed by a slow progression of activities over a 4- to 6-week period. An aggressive program of abdominal and hip flexibility is essential for return to pain-free activity.

Osteitis Pubis

Osteitis pubis in the athlete is a cause of chronic groin pain usually seen in distance runners, weight lifters, fencers, football, soccer, and basketball players (2,6). There are several etiologies for this condition including acute trauma to the area, but it is generally felt to be caused by repetitive trauma to the pubic symphysis from muscle strain of the gracilis or abdominal muscles. This sets up an inflammatory response. It has been postulated that this pathophysiology is similar to that seen in shin splint syndrome (2).

The athlete will usually complain of a slow insidious onset of dull groin pain which becomes worse with activity and which can be chronic and incapacitating. The pain may radiate into the lower abdomen, proximal medial thigh or inguinal area and is relieved by rest. The patient walks with an antalgic or waddling gait. Tenderness to palpation over the pubic tubercle and pubic symphysis is noted. Pain may be noted over the pubic symphysis on passive abduction or adduction against resistance. On examination, a one-legged hop test may reproduce the groin pain.

X-rays are important to rule out avulsion fractures, unstable symphysis, or other bony pathology. Radiographic changes can lag 2 to 4 weeks behind the Clinical findings. Harris and Murray studied 38 patients with osteitis pubis and found three characteristic findings on x-rays: (a) symmetrical bone resorption in the medial ends of the pubic bone, (b) widening of the pubic symphysis, (c) rarefaction or sclerosis along the pubic ramus (9). Bone scan shows diffuse uptake early in the course of the condition.

This condition is generally self-limited; hence rest from painful activity is the mainstay of treatment. Anti-inflammatory medications and modalities may speed the healing process, but it may take from 2 to 3 months up to 2 years. Cross training with swimming or other partial weight-bearing activities to maintain cardiovascular fitness can be performed. Severe cases of osteitis pubis may require a trial of cortisone injections. Chronic cases that don’t respond to an exhaustive trial of conservative therapy may need surgical debridement and arthrodesis of the pubic symphysis.

Avulsion Fractures of the Hip and Pelvis

Avulsion fractures of the hip and pelvis occur in the skeletally immature athlete, especially Tanner stage 3, when the relatively weak apophysis is subjected to a sudden violent contraction of one of the large muscle groups that attach here (10). Sprinters, jumpers, soccer players, gymnasts, dancers, and football players are at risk for this type of injury and this type of fracture accounts for 11% to 40% of all hip and pelvis fractures in children. The sites involved are as follows: (a) ischial tuberosity—hamstring muscles, (b) anterior inferior iliac spine—rectus femoris muscle, (c) anterior superior iliac spine—sartorius muscle, (d) iliac crest—abdominal muscles, (e) lesser trochanter of femur—iliopsoas muscle, and (f) greater trochanter of femur—gluteus medius and minimus (6,10

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree