Chapter 6 Patient education and self management

KEY POINTS

Patient education should be planned and have a sound theoretical base, applying health psychology and educational theory to practice.

Patient education should be planned and have a sound theoretical base, applying health psychology and educational theory to practice. Patient education should strengthen self-efficacy and teach self-management skills effectively, allowing adequate practise with feedback.

Patient education should strengthen self-efficacy and teach self-management skills effectively, allowing adequate practise with feedback.DEFINING PATIENT EDUCATION

Patient education is any combination of planned and organized learning experiences designed to facilitate voluntary adoption of behaviour and/or beliefs conducive to health (Burckhardt et al 1994).

This definition points out the main issues of patient education: interventions ought to be planned just as in any other therapeutic intervention. This requires assessment of patients’ educational needs, definition of educational goals, clear plans and procedures for achieving these and (re)evaluation. Targets may be attitudes, beliefs, motivation and behaviour. A basic knowledge and understanding of the disease and possible interventions is helpful, but knowledge does not necessarily lead to changes in attitudes and behaviour. A systematic approach should be used as knowledge, attitudes, values, emotions and behaviours influence each other. The patient’s decision for behavioural change is always voluntary – the health professionals’ task is to provide effective interventions and optimal learning situations. A summary of patient education approaches is provided in Table 6.1.

Table 6.1 Summary of patient education approaches

| APPROACH | EDUCATIONAL METHODS | EXAMPLE |

|---|---|---|

| Educational | Information | Using a teaching approach, e.g. short lectures, explanations, written information. |

| Counselling | Counselling | Communication approach, specifically adapted to and reinforcing individual’s motivation |

| Psycho-educational | Cognitive behavioral interventions Motivational interviewing | Assessing and enabling changes in beliefs and attitudes; problem solving; skills training; goal-setting and contracting; home programmes. |

SELF-MANAGEMENT

Self-management is the ‘individual’s ability to manage the symptoms, treatment, physical and psychosocial consequences and life style changes inherent in living with a chronic condition’ (Barlow et al 2002, Newman et al 2004). This implies several important points:

EMPOWERMENT

Empowerment is a relatively new term in the context of care but is an important aim in relation to self-management. It’s the precondition for and consequence of self-management ability. Empowered patients are able to develop and strengthen their own (health) competencies, such as the appropriate knowledge, attitudes and skills needed to cope with the disease in their own life context (Virtanen et al 2007).

DEVELOPING PATIENT EDUCATION INTERVENTIONS: A 7-STEP APPROACH

Taal et al (1996) suggested a 7-step approach for the development, conduct and evaluation of patient education (Box 6.1). This structure is applied in this chapter.

BOX 6.1 7-step approach to development of patient education

(after Taal et al 1997)

STEP 1: ANALYSE THE PROBLEMS

Important factors influencing health behaviour and coping are:

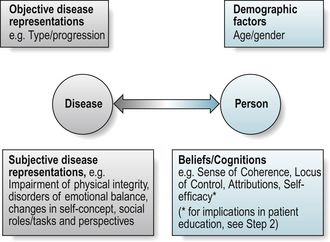

There is evidence that individual beliefs and attitudes are better predictors of patients’ abilities to cope with the illness than disease severity, age or gender (Buchi et al 1998) (Fig. 6.1).

Beliefs or cognitions: sense of coherence, health locus of control, self-efficacy

Sense of coherence (SOC) is considered as an adaptive dispositional orientation (i.e. within the personality) that enables coping with adverse experience (Antonovsky 1979, 1990, Eriksson & Lindstrom 2006). SOC integrates the meaningfulness, comprehensibility and manageability of a situation or disease. The more a person is able to understand and integrate (comprehensibility), to handle (manageability) and to make sense (meaningfulness) of an experience or disease, the greater the individual’s potential to successfully cope with the situation or the disease. As it is a personality trait it is more likely to be a predictor of behaviour than a factor to influence in interventions. High SOC is associated with perceived good health and predictive of positive health outcomes (Eriksson & Lindstrom 2005).

Health locus of control (HLC)(Rotter 1954) differentiates between whether people attribute an outcome to their own abilities or actions and, as such, is under their personal (internal) control (e.g. I did not exercise enough today because I was not in the mood, or did not put in enough effort) or whether an outcome is independent of one’s actions (external control), attributing it to fate or chance (e.g. bad weather, no time, no social support). Findings related to HLC predicting health behaviour are weak and inconsistent (Wallston 1992) (see Ch. 5, Section 4).

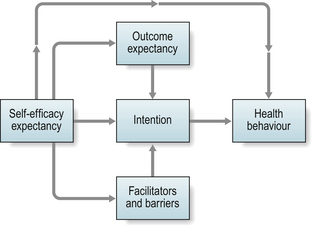

Self-efficacy theory is considered as one of the most powerful determinants of behaviour (Bandura 1977). The confidence a person has to successfully execute a specific behaviour or task in the future, i.e. (self)-efficacy expectation, and the person’s belief that the desired behaviour has a positive effect, i.e. outcome expectation, determine the initiation of the process to perform a behaviour, to expend effort and to continue to do so when difficulties are arising (Bandura 1990). (See Ch. 5, Section 4).

Self-efficacy refers to perceived ability in specific domains of activities. It is a specific state, although a variety and range of positive mastery experiences may lead to a general sense of self-efficacy (Bandura 1977). A patient with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) might very well have high self-efficacy to follow a drug prescription correctly but low self-efficacy for using joint protection methods correctly.

Patients with chronic diseases who demonstrate high self-efficacy have a better prediction for rehabilitation outcome (Hammond et al 1999). In people with RA, higher self-efficacy has been shown to be associated with better ability to cope with their disease, as well as with better current (Taal et al 1996) and future (2 and 5 year) health status (Brekke et al 2001, 2003).

Motivation and goal setting

Adopting health behaviours is ‘unfortunately’ not just a logical, rational decision-making process solely dependent on information. Rather it depends on complex interactions, including attitudes to illness, expectations of health, previous experiences of the illness and social pressure (Price 2008).

Motivation for behavioural change is determined by cognitions, emotions and intentions and is central for applying what has been learned. The distinction between approach (success-related) and avoidance (failure-related) motivation is fundamental in explaining human behaviour (Elliot et al 2001). Important factors for effective goals are that they should be:

Compliance, adherence and concordance

In the past, there was much focus on patient’s compliance with treatment. The term compliance denotes following a prescribed regimen, indicating a more passive patient role. This is an inappropriate term in therapy as we work collaboratively with clients. Adherence suggests a more equitable role in which the patient participates in goal-setting and treatment with shared responsibility for outcome (Agras 1989) and probably reflects well the tenacity patients with chronic disease need to maintain behavioral adjustments over their life (-time) (Haynes et al 2002, Price 2008). In relation to medication-taking the term concordance is now commonplace. It refers to the interactional decision-making process in agreeing a management plan between patient and health professional. Partnership may optimise therapy and health gains and discordance is resolved through compromise or agreeing to disagree (Treharne et al 2006). “Concordance” is likely to become a more common term in therapy practice in future.

Adherence to treatment

Non-adherence is considered as one of the main barriers to the effectiveness of treatment interventions (Carr 2001). The following factors are important determinants of adherence:

Social support

Family and friends form a social network that may be a source for social support. However, this may be perceived as positive or problematic, contributing to decreased or increased depression respectively in people with RA. Size and perceived availability of social network contribute to reducing negative affective reactions of patients with RA (Fitzpatrick et al 1988). Support is problematic when it is not needed or desired or when it does not meet the recipient’s needs. Both, positive and problematic support were demonstrated to be associated with coping and depression with arthritis (Revenson et al 1991) and lack of sympathy and understanding from the social network contributes to fatigue (Riemsma et al 1998). Positive and negative social support has the same effects on men and women, but effective social support strategies differ between men and women (Kraaimaat et al 1995). For women, it is their perceived degree of emotional support, whilst for men it is the number of friends that significantly contributes to support.

There are inconsistent findings as to whether family members should participate in self-management education programmes. There are studies reporting no effects (van Lankveld et al 2004) or even negative effects on self-efficacy and fatigue (Riemsma et al 2003a,b). Positive effects have also been identified, such as high levels of satisfaction with social support and positive quality of life outcomes (Minnock et al 2003), quality of marital status and pain severity (Waltz et al 1998).

STEP 2: MAKE USE OF A THEORETICAL MODEL

Several models and theories are commonly used in patient education.

The Health Belief Model

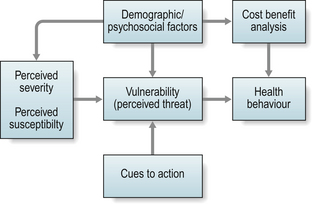

The Health Belief Model (HBM) (Becker et al 1977) (see Ch. 5) is one of the oldest models but still provides an important framework for designing theory-based interventions, though newer models and their components seem to better explain the complexity of behaviour (and behaviour changes) (Fig. 6.2).

The implications for patient education are:

Low perceived susceptibility may reduce motivation. There is some evidence that increasing worries created by information (e.g. mass media campaigns, information booklets) can help to change (self-reported) health behaviour (Sogaard & Fonnebo 1992).

The Theory of Reasoned Action and Theory of Planned Behaviour

The Theory of Reasoned Action (Fishbein & Ajzen 1975) and the Theory of Planned Behaviour (Ajzen 1985) (see Ch. 5) also consider intention and perceived control as other important determinants for health behaviour. Intention towards a behaviour is shaped by the person’s attitudes and subjective norm (expectancies of social environment) which act as pros and cons towards a behaviour. Perceived control emerged from work on locus of control and perceived self-efficacy and it was assumed that intention and perceived control interact.

The implications for patient education are:

Social Cognitive Theory

Self-efficacy (Bandura 1977, 1990) is a central concept in social cognitive theory and is acquired by direct experience, vicarious experience (role modelling), verbal persuasion and reinterpretation of physiological signals. Action-oriented interventions in occupational and physiotherapy provide unique possibilities to acquire self-efficacy. Direct experience is the most powerful strategy. Success leads to success (see Chs. 5 & 6, Steps 1 & 5) (Fig. 6.3).

The implications for patient education are:

The Transtheoretical Model

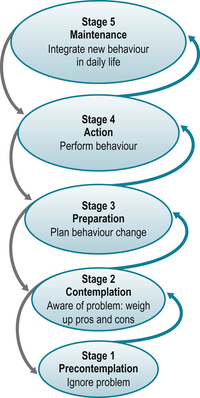

The development of the Transtheoretical Model (TTM) (Prochaska et al 1992) was an important step to better understand behavioural change, demonstrating that individuals cycle through a series of five stages of readiness to change when modifying health behaviours.

In the pre-contemplation and contemplation stages there is no or little problem awareness and thus no intention to change in the future (i.e. the next 3–6 months). In the preparation stage taking action is planned for the near future (i.e. within a month). In the action stage activities are performed to modify behaviour, experiences or the environment and in the maintenance stage the new behaviour is consolidated and integrated into daily life (i.e. it is performed regularly over at least 6 months). Behaviour change takes time and regression, i.e. relapse into previous behaviours, is the rule rather than the exception, visualised by the spiral pattern of the TTM (Fig. 6.4).

The implications for patient education are:

Adult Learning-the learning process

Health professionals have the responsibility to fully explore the patient’s situation and tailor interventions based on personal needs, anticipate patients’ difficulties in following recommendations and communicate in a way that is effective (Stone 1979). Learning, i.e. gathering knowledge and skills, is not automatic and has to be enhanced by teaching and methodological choices. Favourable learning situations involve several learning processes. Learning processes do not occur in isolation but in combination (Berlinger et al 2006).

Learning as a self-directed process

Self-directedness (Fig. 6.5) is:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree