Chapter 4 Patient Evaluation, Cartilage Defect, and Evidence

Putting It All Together

The decision to proceed with joint preservation

The History

“I have been referred to see you by Dr. X for a specific knee reconstructive procedure.”

“I have no pain, but I was sent here because I have a cartilage defect.”

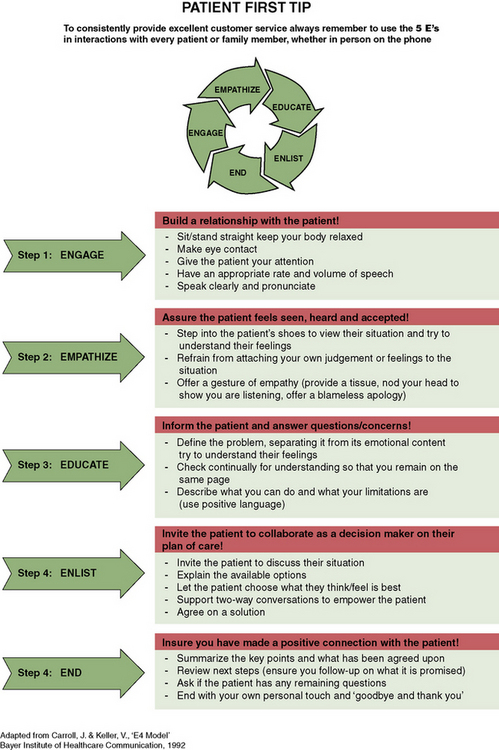

Alternatively, the patient may be self-referred based on his or her own ambitions. This is becoming more commonplace in the modern age of the Internet because patients are often well informed and wish to take matters into their own hands (“empowerment of the patient”). Figure 4–1 illustrates this concept. A useful tool for developing a healthy relationship with the patient is the five Es (Figure 4–2).

Patient Characteristics

The surgeon’s recommendation of treatment options may well depend on patient characteristics. A patient who has a high sense of vitality and an optimistic outlook with strong social supports has demonstrated a good clinical outcome with almost any surgical procedure. We reviewed our clinical outcome data using the Medical Outcomes Study 36-Item Health Survey (SF-36)1 and noted that vitality and social supports played strong into a positive clinical outcome with regard to physical pain relief and well-being (presented at the International Cartilage Repair Society 2002). I have also found that patients who are athletic at baseline and had a relatively acute injury less than 1 year do better clinically after surgery.2–4 It is suspected that as the athlete becomes deconditioned, the injury becomes chronic, with thickened subchondral bone and expanding margins such that both the patient and the lesion require more extensive rehabilitation. Obesity is another factor that surgeons encounter. It is approaching epidemic proportions in the United States, with approximately 30% of the population being considered obese. The osteotomy literature had demonstrated that body weight greater than 1.32 times normal adversely affects the outcome and survivorship of osteotomy surgery.5 Obesity has also been shown to correlate with an increased incidence of osteoarthritis, which presumably corresponds to enlargement of an existing cartilage defect, or factors adversely toward a cartilage repair procedure because of the force across the regenerative tissue. Counseling the patient regarding weight loss prior to a biologic repair procedure may actually prevent the need for the procedure based on symptom relief with weight loss. For the morbidly obese with body mass index (BMI) greater than 40, surgical gastric bypass surgery may be necessary. Some insurance carriers in the United States will not allow cartilage repair for patients with BMI greater than 30; for other carriers the cutoff is BMI of 35. Further research on the correlation between weight and progression of cartilage damage is necessary.

Injured knee

As discussed in Chapter 1 on the characteristics that predispose to progression of cartilage injuries to osteoarthritis, a thorough evaluation that assesses the background factors of cartilage loss is critical to the potential success of a biologic preserving procedure. Radiographic studies to delineate long axial alignment of the limb relative to the knee joint and weight-bearing x-ray films in extension and flexion to assess joint space narrowing or complete obliteration (a good screening tool to rule out the possibility of cartilage repair and recommend osteotomy or arthroplasty in isolation) must be performed.

If a cartilage injury is suspected, a high-resolution MRI scan with intraarticular dye enhancement (either indirect intravenous gadolinium arthrogram6 or direct intraarticular arthrogram) will maximize the information obtained prior to making any recommendations for surgery. In this way, leg alignment and normal cartilage space are assessed, cartilage defect(s) is delineated, underlying bone marrow edema or cysts are identified, volume and status of the menisci are determined, and preservation of the anterior and posterior cruciate ligaments is noted. Contracture of the Hoffa fat pad as well as intra-articular adhesions, loose bodies, synovitis, and effusion may be identified.

Critical Cartilage Defect Size

Cartilage defects may be present and minimally symptomatic if the defect is small or the activity level is insufficient to cause progression of disease. Previous studies have reported that 2-cm2 lesions coexist without degenerative changes in the knee up to 4 years after onset of symptoms.7,8 More recent studies have shown no difference in clinical outcomes in anterior cruciate ligament–injured and stabilized knees with 2.1-cm2 chondral defects at 15 years compared with controls in 36 knees.9 This finding supports the idea that progression of lesions smaller than 2 cm2 is unlikely and that 2 cm2 may represent a critical defect size. Based on these studies, early algorithms delineated 2 cm2 as a small defect.10–12

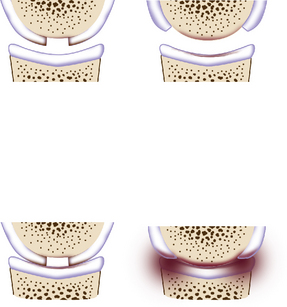

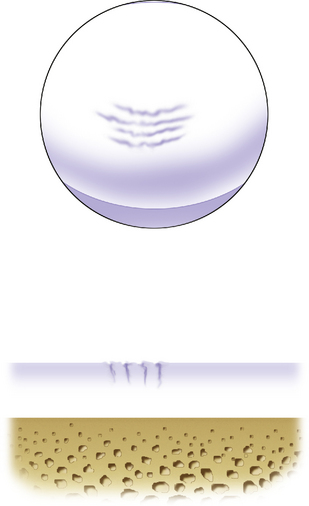

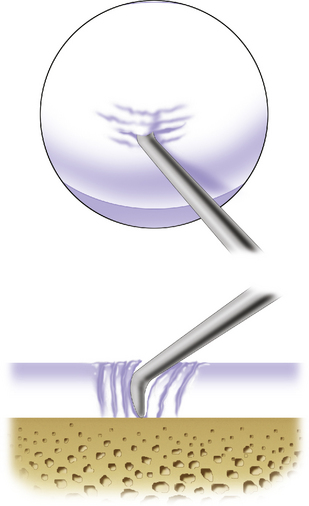

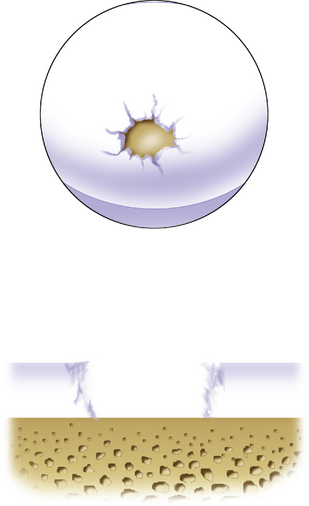

A critical size defect is considered a defect that shoulders the subchondral bone well from stimulus, thus lessening the symptoms from subchondral bone nerve stimulation and the abrasive effects of subchondral bone on the opposing articular cartilage and therefore the development of bipolar changes. A larger defect that is poorly shouldered will damage the opposing articular surface, resulting in progressive joint space cartilage loss, will remain symptomatic, and will enlarge quickly because of the excessive force on the edges of the defect. Figure 4–3 demonstrates this principle, which we described previously.12

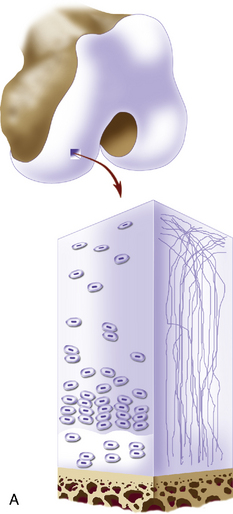

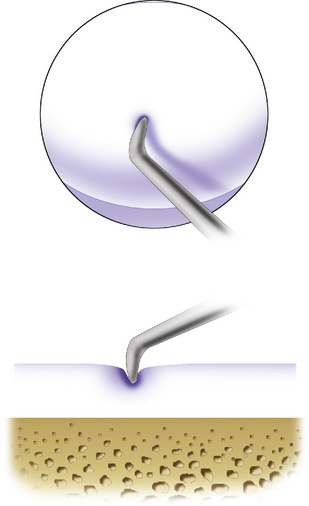

A relatively small defect that is symptomatic may be either treated by arthroscopic debridement of the unstable margins and then left alone, or stabilized with a repair tissue of fibrocartilaginous or hyaline cartilage. However, a larger poorly shouldered chondral defect will require a repair tissue with the same or nearly the same viscoelastic and mechanical properties as normal hyaline cartilage (Figure 4–4). Procedures that may produce hyaline-like cartilage for this situation are discussed in the remainder of this chapter (Figure 4–5).

Prevalence of Articular Cartilage Injury

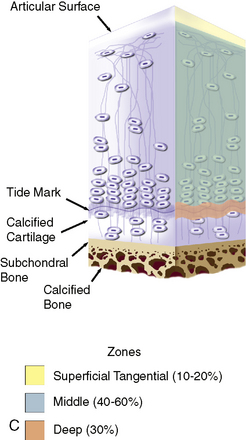

The spectrum of disease entities that cause damage to the articular cartilage ranges from single, focal chondral defects to more advanced degenerative disease. Focal chondral defects result from various etiologies. An approximately even number of patients have reported a traumatic versus an insidious onset of symptoms. Athletic activities are the most common inciting event associated with the diagnosis of chondral lesions.13 Traumatic events and developmental etiologies such as osteochondritis dissecans predominate in younger age groups. Several large studies have found high-grade chondral lesions (Outerbridge grades III and IV; Figure 4–6) in 5% to 11% of younger patients (<40 years) and in up to 60% of older patients.13–15 The most common locations for these defects are the medial femoral condyle (up to 32%) and the patella.14,15 Most are detected incidentally during meniscectomy or anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction.13,16 Many of these defects are incidental in nature and asymptomatic.

The Asymptomatic Defect

The patient may have a known cartilage defect that is relatively asymptomatic. The question then becomes, “Will the lesion progress over time?” I have counseled patients in this situation to modify their activities to avoid impact and torsional sports and to cross-train with activities such as cycling, swimming, elliptical trainer, and upper-body weight training. These patients are followed-up with annual high-resolution MRI scans to determine whether the defect size is enlarging (Figure 4–7

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree