I. THE LIMPING CHILD. The limping child is frequently referred to a primary physician’s office or to an urgent/emergency care center. There is a long list of possible causes to be considered. Important components of the evaluation include a thorough history and a careful physical examination.1

A. History of present illness. Acuteness of onset of symptoms, pain, history of trauma or injury, constitutional symptoms such as fever, malaise, chills; ability to bear weight on affected leg and early morning stiffness.

B. Past medical history. This should include birth history and major motor milestone development history as well as any previous surgeries, injuries, or other major medical conditions.

C. Review of systems: Recent illnesses (upper respiratory tract illnesses [URTI; viral or streptococcal], gastrointestinal illness, etc.), rashes, joint swelling. Also, recent exposures such as camping or travelling to wooded areas as well as a history of tick-bites.

D. Family history. Family history of childhood lower extremity conditions such as developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH).

E. Physical examination. The child should be undressed to an appropriate state. Older children and teenagers should be provided with a gown or shorts. Toddlers and small children can be examined in their diaper or underwear. The physical examination should be tailored to each patient depending on the symptoms at presentation. The physical examination of a child with a recent or sudden onset of a painful limp or refusal to walk in the emergency department will be very different from an examination of a child with a chronic, painless limp in the outpatient clinic.

- Observation. An antalgic gait is characterized by a decreased stance period on the affected limb as well as a trunk shift over the affected limb during stance.

- Evaluation for limb length difference: Palpate the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS) with the patient standing. Then, with the patient supine, compare lengths of the lower extremities with the legs extended. Also, compare lengths of the femurs by flexing the hips and comparing the relative heights of the knees (Galeazzi sign).

- Physical examination should also include the back, sacroiliac joints, and abdomen as well as the entire extremity involved.

- Palpate the entire length of the limb.

- Evaluate the range of motion (ROM) of the hip, knee, and ankle joints. Particular attention should be paid to any erythema, warmth, joint effusion, or focal tenderness.

- A thorough neurologic examination should also be completed including motor strength, sensation, and reflexes.

F. The differential diagnosis for a limping child encompasses a broad range of conditions and depends on many factors including age, symptoms, severity, acuteness of onset, and clinical findings on physical examination.1,2

1. 0 to 5 years old

a. Septic arthritis

b. Osteomyelitis

c. Transient hip synovitis

d. DDH

e. Legg–Calvé–Perthes disease/osteochondroses-related conditions

f. Toddler’s fracture (nondisplaced tibia fracture)

g. “Nonaccidental injury” (child abuse)

h. Neurologic disorders (cerebral palsy, Duchenne muscular dystrophy)

i. Tumor (neuroblastoma, acute lymphocytic leukemia [ALL], benign tumors)

j. Discitis

k. Juvenile rheumatoid arthritis (JRA)

l. Congenital limb deficiency (femur, fibula, tibia)

2. 5 to 10 years old

a. Septic arthritis

b. Osteomyelitis

c. Transient synovitis

d. Osteochondroses conditions such as Perthes, Kohler, and Osgood–Schlatter disease

e. Limb length difference

f. Tumor (ALL, Ewing sarcoma, benign bone tumors)

g. Neurologic disorders

h. Discitis

i. JRA

j. Discoid meniscus

3. 10 to 15 years old

a. Osteomyelitis

b. Slipped capital femoral epiphysis (SCFE)

c. Osteochondroses conditions such as Perthes and Sever disease

d. Hip dysplasia

e. Patellofemoral pain syndrome

f. Tumor (osteosarcoma, Ewing sarcoma, benign bone tumors)

g. Osteochondritis disseccans (OCD)

h. Idiopathic chondrolysis

G. Radiographic evaluation. This should start with an anteroposterior (AP) and lateral plain radiograph (X-ray) of the area or body part suspected as a source of the patient’s pain. If the hip is the area of concern, an AP pelvis and “frogleg” lateral of the pelvis should be obtained. Referred pain describes pain attributed to one site or location by the patient when the source of the pain is at a different source (e.g., knee pain in a patient with an SCFE involving the hip joint). Referred pain is frequently seen with some childhood conditions.

H. Additional imaging studies

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). The MRI is very sensitive and specific for areas of abnormal signal in soft tissues as well as within the bone itself. It is able to identify areas of bone marrow edema, soft-tissue edema, or fluid collections such as abscesses or joint effusions. In younger children, MRI will require the help of the anesthesia team for sedation or a general anesthetic.

- Ultrasound (U/S). U/S is useful to look for hip joint effusions, subperiosteal abscesses, or soft-tissue abscesses. It may also help guide aspiration of hip joint or soft-tissue abscess.

- Three-phase bone scan. It may be useful when the source of pain is not easily localizable. It is sensitive but not specific.

Caution: If septic arthritis is suspected, a joint aspiration should be performed without wasting time waiting for the availability of other additional imaging studies.

I. Laboratory studies. For a patient with no history of trauma and/or who presents with fever, lethargy, or refusal to bear weight, the following lab studies be ordered:

a. Complete blood count (CBC) with differential

b. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR)

c. C-reactive protein (CRP).

d. If rheumatologic conditions or spondyloarthropathies are being considered, include rheumatoid factor, antinuclear antibody, antistreptolysin titer, and HLA B-27.

e. In endemic areas for Lyme disease and for patients with a large joint effusion, also include a Lyme titer.

II. THE CHILD WHO REFUSES TO WALK/BEAR WEIGHT

A. History

- Fever, lethargy, malaise, flu-like symptoms

- Pain: location, severity, frequency

- Trauma/injury

- Onset (sudden, gradual, etc.)

- Ability to bear weight on affected extremity

B. Physical evaluation

- Observe posture of patient/posture of limb

- Inspect for swelling, redness, deformity

- Palpate entire length of extremity, abdomen, spine for sites of pain, mass, warmth

- ROM active/passive, hip, knee, ankle joints

C. Radiograph. Obtain AP and lateral radiographs of the area identified as the location of the patient’s pain on physical examination.

D. Laboratory examination. EXTREMELY IMPORTANT:

- CBC with differential (may be normal)

- CRP (most sensitive)

- ESR

- Blood culture (particularly for patient with fever/sepsis)

E. Differential Diagnosis. When evaluating a patient with a fever, significant pain with attempted ROM and/or refusal to bear any weight or to walk, the primary physician should immediately notify the orthopaedic surgeon with whom they wish to consult. As soon as the laboratory studies and X-rays are available, the appropriate disposition of the child can be determined.

- Septic arthritis.This is a bacterial infection of a joint. It frequently affects the hip joint in toddlers and young children. It may also affect other joints of the lower extremity (knee, ankle, subtalar joint) or of the upper extremity (shoulder, elbow, wrist).

a. Febrile (>38.5 °C)

b. Elevated lab tests, especially CRP and ESR

c. Refuses to bear weight

d. Treatment: refer for evaluation and aspiration of joint (see VIII.B for additional information.)

2. Transient/toxic synovitis is a post-viral inflammatory condition most often affecting the hip in school-age children.

a. Afebrile

b. Lab results normal

c. Severity of joint pain may vary but child will often bear weight

d. Treatment: rest, NSAIDs, reevaluate (see VIII.C for additional information)

3. Osteomyelitis. This is a bacterial infection of the bone.

a. Febrile

b. Lab results elevated (especially CRP and ESR)

c. Pain with weight bearing

d. If unable to confirm diagnosis or localize, consider MRI

e. Treatment: Aspirate site for cultures and admit for IV antibiotics (see VIII.A for more information)

4. Fracture or other injury. If patient is too young to provide history, consider possible fracture or other significant injury.

a. History: Patient fell or found lying on floor if the injury was unwitnessed.

b. Physical examination: Inspect lower extremity for area of swelling, deformity or bruises. Palpate to locate area of tenderness.

c. Radiograph: Look for fracture or physeal separation. Children’s X-rays can be difficult to interpret because of the presence of growth plates (physes). If necessary, consider comparison X-rays of opposite limb.

d. Treatment: Splint injured limb and consult orthopaedic surgeon. Many pediatric fractures are difficult to see on initial radiographs. If fracture or injury is suspected, splint extremity until definitive diagnosis is made, which may require follow-up X-rays in 10 to 14 days.

5. SCFE (stable/chronic vs. unstable/acute) (see VII.C below)

a. Symptoms: Adolescent patient, often an overweight or obese male. Girls may often be thin. Patient with an unstable or acute SCFE has sudden onset of severe hip pain and inability to walk or bear weight on the affected limb. (For stable SCFE, the patient may complain of hip, thigh or knee pain but will be able to bear weight.)

b. Physical examination: In patients with an unstable SCFE, patient lies with hip flexed and externally rotated and has severe pain with any attempted ROM. In patients with a stable SCFE, patient has limited hip internal rotation and mild-to-moderate pain.

c. X-ray: Obtain AP pelvis X-ray and cross-table lateral X-ray of affected hip. Femoral epiphysis is displaced relative to femoral neck.

d. Treatment: Immediate referral to orthopaedic surgery for emergent surgical stabilization.

III. LOWER EXTREMITY ALIGNMENT CONDITIONS

A. Intoeing

- Definition. The feet turn in relative to the line of forward progression during walking. Intoeing is a frequent cause for parental concern. An important part of the evaluation should be listening to the concerns expressed by the parents and answering their questions.

B. Physical examination. The patient should be undressed adequately to visualize the lower extremities.

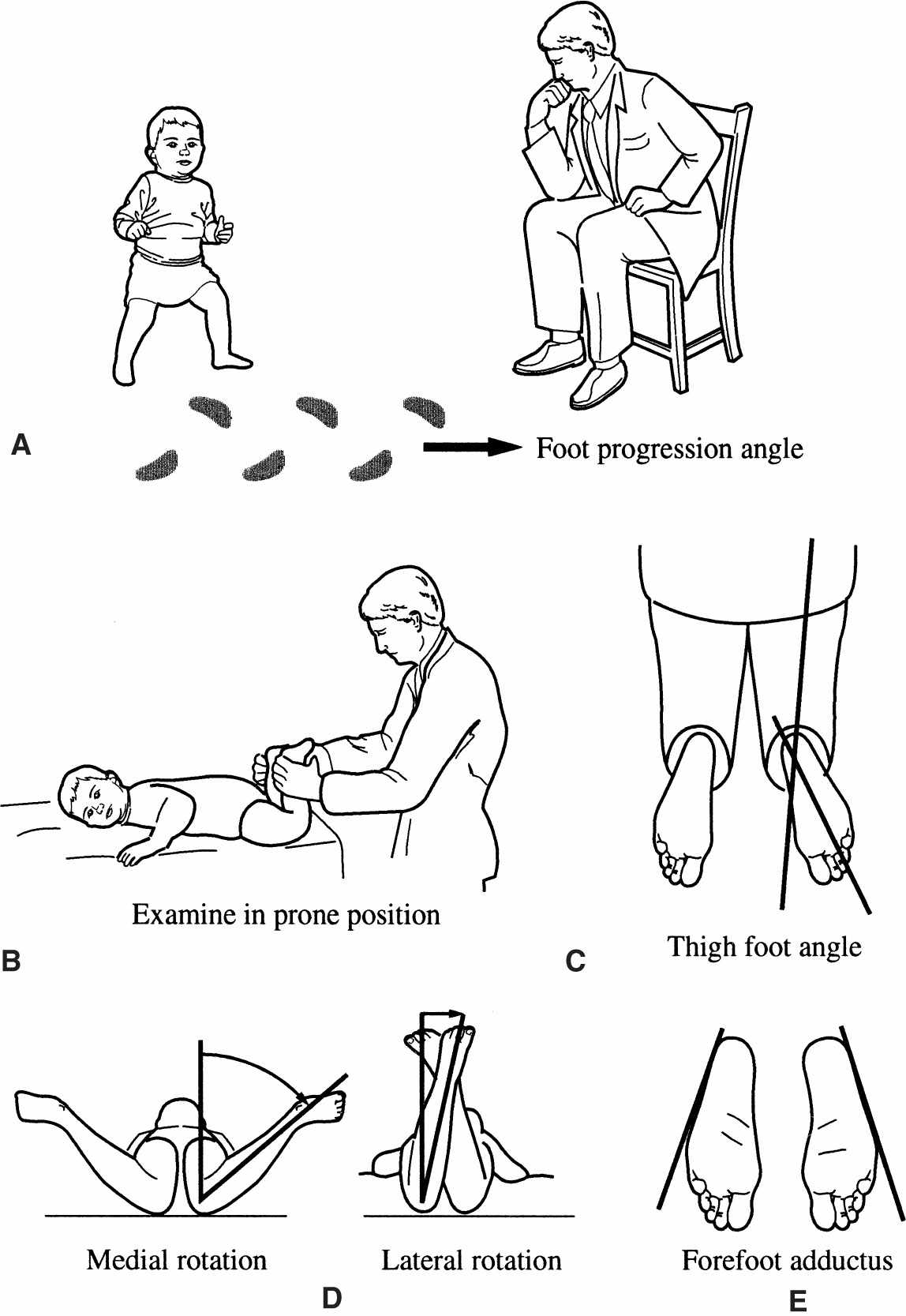

- Observation: Observe child walk in hallway. Note the position of feet relative to line of forward progression (Fig. 6-1).

Figure 6-1. Rotational profile. A: Observation of foot-progression angle. B: Examination of child in prone position to evaluate torsional deformity of the lower extremities. C: Thigh-foot angle. D: Hip internal (medial) rotation and external (lateral) rotation. E: Forefoot (metatarsus) adductus.

2. Examination: Evaluate rotational profile. Examiner should position patient prone (on their stomach) on examination table.

a. Hip internal (medial) and external (lateral) rotation (see Fig. 6-1D). With patient prone and knees flexed to 90°, rotate hip internally and externally until you can feel the position of rotation at which the greater trochanter of the femur is most prominent. Estimate the angle between the tibia and a vertical position in order to estimate femoral neck anteversion.

b. Estimate thigh-foot axis and bimalleolar axis in order to assess tibial torsion.

Thigh-foot axis (see Fig. 6-1C): Angle formed by line down the middle of the foot relative to line down the length of thigh.

Bimalleolar axis: Angle formed by a line passing through the center of lateral malleolus and medial malleolus relative to line perpendicular to the long axis of thigh.

c. Examine the plantar surface of the foot with the patient still in the prone position. Metatarsus adductus is defined as a curvature of the lateral border of the foot (see Fig. 6-1E).

C. Causes

- Increased femoral anteversion: Rotational twist in femur turns leg in while walking.

- Internal tibial torsion: Twist in tibia turns lower leg inward.

- Metatarsus adductus: Curvature of foot turns toes/forefoot inward.

D. Discussion. For most children, treatment of these conditions consists of education of the parents, reassurance, and observation. Intoeing is frequently seen in young patients and is a normal part of skeletal development for many children. The most frequent causes are increased femoral anteversion, internal tibial torsion, or metatarsus adductus. Normal femoral anteversion in the newborn is 40° to 45°. For most children, this gradually remodels with growth over time and will have improved by the age of 6 to 8. At skeletal maturity, normal femoral anteversion is approximately 10° to 15°. Increased femoral anteversion is femoral anteversion that persists longer than usual and is frequently associated with increased ligamentous laxity. Children with developmental delays or abnormal motor developmental conditions such as cerebral palsy will also frequently exhibit increased femoral anteversion. There are no forms of bracing, shoe-wear, or physical therapy that will help correct femoral anteversion. For most patients, it does not cause functional nor painful conditions later in life and should simply be observed.3

E. Internal tibial torsion is frequently seen as a cause of intoeing in infants and toddlers and also gradually corrects with time. It will correct more quickly than femoral anteversion and usually has improved by the age of 2 to 3.

F. Metatarsus adductus refers to a curvature of the lateral border of the foot. This is a frequent finding in newborn children and is often flexible. Simple massage and stretching can be performed by the parents for the first 6 months of life. If no improvement is seen, one may then consider a course of treatment with reverse-last shoes or bracing. If the foot does not appear flexible, a course of serial casting may be considered.

IV. LOWER EXTREMITY ALIGNMENT—“BOWED LEGS” OR “KNOCK KNEES”

A. Terminology

- Genu varum (bowed legs) genu-knee, varum/varus: The distal segment of the lower leg is aligned toward or close to the midline.

- Genu valgum (knock knees) genu-knee, valgum/valgus: The distal segment is aligned away from the midline.

B. Physical examination. The child should be undressed appropriately so that both lower extremities can be evaluated. The child should be assessed standing as well as supine and prone on the examination table. (Note that increased hip internal rotation associated with increased femoral anteversion can sometimes appear clinically as increased genu valgum. Therefore, the hip rotation profile should also be evaluated. See above.) The amount of angulation at the knee can be assessed in two ways.

- Femoral-tibial angle: Angle between thigh and lower leg.

- One can also measure and record the distance between bony landmarks.

a. Intercondylar distance (genu varum): The distance between the medial femoral condyles of the knees.

b. Intermalleolar distance (genu valgum): The distance between the medial malleoli of the ankles.

C. Radiographic evaluation. For either genu varum or genu valgum, standing AP hip to ankle radiographs of both lower extremities should be obtained. The mechanical axis as well as the anatomic axis of the lower extremity is measured. In young children with genu varum, the metaphyseal– diaphyseal angle is measured.4

D. Causes

- “Physiologic”: Part of the normal development. Most children who are referred for evaluation have a physiologic form of bowing. Children undergo an evolution of their lower extremity alignment during the first 6 years of life.

a. Birth to age 2: Genu varum.

b. Age 2 to 4: Genu valgum.

c. Age 4 to 6: Continued gradual correction into relatively “mature” alignment of mild genu valgum anatomically.5

For children who do not fit this pattern, are older (e.g., adolescent age), do not show resolution over time or appear to have asymmetric alignment of their lower extremities, other possible causes should be explored.

2. Tibia vara is an abnormal varus alignment of the knee because of altered growth of the medial portion of the proximal tibial physis. The infantile form (Blount disease) is associated with children between ages 1 and 4. Adolescent tibia vara is associated with partial closure of the growth plate in children of ages 6 to 13. Late-onset tibia vara is seen between ages 6 and 15 and is frequently associated with obesity.6

3. Other causes

a. Focal fibrocartilaginous dysplasia: A focal cartilaginous deformity of the distal femur or proximal tibia in young children leading to bowing.

b. Coxa vara: A congenital varus deformity of the proximal femur.

c. One of the various forms of skeletal dysplasias. To help evaluate this, obtain additional radiographs of the hands, shoulders, and spine.

d. One of the forms of Rickets (e.g., familial hypophosphatemic rickets). To evaluate this further, consider obtaining laboratory studies including vitamin D; parathyroid hormone; alkaline phosphatase; calcium, magnesium, and phosphorus levels. Also consider obtaining an endocrinology consultation.

E. Treatment

- For physiologic conditions, treatment usually consists of observation. Inform the patient’s parents of the expected course and communicate the findings and recommendations to the patient’s primary physician. Continued observation can be performed during routine well-child checks. If the child’s alignment varies from what is expected, the child can return for reevaluation.

- Children with conditions that do not fit the typical “physiologic” pattern should be referred for further evaluation. Further treatment consists of establishing the underlying cause as well as developing an appropriate treatment plan. After the diagnosis has been determined, treatment may consist of the following:

a. Observation

b. Hemiepiphyseal growth modulation (guided growth)

c. Hemiepiphysiodesis

d. Tibial and/or femoral osteotomy

These should be performed by physicians who are experienced in planning and performing the appropriate procedures and who are able to provide appropriate follow-up care.

V. COMMON CHILDHOOD FOOT CONDITIONS

A. Clubfoot (talipes equinovarus)

- Description. A congenital deformity of the foot comprised of ankle equinus, hindfoot varus, midfoot cavus, and forefoot adduction and supination. The foot “turns in” and “curves under” compared with the normal appearance.

- Incidence. Approximately 1 in 1,000 live births, unilateral in 60% of patients, and the ratio of boys to girls is 2:1. There may be a positive family history.

- Etiology. Multiple theories exist with the most likely cause being multifactorial. Theories include arrested fetal development, abnormal intrauterine forces, abnormal muscle fiber type, abnormal neuromuscular function, and germ plasm defects.

- Prenatal considerations. The diagnosis of clubfeet for the unborn child is often made on a prenatal U/S. If consulted by an expectant mother or primary physician, reassurances should be made that the diagnosis of clubfoot/clubfeet is a very treatable condition. Other prenatal factors associated with clubfeet include breech position, large birth weight, and oligohydramnios.

- Associated conditions include arthrogryposis, myelodysplasia, congenital limb anomalies, and various syndromes.

- Physical examination. A careful evaluation should include the child’s upper extremities, back, spine, and hips in order to look for other associated conditions. Examination of the feet should include evaluation of the ankle dorsiflexion, the hindfoot position, curvature of the lateral border of the foot, and the forefoot position as well as an assessment of the overall flexibility of the foot. Deep posterior and medial creases are frequently present.

- Radiographic evaluation. Radiographs in the newborn period are not useful because the tarsal bones are not well ossified. As treatment for patients with clubfeet has shifted to largely nonoperative methods, the role or need for radiographs has decreased. When an X-ray is deemed necessary, an AP and a lateral radiograph of the foot in maximum dorsiflexion are ordered for infants and children younger than 1 year. In children of walking age, a standing AP and lateral radiograph of the foot are requested.

- Treatment. The goals of treatment are to achieve a plantigrade, flexible, painless foot. The later half of the 20th century saw the emergence and rise in popularity of the surgical treatment of clubfoot. However, long-term results of surgical treatment have revealed high rates of foot pain and stiffness.7 Nonoperative treatment using the casting method developed by Ponseti has now gained wide acceptance and is currently the method of choice for most centers around the world.8 A nonoperative method of taping and physiotherapy popularized in France has also been embraced in some centers.9 Surgical treatment is reserved for those patients whose feet do not respond to nonoperative treatment.

B. Congenital vertical talus (CVT)

- Definition: A congenital condition in which the foot has a rigid flatfoot appearance due to an irreducible dorsal dislocation of the navicular on the talus. Often referred to as a “rocker bottom” foot deformity.

- Incidence: Much less common than clubfoot; the incidence is approximately 1 per 10,000 live births.

- Associated conditions: Approximately 50% of cases of CVT are associated with underlying disorders such as arthrogryposis, myelomeningocele, tethered spinal cord, or chromosomal abnormalities.

- Physical examination: When evaluating the child’s feet, assess the flexibility of the ankle and hindfoot as well as the posture of the midfoot and forefoot. Also remember to examine the child for other associated conditions involving their upper extremities, the spine, the hips, and their neurologic function.

- Radiographic evaluation: In contrast to children with clubfeet, for young children with suspected CVT, radiographs may be helpful in confirming the diagnosis. An AP and lateral X-ray of the foot in maximum plantarflexion should be obtained. For children with a CVT, the talus will remain plantarflexed on the lateral X-ray and will not align with the forefoot. The term oblique talus is sometimes used to describe the child with a flat or rounded appearing foot at birth but for whom the talus does line up with the first metatarsal or forefoot on the lateral plantarflexion X-ray. In patients with a calcaneovalgus foot at birth, the foot appears very dorsiflexed at birth and may have a rounded appearance but it has excellent flexibility of the ankle as well as of the midfoot and hindfoot.

- Treatment: For patients with a confirmed CVT, treatment has consisted of surgical correction either with a single-incision technique or with a two-incision technique. However, for patients with idiopathic CVT, there is now emerging a treatment method based on initial nonoperative, casting techniques with limited surgical treatment. This is showing promising results with the early studies available.10,11

C. Flat feet (pes planus)

- Definition. Feet in which the medial longitudinal arch is absent resulting in hindfoot valgus and forefoot supination.

- Presentation

a. Parental concerns regarding the appearance and shape of the foot

b. Pain

c. Difficulties with shoe wear

3. Patient history. It is important to note when the foot position was first noticed, whether the foot condition causes problems with function or pain, and any family history of ligamentous laxity/hypermobility or flatfeet.

4. Physical examination

a. Observe the foot while the patient stands and walks. Note presence or absence of medial longitudinal arch.

b. Inspect the foot for calluses and pressure areas over bony prominences.

c. When the patient is standing, have him or her stand on tiptoe to assess mobility of the hindfoot. If the hindfoot moves from valgus when plantigrade to varus with standing on tiptoe and the foot forms an arch when on tiptoe, the foot is “flexible.” If it does not correct, it is considered “rigid.”

d. Assess the length of the Achilles tendon by examining the range of ankle dorsiflexion.

5. Radiographic examination. For young children with a painless, flexible flat foot, no radiographs are indicated. If the flat foot is painful or rigid, standing AP, lateral, and oblique radiographs of the foot should be obtained.

6. Flexible flat feet. The flexible flat foot is a relatively common condition, although the true incidence is unknown. Most young children start with a flexible flat foot before developing a medial longitudinal arch during the first decade of life. Most children are symptom free, and no treatment is warranted. For the older child or adolescent with a flexible flat foot who experiences aching or discomfort associated with particular activities, one may wish to use an orthotic to support the arch. If the foot is flexible but there is a contracture of the Achilles tendon, one should prescribe a course of physical therapy for a heelcord stretching program. If the patient with an Achilles tendon contracture remains symptomatic despite physical therapy, one may consider injection of Botox into the calf muscle, possibly in conjunction with a stretching cast. For patients who fail conservative therapy, some authors support surgical correction of the hindfoot valgus deformity in conjunction with lengthening the tight gastrocnemius.12 This is rarely necessary in the growing child with a flexible flat foot deformity.

7. Rigid flat feet. The most common cause for a rigid flat foot is a tarsal coalition. This is an incomplete separation of the tarsal bones during fetal development. The two most common types are the calcaneonavicular and the talocalcaneal coalition. The calcaneonavicular coalition may be best seen on the oblique foot radiograph. The talocalcaneal coalition is difficult to see with plain radiographs. If further radiographic imaging is required when plain radiographs are nondiagnostic, a computed tomography (CT) scan of both feet is the study of choice.

8. If tarsal coalition has been excluded as the cause for the rigid flat foot, other possible causes include the following:

a. CVT

b. JRA or other sources of inflammation/irritability involving the subtalar joint

c. Neuromuscular conditions

9. Treatment of the rigid flat foot. The goal of treatment is to achieve a pain-free, asymptomatic foot. Approximately 75% of patients with tarsal coalitions are asymptomatic. Frequently, the onset of pain coincides with the transition during childhood of the coalition from a fibrous or cartilaginous (i.e., flexible) structure to a bony bar. For the calcaneonavicular bar, this occurs around ages 8 to 12; for the talocalcaneal bar, this usually occurs between ages 12 and 16. Nonoperative treatment consists of applying a short-leg walking cast for 6 weeks followed by use of a molded orthotic. This results in a resolution of the patient’s symptoms in a large number of patients. For patients who do not respond to casting treatment or for whom the symptoms recur, surgery is indicated. For patients with a calcaneonavicular coalition, operative treatment usually consists of excision of the coalition along with interposition of fat, muscle, or tendon to prevent recurrence.13 For patients with a talocalcaneal coalition, good results have been obtained with resection when the coalition comprises less than one-third of the total subtalar joint surface.14 For patients with severe degenerative arthrosis of the subtalar joint or persistent pain following previous resection, a triple arthrodesis may be considered.

D. Bunions (hallux valgus)

- Definition. An abnormal bony prominence of the medial eminence of the first metatarsal associated with a hallux valgus deformity of the great toe. It is frequently associated with a medial deviation of the first metatarsal (metatarsus primus varus).

- Patient history. These patients are most often adolescent or teenage girls with complaints of pain over the medial eminence, difficulty with shoe wear, or concerns regarding appearance. There may be a positive family history.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree