Pelvic Fractures: External Fixation

Enes M. Kanlic

Amr A. Abdelgawad

INTRODUCTION

Injuries to the pelvic ring range from simple stable fractures as the result of low-energy forces to life-threatening injuries with hemodynamic instability. Pelvic fractures account for 3% to 8% of all fractures seen in the emergency room but are present in up to 25% of multiply injured patients. Mechanically unstable pelvic fractures with hemodynamic instability represent approximately 10% of the pelvic injuries in level I trauma centers. Bleeding from cancellous bone surfaces, the presacral venous plexus, or the arterial tree may cause hypotension and shock. Associated injuries to the chest (15%), abdomen (32%), or long bone fractures can cause additional bleeding in 40% of patients. Prolonged bleeding and shock with massive transfusions are the main cause of multiple organ failure. Early diagnosis with control of hemorrhage is a critical factor in patient survival. Exsanguinating hemorrhage is the main cause of death in the first 24 hours after a high-energy pelvic fracture in a multiply injured patient. Injury severity score (ISS) correlates with whole body injury and is a better predictor of mortality in polytraumatized patients with a pelvic injury than the specific type of pelvic fracture (1, 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6).

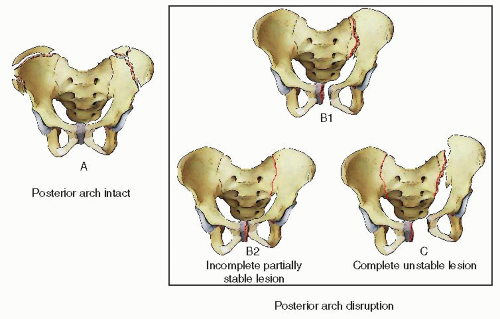

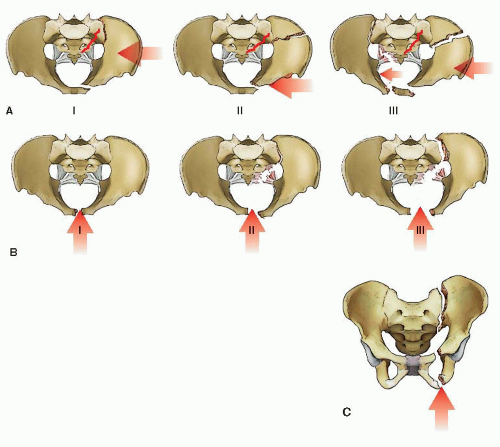

Of the several classification schemes for pelvic fractures, we favor the Tile classification (Fig. 37.1), which is used to predict instability in the injured pelvic ring. Tile A injuries are stable fractures that can be managed nonoperatively. Tile B injuries are rotationally unstable but vertically stable, and Tile C injuries are both rotationally and vertically unstable (7). The Young and Burgess classification of pelvic fractures is also helpful and widely utilized (Fig. 37.2).

INDICATIONS AND CONTRAINDICATIONS

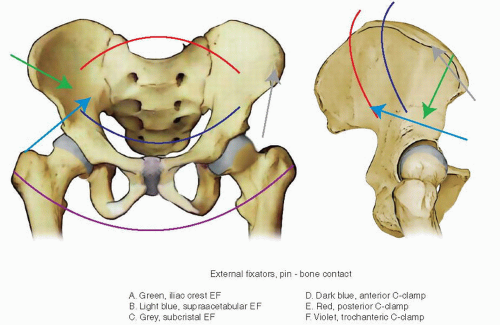

External fixation is utilized primarily in the management of patients with hemodynamic instability following pelvic fractures. The most common indication for external fixation is in a critically ill, unstable patient with a translationally unstable pelvic injury (Tile C). A resuscitative anterior frame with ipsilateral supracondylar traction is used when a C-clamp is unavailable or not applicable. Other indications for anterior external fixation include some, rotationally unstable, Tile B1 and B2 pelvic fractures. We favor external fixation when the soft tissues in and around the pelvis or abdomen are contaminated, such as with open fractures, diverting colostomies or when a suprapubic urinary catheter must be placed. In addition, patients with concomitant visceral injuries, especially injuries that could become more displaced or unstable when the abdomen is opened, are often treated with pelvic external fixation as well. Lately, anterior-ring subcutaneous anterior external fixation (SAEF) is used more often to augment posterior-ring fixation.

Contraindications to external fixation are stable pelvic-ring injuries (Tile A) or compromised soft tissues at planned sites of pin insertion. External fixation should be avoided when internal fixation can be performed on a stable patient in a safe and timely fashion.

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

Patient Stabilization

In the field or emergency room, paramedics and primary responders trained in advanced trauma life support (ATLS) play a critical role. A single attempt at reduction should be considered in patients with hemodynamic instability and a potentially unstable pelvic-ring injury. Traction is applied to the lower extremity on the shortened

or deformed side of the pelvis with manual lateral compression on the iliac wings or greater trochanters. The knees and ankles should be slightly flexed, internally rotated, and taped together, and the pelvis is supported with a wrapped sheet or pelvic binder (Fig. 37.3). These measures may be life-saving when done at the scene of an accident and followed by emergent transfer to an institution capable of treating pelvic trauma (8,9).

or deformed side of the pelvis with manual lateral compression on the iliac wings or greater trochanters. The knees and ankles should be slightly flexed, internally rotated, and taped together, and the pelvis is supported with a wrapped sheet or pelvic binder (Fig. 37.3). These measures may be life-saving when done at the scene of an accident and followed by emergent transfer to an institution capable of treating pelvic trauma (8,9).

Hemodynamically unstable patients with pelvic-ring injuries require prompt evaluation and simultaneous aggressive resuscitation. Initial measures include airway control and fluid resuscitation with 2 L of crystalloid through two 14- to 16-gauge intravenous catheters in the upper extremities if there are no contraindications. If the patient remains hypotensive, packed red blood cells, fresh frozen plasma, and platelets ideally in a 1:1:1 ratio are started. Early transfusion of platelets as six packs to keep platelet counts above 100,000/µL has been shown to improve survival. Patients should be kept warm during diagnostic and therapeutic measures (6,10).

History and Physical Examination

Whenever possible, a careful history should be obtained with particular emphasis on the mechanism of injury. A history of high-energy trauma from motor vehicle or motorcycle collisions, falls from a height, or rollover motor-vehicle crashes is often associated with an unstable pelvic injury. The physical examination should be directed to look for signs of mechanical instability of the pelvis. Clinical signs of instability include a shortened and malrotated extremity, asymmetric iliac spines, swelling or blood around the genitals and perineum, and contusion or ecchymosis in the lower abdomen or pelvis. Gentle, manual, iliac-wing compression from lateral toward the midline may reveal a mobile hemipelvis and mechanical instability. However, stressing the pelvic ring for stability manually by multiple physicians is not warranted because it could dislodge early fragile blood clots in a hemodynamically unstable patient. One-time manual testing, to exclude a situation in which the pelvis had been unstable but has since been reduced, may be permissible by an experienced surgeon in cases where the x-rays are equivocal (11,12). A neurological examination must assess the lower extremity for sensation and motor function in the conscious and cooperative patient. If this is not possible, the physician should note whether there is any movement in the extremities to painful stimuli. Vaginal and rectal exams with testing for occult blood may help rule out an occult open fracture. If overlooked and not treated, a fracture hematoma that comes in contact with a contaminated environment may cause a life-threatening pelvic infection.

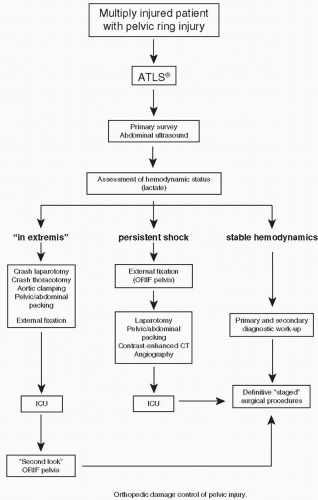

The care of a hemodynamically unstable patient with a displaced pelvic fracture is the responsibility of a multidisciplinary trauma team that includes a general (trauma) surgeon, orthopedic surgeon, interventional radiologist, and anesthesiologist. Trauma protocols are helpful in evaluating and treating critically ill patients, establishing priorities, and guiding treatment (10). Arterial blood gas with blood lactate levels and/or base deficit analyses is a good indicator of the hemorrhagic state and tissue oxygenation and response to treatment (13, 14 and 15). Using an algorithm for the multiply injured patient with an unstable pelvic fracture (Fig. 37.4), Ertel et al. (13) documented survival in 15 of 20 patients (75%) with an average ISS of 41.2 ± 15.3. Fifteen patients had massive hemorrhage. Two patients required subdiaphragmatic clamping of the aorta to control exsanguination (16).

Imaging Studies

As part of the primary survey, a focused abdominal sonogram for trauma (FAST) or computed tomography (CT) scan (preferably with contrast) can be used to determine the presence of fluid in peritoneal cavity, retroperitoneal space, as well as assess arterial contrast extravasation (11,13,14). A chest x-ray is an important part of the trauma workup to rule out a pneumothorax, hemopneumothorax, tension pneumothorax, or flail chest as a cause of hypotension or shock. A single anteroposterior (AP) radiograph of the pelvis can be used to diagnose a pelvic fracture in approximately 90% of cases. X-ray signs of instability are (a) >5 mm of displacement of the sacroiliac (SI) joint in any plane (inlet and outlet views will improve accuracy if circumstances allow), (b) a posterior fracture gap, and (c) avulsions of the transverse process of fifth lumbar vertebra or the sacrospinous ligament.

Timing of Surgery

Damage control surgery to manage hemorrhage or severe contamination, with exploration and decompression of the head, chest, and abdomen, as well as débridement of open fractures have been shown to improve survival. Determination of the patient’s hemodynamic status and initial response to resuscitation place the patient into one of three categories that dictate subsequent treatment (Fig. 37.4). The first category includes patients who are “in extremis.” The second category includes patients who are hypotensive and in shock, and the third category includes patients whose vital signs stabilize with appropriate resuscitation and treatment.

Patients who present “in extremis” (i.e., without measurable vital signs) usually require a crash laparotomy, thoracotomy, and/or pelvic/abdominal packing with or without temporary aortic cross-clamping, in order to survive (Fig. 37.5). Temporary occlusion of the infrarenal aorta is possible via percutaneous or open balloon catheter techniques (17,18). Continued aggressive resuscitation therapy, a C-clamp (anterior or posterior), or an anterior pelvic external fixator should be applied urgently. If bleeding continues, pelvic or abdominal packing against a stabilized pelvis is more effective in controlling the bleeding.

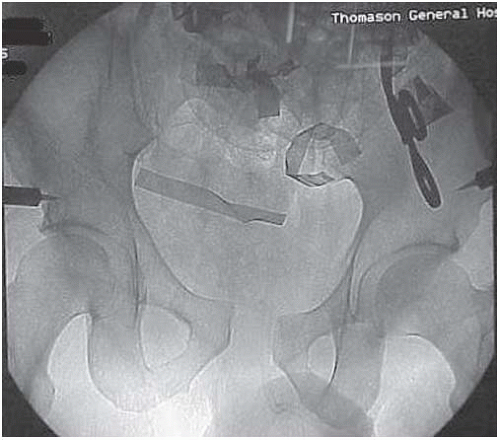

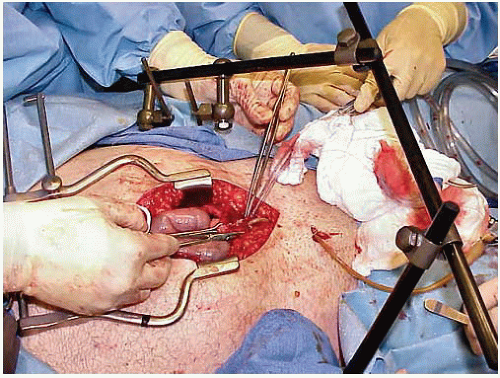

FIGURE 37.6 Laparotomy following application of an anterior external-fixation device. A C-clamp is covered by sheets. |

In another subset of patients whose shock persists despite adequate fluid replacement, blood transfusions, and vasopressors, consideration should be given to replacing the resuscitation pelvic sheet or binder with an external fixator or C-clamp. Numerous studies have shown that in patients with unstable pelvic injuries in which the ligaments and fascial planes that support the pelvic floor have been disrupted, self-tamponade rarely occurs (19). Huittinen and Slätis (20) estimated that up to 90% of bleeding following a pelvic fracture is the result of disruption of the lumbosacral venous plexus or the cancellous bone surfaces from the fracture site, while only 10% have an arterial origin. The most common technique for controlling the diffuse bleeding (venous or smaller arterial vessels) is by tamponade. In patients who require abdominal exploration, laparotomy may render the pelvis more unstable because the muscle forces pulling on the iliac wings are diminished (21). A correctly applied pelvic frame will improve pelvic stability without impeding the surgeon’s ability to perform a laparotomy (Fig. 37.6). If a patient with an unstable pelvic fracture requires a laparotomy for intraperitoneal injuries, exploration with retroperitoneal packing to control bleeding may be accomplished simultaneously. Disruption of the soft tissues in the pelvic floor allows direct access to both sides of sacrum and bladder for packing (22). Major vessel injury to the external iliac and femoral artery or vein also requires repair. In massive retroperitoneal bleeding caused by blunt trauma, Ertel et al. (13) recommended that the hematoma in the central zone be explored. This method allows assessment of the posterior pelvic reduction by direct manual palpation from inside the pelvis. Bone bleeding is better controlled when bony surfaces or the SI joints are directly opposed and compressed. If significant residual displacement exists, loosening and adjusting the external fixator may improve the fracture reduction and mechanical stability. If hemodynamic instability persists despite these measures including partial closure of the distal abdominal fascia for better support of the packing, the patient should undergo a CT angiogram of the abdomen and pelvis. The study is highly accurate in determining the presence or absence of ongoing pelvic hemorrhage (23). Patients with contrast extravasation may be candidates for angiographic embolization. Using a similar protocol, the Hannover Trauma Center was able to reduce mortality rate from 46% to 25% (14,16,20,22,24).

In most North American trauma centers, a sheet or pelvic binder is applied to unstable patients with a possible pelvic fracture during the initial evaluation and resuscitation. An ultrasound (FAST) of the abdomen and/or CT scan of the head, chest, abdomen, and pelvis is obtained. If there is no free fluid in these areas and the patient remains hemodynamically unstable, angiography with or without embolization is usually the next step. The problem with angiography is that it does not address venous bleeding, is time consuming, requires specialized personnel and equipment, and may cause gluteal muscle necrosis. In addition, only 10% of patients with pelvic fractures have a bleeding source amenable to embolization (10,12,25, 26 and 27). Recently, several investigators have popularized direct retroperitoneal packing below the pelvic brim after pelvic fracture stabilization using an external fixator or a C-clamp. In one study using this approach, only 4 of 24 patients who were hemodynamically unstable required subsequent angiography (10,28, 29 and 30).

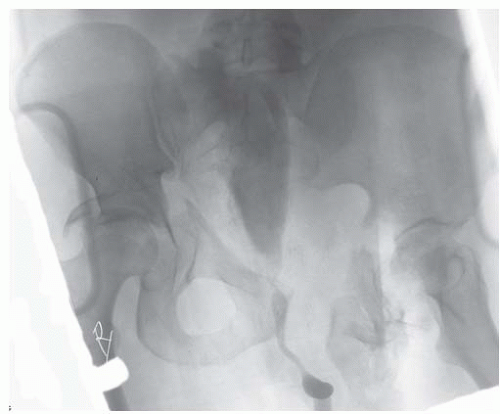

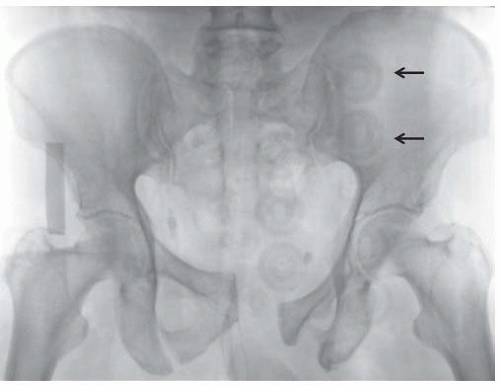

FIGURE 37.7 Unstable, complex pelvic, and bilateral acetabular fractures. A retrograde urethrogram is indicated to assess the integrity of the urethra and bladder before placement of Foley catheter. |

High-energy pelvic injuries with a major vessel injury such as the external or internal iliac or femoral artery or vein, with critical ischemia to the extremity, and a profound neurologic deficit cause such persistent hemodynamic instability that reconstruction attempts are usually futile. Fortunately, this is very rare, and survival often requires a life-saving hemipelvectomy (25,31).

Open fractures with wounds in and around the rectum or vagina require irrigation and débridement, and when large a diverting colostomy placed as far as possible from future incisions that will be used for definitive fracture surgery. An immediate distal-rectal washout should be considered, and broad spectrum intravenous antibiotics are mandatory (1, 2, 3, 4 and 5,9). In a closed pelvic injury with air present on CT in the pelvis, a rectal or colon injury must be ruled out by colonoscopy (32,33).

Virtually all male patients with unstable pelvic injuries, with or without blood around the urethral meatus, require a retrograde urethrogram before bladder catheterization (see Fig. 37.40). In our experience, a rectal exam cannot reliably predict the position of the prostate and possible urethral injury especially in the trauma patient. If the urethrogram shows extravasation of dye, a suprapubic catheter is inserted percutaneously or openly if a laparotomy is necessary. Patients with hematuria and an intact urethra require a contrast study to rule out a bladder rupture (Fig. 37.7). If no obvious source for the hematuria is identified, an abdominal CT or intravenous pyelography should be obtained to investigate the upper urogenital tract. In a polytrauma patient, CT scans without contrast can show kidney injuries, since contrast may be contraindicated in patients with renal damage or poor function. If an emergent invasive radiology procedure is necessary, contrast studies (urological and gastrointestinal) should be done after angiography (12,25,33).

PREOPERATIVE SURGICAL TACTIC

Pelvic Stabilization

Critically ill patients with unstable pelvic injuries require early pelvic stabilization to improve fracture stability, provide a tamponade effect, improve clotting, and reduce pain. In patients with multiple injuries, including other life-threatening conditions, the speed and safety of pelvic stabilization (Fig. 37.8 and Table 37.1) are more important than the initial accuracy of reduction or sophistication of frame constructs.

Noninvasive Methods

Hemodynamically unstable patients with a suspected pelvic injury should be placed into some type of pelvic circumferential compression device (PCCD). These devices lower transfusion rates and length of hospital stay (8,34,35). PCCDs can be as simple as a bed sheet wrapped and secured with towel clamps or a hand-tied knot placed around the pelvis and greater trochanter (Fig. 37.3). This method of stabilization is most effective when applied after a simple reduction maneuver using traction on the shortened extremity that clinically does not appear to be broken.

The knees are slightly flexed (muscles relaxed, supporting pillow), and the lower extremities are kept in internal rotation by taping the feet and legs together (Fig. 37.9, 32.10, 32.11, 32.12 and 37.13). As part of the secondary survey, the patient should be carefully “log rolled” onto their side for an examination of the spine and posterior pelvis including a rectal examination. If surgery is delayed, it is important to take the patient off the spine board onto a softer bed mattress to lessen the risk of pressure sores. Commercially available pelvic binders are easier to apply and readjust when needed (Figs. 37.9 and 37.12). However, these devices may limit access

to the abdomen and groin. If that is the case, the binder could be repositioned higher up to the iliac crests or distally to the greater trochanters. Vacuum splints and beanbag positioners, while bulky, can be helpful and allow better abdominal and inguinal access while providing pelvic immobilization (Fig. 37.13). PCCDs are temporary measures (not more than couple of hours) that are used until an unstable pelvic injury has been excluded by radiographs and CT scans, and hemodynamic stability has been restored or internal or external fixation performed (34).

to the abdomen and groin. If that is the case, the binder could be repositioned higher up to the iliac crests or distally to the greater trochanters. Vacuum splints and beanbag positioners, while bulky, can be helpful and allow better abdominal and inguinal access while providing pelvic immobilization (Fig. 37.13). PCCDs are temporary measures (not more than couple of hours) that are used until an unstable pelvic injury has been excluded by radiographs and CT scans, and hemodynamic stability has been restored or internal or external fixation performed (34).

TABLE 37.1 Methods of Pelvic Fracture Stabilization | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

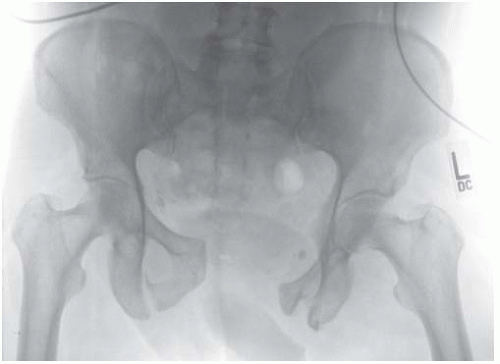

FIGURE 37.9 A trauma patient with the pelvis fracture stabilized with a pelvic binder. A right knee dislocation was reduced and protected with knee immobilizer. |

FIGURE 37.10 Pelvic AP x-ray from the patient from previous figure, indicating an unstable pelvic injury. |

FIGURE 37.11 Radiographs of the same patient after application of a pelvic binder and positioning the feet in internal rotation. |

FIGURE 37.12 The use of pelvic binder in a mechanically unstable, open, pelvic fracture. It is easy to apply and adjust as needed. Access to the abdomen and inguinal regions may be limited, and binder repositioning to the trochanteric regions may be necessary.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|