9.1 Introduction

The pelvis is a closed ring of bone formed by the two innominate bones and the sacrum. The pelvis transmits the forces acting on the spinal column to the lower extremities and protects the pelvic organs. Parts of the proximal pelvic ring provide insertions for the musculature of the trunk, and parts of the hip and thigh musculature insert into its distal parts. Therefore, evaluation of any pelvic pathology should also include examination of the spine and lower extremities.

Degenerative changes lead to chronic irritation of the pubic symphysis and sacroiliac joints. Unbalanced stresses resulting from deficient posture can produce arthritic changes in the sacroiliac joint. Predisposing factors include scoliosis and leg-length difference.

Sacroiliac dysfunction is a disturbance of the motion at the sacroiliac joint.

The sacroiliac joint is also frequently involved in rheumatic disorders. Table 9.1 provides an overview of types of sacroiliac arthritis.

Pelvic trauma can involve soft-tissue damage or bone injuries. Bone injuries include pelvic rim fractures (such as an avulsion fracture of the anterior superior iliac spine), fractures of the pelvic ring, and acetabular fractures.

Pelvic ring fractures are divided into three categories according to the condition of the posterior segment of the ring, which is crucial for the biomechanical stability of the pelvis (Table 9.2):

• stable (type A injuries);

• rotationally unstable (type B injuries);

• rotationally and vertically unstable (type C injuries).

There is no universally accepted classification system for pelvic ring fractures. Table 9.2 shows the 1991 version ofthe AO/ASIF classification system as proposed by Pennal etal. (1980). Since then, the AO/ASIF system has undergone further revision. The 1995 version is a combined classification ofthe anterior and posterior pelvic ring. It is designed as an open system, which enables it to encompass a wide variety of pelvic ring injuries and permit precise scientific documentation. The classification of pelvic fractures is in evolution and the literature should be reviewed for more detailed information.

| Disorder | Characteristics/symptoms | HLAtype |

| Ankylosingspondylitis | Initial manifestation often in the sacroiliacjoint | HLA-B27 |

| Reiter syndrome | At least two joints are involved with at least one of the following symptoms: urethritis, cervicitis, conjunctivitis, or Shigella dysentery | HLA-B27in80%ofallcases |

| Psoriatic arthritis | Frequently associated with joint and fingernail symptoms (stippling, nail grooves, or nail loosening) | Often HLA-B27 and occasionally HLA-Bw38 |

| Whipple disease | Inflammation of the sacroiliacjoints as in ankylosing spondylitis | |

| Bowel disorders (Crohn disease, ulcerated colitis) with involvement of the sacroiliac joint | Joint involvement is more frequent when the colon is involved | HLA-B27 positive in 70% of all cases |

| Rheumatic arthritis | Sacroiliacjoints are less frequently affected, usually unilaterally | HLA-Dw4 and HLA-DR4 |

| Sjögren syndrome | Triad: dry eyes, dry mouth, HI_A-Dw3 and arthritis; primarily (90%) in middle-aged women | HLAOw3 |

| Associatedarthritis | In infections (bowel or urogenital tract) caused by Yersinia, salmonella, orgonococci | Frequently HLA-B27 positive |

| Type | Lesion | |||

| A | Stable | |||

| A1 | Fractures without involvement of the pelvic ring (avulsion fractures) | |||

| A2 | Fractures of the iliac wing without involvement of the pelvic ring | |||

| Pelvic ring fractures without (significant) displacement | ||||

| A3 | Transverse fractures of the sacrum and coccyx without involvement of the pelvic ring | |||

| B | Rotationally unstable, vertically stable | |||

| B1 | External rotation injury (open book), i.e., rupture of the pubic symphysis | |||

| B2 | Compression injury with internal rotation deformity of one half of the pelvis | |||

| B2.1 | Ipsilateral type | |||

| B2.2 | Contra lateral type | |||

| B3 | Bilateral type B injuries | |||

| C | Rotationally and vertically unstable (vertical shear) | |||

| C1 | Unilateral | |||

| C1.1 | Fracture of the ilium | |||

| C1.2 | Rupture or fracture dislocation ofthe sacroiliac joint | |||

| C1.3 | Fracture of the sacrum | |||

| C2 | Bilateral incomplete | |||

| C3 | Bilateral complete | |||

| C lesion with additional acetabularfracture | ||||

An example of a rotationally unstable pelvic ring injury (i.e., unstable in the horizontal plane) is an isolated rupture of the pubic symphysis caused by an anteroposterior (AP) force in which the anterior ligaments of one or both sacroiliac joints are also torn. Vertical stability of the pelvis is not compromised because the crucial biomechanical posterior ligament connections remain intact. However, shear forces will produce a rotationally and vertically unstable injury (the classic Malgaigne fracture), such as can occur when landing on one leg after a fall from a height.

The system developed by Letournel and Judet (1993) has become the standard for classifying acetabular fractures. The acetabulum is divided into anterior (iliopubic) and posterior (ilioischial) columns. For each of these locally, basic forms of fractures (fracture ofthe acetabular rim, column fracture, and transverse fracture) are distinguished from combined fracture forms, such as a fracture of both columns. This classification was modified by the AO/ASIF according to Table 9.3.

The incidence of pelvic fractures varies between 3% and 10%, depending on the author and patient group. Automobile accidents are cited as the most frequent cause, accounting for 80-90% of all injuries. This is followed by falls from a great height and crush injuries. Injuries to the pelvis and hip represent a relatively insignificant number of athletic injuries, accounting for 2-3% of these injuries. Fatigue fractures in the hip and pelvis are also relatively rare; only about 3% of all fatigue fractures occur as the result of athletic activity.

Pelvic injuries can be categorized according to their cause as extrinsic (externally caused) and intrinsic injuries. The latter are due to forces acting within the body itself and include such injuries as avulsion fractures or muscle tears. In addition to the classic cases of sudden trauma, stress in the form of chronic improper use or overuse can also cause injuries. Examples of this are the rare stress fractures of the pubic bone that can occur in joggers.

Extrinsic soft-tissue injuries include skin abrasions (frequently superficial) and crush injuries at structures such as the iliac crest where the bone is only covered by a thin layer of soft tissue. Blunt trauma in the lateral and posterior pelvis can result in extensive compression ofthe surrounding muscle layers. These injuries may present as broad hematomas (Table 9.4).

| Type A | Involvement of only one column of the acetabulum while the second column is intact |

| A1 | Fractures of the posterior acetabular rim with variants |

| A2 | Fractures of the posterior column with variants |

| A3 | Fractures of the anterior acetabular rim and the anterior column |

| Type B | Characterized by a transverse fracture component whereby at least a portion of the acetabular roof is intact and must remain in contact with the ilium |

| B1 | Transverse fractures through the acetabulum with or without a fracture of the posterior rim of the acetabulum |

| B2 | T-shaped fractures with variants |

| B3 | Fractures of the anterior column of acetabular rim associated with a posterior “hemi-transverse” fracture |

| Type C | Fractures of both columns: the fracture lines course through both the anterior and posterior columns. In contrast to type B fractures, all articular fragments including the acetabular roof are separated from the rest of the ilium |

| C1 | Fracture of the anterior column coursing as far as the iliac crest |

| C2 | Fracture of the anterior column coursing into the anterior margin of the ilium |

| C3 | Transverse fractures extending into the sacroiliac joint |

| Extrinsic | Intrinsic |

| Contusions, crush | Muscle pulls and small tears in |

| injuries, skin abrasions | the muscles inserting into the |

| (for example at | pelvis, such as the adductors, |

| the iliac crest), | rectus femoris, iliopsoas, |

| hematomas in the | abdominal oblique muscles, and |

| gluteal region | rectus abdominis |

Intrinsic soft-tissue injuries include the numerous types of muscle pulls and tears. Injuries to the adductors are common. Injuries to the proximal portion of the rectus femoris are also observed. In rare cases, tears in the insertions of the iliopsoas can also occur. Minor tears can also occur in the abdominal oblique muscles at the iliac crest, and in the rectus abdominis in the region of the pubic bone (Table 9.4).

The group of extrinsic bone injuries includes traumatic damage to the pubic bone, ischium, sacrum, or coccyx. Extreme trauma can also disrupt the pelvic ring. These injuries are often complicated by associated injuries to neurovascular structures, the urethra, or the bowels (complex pelvic trauma). Less severe injuries of this type include fractures of the coccyx (Table 9.5).

Intrinsic bone injuries (avulsion fractures) are caused by muscular traction on the origin of the apophysis. They frequently occur in teenagers and young adults and primarily involve the anterior superior and anterior inferior iliac spines, the pubic bone, and, rarely, the iliac crest and ischial tuberosity (Table 9.5).

Overuse fractures can also be included among the intrinsic bone injuries. Sites include the pubic bone and, rarely, the ischium and sacrum.

The pelvis may be involved in systemic disorders. These include disturbed calcium and phosphate metabolism that may result from vitamin D deficiency, primary hyperparathyroidism, or renal dysfunction, which itself can lead to secondary hyperparathyroidism. Sequelae of these metabolic changes observed in the pelvic bones include osteomalacia with softening of the bone and structural insufficiency. In children for example, chronic vitamin D deficiency leads to flattening of the pelvis typical of rickets.

| Extrinsic | Intrinsic |

| Fractures | Avulsion fractures |

| These may be caused by direct external trauma, for example fractures of the pelvic ring due to extreme trauma such as a riding or motorcycle accident | The cause is uncoordinated powerful muscular traction on the origin of the apophysis, usually in the second decade of life. Predisposed sites include the anterior superior and anterior inferior iliac spines, pubic bone, and (rarely) the iliac crest and ischial tuberosity Stress fractures |

| The cause is chronic overuse. Predisposed sites: pubic bone, less frequently the coccyx and sacrum | |

| Other overuse injuries | |

| Arthritis in the sacroiliac joints |

Another systemic skeletal disorder primarily affecting the pelvis in older patients is Paget disease (osteitis deformans). The cause of this disorder is unclear. Symptoms include “rheumatic” symptoms, spontaneous fractures, and skeletal deformations.

Finally, there are inflammatory disorders (such as osteomyelitis) and tumors. Tumors are often metastatic in origin. Osteoblastic metastases proceed from prostate and breast carcinomas. Osteolytic metastases generally stem from bronchial, thyroid, and kidney carcinomas, occasionally from breast carcinomas. Primary tumors in the pelvic region include chondrosarcomas and Ewing sarcomas.

9.2 Clinical Standard Examination

Since the pelvis is the bridge between the spine and the lower extremities, the history and examination of pelvic symptoms should also include the history and examination of the spine and lower extremities, particularly the hip.

Physical examination of the pelvis begins with inspection. In addition to observation of the morphology of the pelvis, include evaluation of gait. Palpation includes the muscular insertions and important bony structures such as the anterior and posterior iliac spines, the pubic symphysis, and the joints. Always examine pelvic version, and document any pathologic anterior movement of the posterior iliac spines indicative of limited motion in the sacroiliac joints when the patient bends over. This is followed by examination of the sacroiliac joints in particular, and by functional testing of the muscles of the pelvic girdle.

The final phase of the pelvic examination consists of neurovascular examination of the lower extremities and of the genitals where pelvic trauma is present.

The tentative diagnosis reached on the basis of clinical examination can be verified or modified by subsequent diagnostic imaging studies (Table 9.6).

| • History |

| • Inspection |

| • Palpation |

| • Neurovascular examination |

| • Diagnostic imaging studies |

Patient History

Interpreting information from the history is difficult in the presence of pelvic symptoms, particularly where there are atypical chronic symptoms such as groin pain or “diffuse” pelvic pain. The patient should be routinely asked the following questions:

• How long have the symptoms been present and under what conditions did they first occur?

Sudden symptoms in the sacroiliac region that occur with body motion are a sign of sacroiliac joint dysfunction.

• Does the pain occur at rest or during exercise?

What stresses is the patient subjected to?

Irritation of the adductors and iliopsoas in particular can decrease or disappear during exercise. Frequently it can reappear with increased intensity after exercise. Persistent groin pain radiating into the buttocks or thigh can occur following strenuous exertion, for example in distance runners. Groin pain can be a sign of a stress fracture of the ischium, pubic bone, or proximal femur. These fractures are most often encountered in female runners; the history should always include sports activities.

• Does the pain occur independently of exercise?

Does it disturb the patient’s sleep?

Pain occurring independently of exercise or which disturbs the patient’s sleep always suggest a disorder other than trauma or overuse, such as appendicitis, prostatitis, urinary tract infection, kidney disorders, gynecologic disorders, osteomyelitis, or tumors in the pelvis or groin region.

• What is the nature of the pain?

Intermittent episodes of dull pain in the sacrum or lower lumbar region occurring primarily in the morning suggest rheumatic disorders, primarily anky losing spondylitis. If the patient reports these symptoms, you should inquire about pain in other parts of the body, particularly in the joints.

• Where is the pain localized? To where does it radiate?

It is important to determine whether referred pain can be linked to a certain dermatome or area of distribution of a peripheral nerve. The differential diagnosis should consider pathology in the lumbar spine. Nerve roots L1 through S5 are responsible for the sensory supply of the lower extremities, buttocks, and genitals (see Fig.8.40b, p. 311).

Obtaining a history with acute injuries to the pelvis is usually easier. Pelvic injury in an accident usually requires trauma involving significant kinetic energy. The patient will often have multiple trauma so that reconstructing the mechanism of injury will require information from other sources. The patient’s age is significant because the same pelvic injuries may require far less trauma in older patients than in younger patients because of osteoporosis. The risk of associated pelvic and extrapelvic injuries in older patients is higher. Ask patients who are conscious and responsive about blood in the urine or perianal bleeding. These can be important signs of associated injuries to the urogenital system or the bowel. Always inquire about disturbed sensation and/or paralysis in the lower extremities. This can be a sign of injury to the femoral, sciatic, or obturator nerves, or the lumbosacral nerve plexus.

Describing the mechanism of injury (crush injury, fall, or automobile accident) including the direction of forces acting on the pelvis is important for diagnosing acute injuries of soft tissue and bone. In adductor tears or avulsions in the region of the pubic bone, the patient will feel a stabbing pain in the groin at the moment of injury. Adducting the legs will be painful. Adductor tears typically occur with abrupt excessive abduction. Sports such as soccer, ice hockey, skiing, and hurdle events entail an increased risk of these injuries. Such injuries can occur in everyday situations where the patient attempts to avoid a fall. Less frequent causes of avulsion fractures include electrical accidents and tetanus.

The abdominal muscles that insert into the pelvis on the pubic bone (especially the rectus abdominis) are especially prone to tear in overuse injuries from weight lifting, gymnastics, crew, and wrestling.

Physical examination

Observation

Observation of the pelvis begins when the patient enters the examining room. Gait irregularities may be due to:

– pain (Duchenne gait);

– muscular weakness (Trendelenburg sign);

– leg shortening (compensatory limp);

– arthrodesis of the hip (compensation for a fused joint).

In the antalgic gait (Duchenne’s gait), the patient attempts to reduce stress on the painful hip by reducing the stance phase of the affected leg in a typically truncated gait, or by shifting the upper body, and thus the body’s center of gravity, over the affectedjoint in the stance phase.

In the Trendelenburg gait, weakness of the hip abductors causes the pelvis to dip toward the unaffected side in the stance phase, and the patient shifts the upper body over the affected side (see Figs.8.19a, b, p. 302). The stance phase is not as sharply truncated as in an antalgic gait. Bilateral insufficiency of the gluteal musculature produces a typical waddling gait.

In a compensatory limp with leg shortening, the upper body is shifted slightly over the leg in the stance phase. Otherwise, the gait is relatively smooth.

In a gait that attempts to compensate for hip fusion, the increased tilt of the pelvis in the sagittal plane, as it moves from hyperlordosis into lumbar kyphosis, produces femoral anteversion in the swing phase.

For a complete examination, the patient should undress completely (seriously injured patients should be undressed). You should observe the undressing as closely as possible because it can provide important information about possible limited motion in the lumbar and sacral spine and/or painful motion, for example in hip flexion. Evaluate the gait again after the patient has undressed.

Document any skin changes such as external signs of injury (scrapes, contusions, or hematomas), discoloration (for example erythema as a sign of inflammation), congenital skin changes, swelling, penetration, and the position of skin folds. The patient’s underwear may contain residual secretions indicative of associated injuries with pelvic fractures, such is bleeding from the anus and/or urethra.

When inspecting the patient from the front, note the position ofthe anterior iliac spines. Normally they should be at the same level. Deviation can be a sign of pelvic obliquity or a difference in leg length.

Observing the pelvis from the side will give you an impression ofthe inclination ofthe pelvis. Lack of normal lumbar lordosis can be a sign of a spasm in the paravertebral musculature. Hyperlordosis or increased anterior pelvic version can be a sign of insufficiency of the abdominal musculature, of a weakness in the extensors, or of a flexion contracture in the hips.

Observe the contour of the musculature of the buttocks on the posterior aspect ofthe pelvis. Asymmetry in the marginal skin folds can be due to diseases of the hip (developmentally dislocated hip), neuromuscular diseases, or leg-length differences. Patients who are not excessively obese will have two small depressions (“sacral dimples”) superior to the posterior iliac spines (Fig. 8.7, p. 297). Deviation of one of these depressions from horizontal is a sign of pelvic obliquity.

A leg-length difference in trauma patients can be a sign of an unstable injury of the pelvic ring with superior displacement of one hemipelvis, or an ace-tabular fracture with central dislocation ofthe hip.

Palpation and Examination

Palpation may be performed with the patient standing or supine. This will depend on the pattern of injury and the degree to which the patient is impaired.

Both sides should be palpated simultaneously if possible. This provides information about differences in skin temperature or unilateral swelling.

• Examination with the patient standing

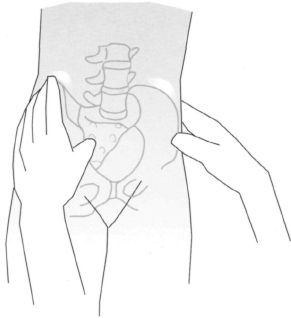

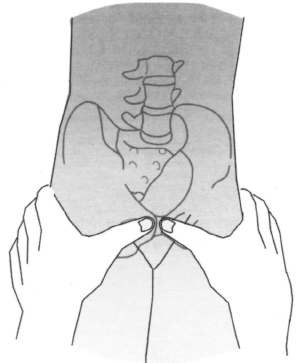

When examining the patient from the front, rest both hands on the patient’s waist with your thumbs on the patient’s iliac spines. Place your fingers on the anterior iliac crest. Compare both sides, and note any pelvic obliquity (Fig. 9.1).

Fig. 9.1 Observation and palpation of the position of the anterior pelvis with the patient standing.

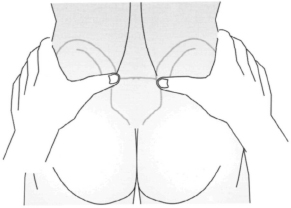

Fig. 9.2 Observation and palpation of the position of the posterior pelvis with the patient standing.

To evaluate the position of the pelvis from behind with the patient standing, place your thumbs on the patient’s posterior superior iliac spines. Move your index finger from lateral across the iliac crests (see p. 301). This may be difficult in obese patients. Normally the anterior and posterior iliac spines and the iliac crests will be at the same level (Fig. 9.2).

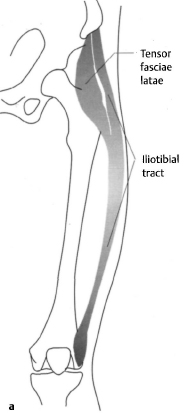

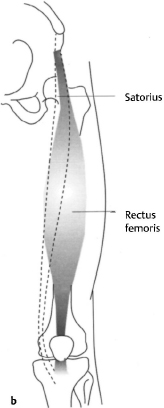

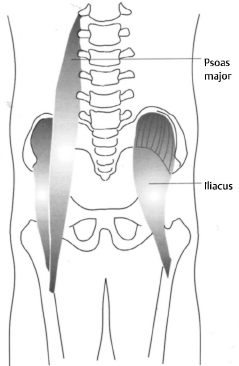

Figs. 9.3a-c

(a) Tensor fasciae latae and iliotibial tract.

(b) Sartorius in relation to the rectus femoris.

(c) Psoas major and iliacus, which together form the iliopsoas.

• Examination with the patient supine

Muscular insertions can be palpated with the patient supine. The tensor fasciae latae is located lateral to the anterior superior iliac spine (Fig. 9.3a). The origin of the sartorius is palpable anteriorly (Fig. 9.3b). Tenderness to palpation in these regions suggests tenosynovitis at the muscular insertions or an avulsion fracture. The iliopsoas, consisting of the iliacus andpsoas, is located medially. (Fig. 9.3c). The iliacus is palpable in the lateral inguinal canal; the psoas can be palpated through the abdominal wall next to the rectus abdominis. Have the patient flex his or her legs to relax the abdominal wall. This will make it easier to palpate the psoas. Overexertion from lifting weights with simultaneous deep knee bends or intensive kicking practice in football or soccer can produce irritation of the psoas that presents as tenderness to palpation. A tear or bursitis of the insertion of the iliopsoas produces tenderness to palpation at its insertion on the lesser trochanter. The anterior inferior iliac spine lies inferior to the anterior superior iliac spine. This is where the rectus femoris has its origin (Fig. 9.3b). It can also be irritated by overuse (for example in kicking practice, frequent sprinter starts, or weight training), torn, or even injured in an apophyseal fracture or avulsion fracture. Apophyseal fractures most frequently occur in adolescent athletes. An unrecognized fracture or malunion can result in thickened callus that can simulate a tumor. In relatively rare cases, this in turn can produce local pain or compressive neuropathy in what is referred to as entrapment syndrome.

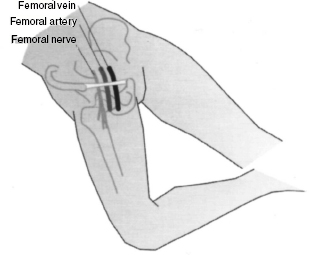

Fig. 9.4 Position of the hip in relation to the most important neurovascular structures in the groin.

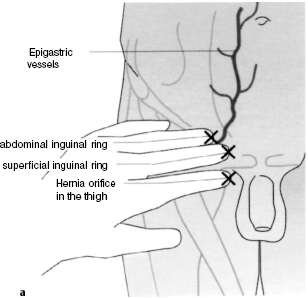

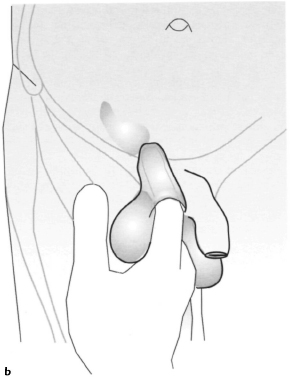

The hip lies at the intersection of the inguinal ligament and the femoral artery (Fig. 9.4). It is not directly accessible to palpation. Tenderness in this region may be regarded as a sign of hip pathology. Swelling proximal to the inguinal ligament suggests an inguinal hernia; swelling distal to it may be a sign of a femoral hernia. Examination of the hernial orifices (Fig. 9.5a) and palpation of the inguinal canal (Fig. 9.5b) with the patient standing or supine is indicated whenever swelling is present. The differential diagnosis should exclude swelling of an inguinal lymph node. Exploration of the inguinal region includes palpation of the femoral artery. Its pulse is normally palpable midway between the anterior superior iliac spine and the pubic tubercle. A weakened pulse in trauma patients can be a sign of vascular injury.

Figs. 9.5a, b

(a) Location of the three different hernial orifices in the right groin.

(b) Palpation of the inguinal canal with the patient standing or supine. Instruct the patient to bear down or cough after you insert your finger.

Fig. 9.6 Palpation of the pubic symphysis and the pubic tubercle with the patient standing.

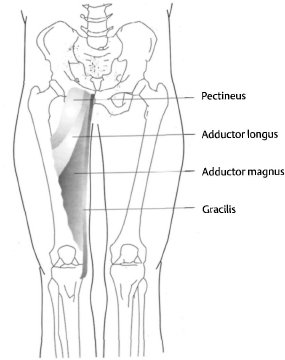

Fig. 9.7 Positions of the various hip adductors relative to each other.

The pubic symphysis or the pubic tubercle can be palpated anteriorly at the level of the trochanters with the patient supine or standing (Fig. 9.6). Note whether the two pubic tubercles are level with each other. Displacement can occur in a rupture of the pubic symphysis. Physiologic painful loosening occurs during pregnancy. Since the rectus abdominis also inserts here, the area will be tender to palpation when the muscle is irritated. Another cause of pain can be inflammation of the pubic symphysis. This is most often due to overuse, but can also be caused by infection. The pectineus inserts lateral to the pubic tubercle; the adductor longus and brevis insert inferior to it (Fig. 9.7). Tears in these muscles produce significant swelling inferior to the pubic bone from the contracted muscle belly and often a hematoma; they also leave a depression at the pubic bone.

Important examination sites on the posterior pelvis in the lateral position and prone position include the ischial tuberosity, sacroiliac joint, posterior hip musculature, sacrum, and coccyx.

The ischial tuberosity is located approximately at the level of the gluteal folds. It is the origin of the hamstrings, which include the semitendinosus, semimembranosus, and long head of the biceps femoris (Fig. 9.8

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree