Chapter 10 Patellofemoral Malalignment, Tibial Tubercle Osteotomy, and Trochleoplasty

Introduction

The prevalence of patellofemoral cartilage defects is controversial because the percentage of lesions that become sufficiently symptomatic to prompt evaluation is unknown. Several studies have reported the presence of high-grade focal chondral defects in 11% to 20% of knee arthroscopies. Among these defects, 11% to 23% were located in the patella and 6% to 15% in the trochlea.1–3 A group investigating asymptomatic National Basketball Association players with knee magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) found articular cartilage lesions in 47%, with patellar lesions in 35% and trochlear lesions in 25% of players; however, only approximately half of these defects were characterized as high-grade lesions.4 These reports emphasize the importance of a thorough history and physical evaluation of the entire kinetic chain from pelvis to foot, a gait analysis, and assessment of all knee structures (tendons, ligaments, and soft tissues) before attributing a patient’s symptoms solely to the presence of a chondral defect.

History

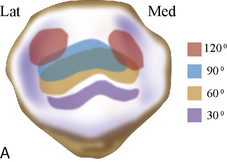

Patellofemoral articular defects frequently present as anterior knee pain. Patients often report the pain is located retropatellar, peripatellar, occasionally radiating “down the shin bone,” or, in the case of trochlear defects, posteriorly in the popliteal area. Secondary pain may derive from synovial or capsular irritation from joint distension secondary to an effusion or exposed subchondral bone overload from a chondral defect. Thus, in light of the secondary nature of pain, other factors may also contribute so that assigning a percentage of pain to the cartilage pathology can be difficult. Large defects can cause clicking or popping, giving way, and activity-related swelling. Distension of the joint often causes an aching sensation, with loss of motion and function but not necessarily complaints of pain. Standard patellofemoral symptoms are often reported, such as increased pain with prolonged flexed knee position and stair climbing, as maximal patellofemoral forces occur in the flexed knee position when patellar engagement in the trochlea is greater than 30 degrees (Figure 10–1). Patients are approximately evenly split in reporting a traumatic versus a more gradual onset of symptoms. Participation in sports was the most common inciting event associated with the diagnosis of chondral lesions. Patellar dislocation is associated with damage to the articular surface, with chondral defects of the patella seen in up to 95% of patients (Figure 10–2).5 It is my opinion that patellar dislocations usually occur due to baseline mechanical abnormalities with increased Q angles and/or dysplasia of the trochlea. Despite the history of trauma, usually a minor twist occurs during participation in sports. Patients often report extended courses of physical therapy, bracing and taping, or prior knee surgery.

Physical examination

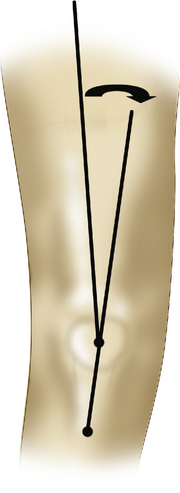

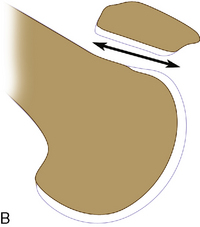

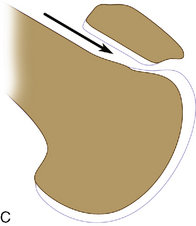

Gait abnormalities, such as intoeing and hip abductor weakness, are frequently seen in this patient population, especially adolescents, as is an increase in femoral anteversion and valgus malalignment of the lower extremity. Adaptations in gait, such as hip and knee external rotation and contractures of the hip abductors and iliotibial band, are also seen. Traditionally, the Q angle (Figure 10–3) has been used in the evaluation of patellofemoral symptoms. Many different methods of measuring this angle have been reported, and the high interobserver variability makes it of questionable usefulness.6,7 As described, the Q angle should be evaluated in both full extension and approximately 30 degrees of flexion because, in some cases, a laterally subluxated patella in full extension can falsely decrease the Q angle (the patella should be repositioned in the central sulcus before measuring the Q angle). My preference is to examine and measure the Q angle is full extension with the patella manually reduced in the trochlea with medially directed force on the patella; I call this the “thumb reduction test.” Ask the patient to contract the quadriceps, and you can see and feel the patella sublux laterally. Q angles in asymptomatic patients are 14 degrees in males and 17 degrees in females.8 Quadriceps wasting, especially of the vastus medialis, is common in longstanding patellofemoral symptoms. Recently, more emphasis has been placed on core muscle weakness, especially of the hip abductors, hip extensors, and pelvic stabilizers. Weakness in this group can be demonstrated by asking the patient to single-leg stand on the affected limb, which results in a pelvic drop on the contralateral side. In addition to poor pelvic support, dynamic internal rotation of the femur and dynamic valgus positioning of the limb can be observed. Activity-related swelling and, in particular, a joint effusion indicate more advanced disease. Palpation of the medial and lateral retinaculum can elicit pain. The lateral structures often are contracted (tested by attempting to reverse patellar tilt), whereas the medial soft tissues can be attenuated (e.g., chronic patholaxity of the medial patellofemoral ligament). Patellar mobility, tilt, and subluxation should be assessed and quantified medially and laterally. Normally the patella should be able to “glide” 30% of its width medially and laterally without the patient experiencing apprehension of a subluxation or dislocation. Catching with mobilization of the patella against the trochlea is suggestive of larger defects. Knee range of motion usually is preserved but may be inhibited by pain or large effusions in acute cases. The J-sign (the patient slowly extends the knee from full flexion, and the patella subluxes laterally once it leaves the constraints of the trochlear groove near full extension) may occur in normal patients but is exaggerated in patients with patellar maltracking. It often implies incompetence of the medial restraining structures, including the medial patellofemoral ligament.

Imaging studies

Useful tests that assist in determining the diagnosis are standard radiographs, including standing anteroposterior, 45-degree posteroanterior (Rosenberg), lateral, skyline (Merchant), and standard 54-inch axial alignment x-ray films. Radiographs are useful with any patellofemoral joint to determine joint space narrowing or osteoarthritis on a standard Merchant view. This view is taken at 45 degrees of flexion during which the patella is normally well engaged in the trochlea distally. It is not an effective view for assessing maltracking, which, when it occurs, is usually in the first 0 to 30 degrees of flexion from extension. The dislocated or subluxed patella in full extension travels medially as it travels distally, capturing the trochlea as it reduces. This is the clinical finding of a J-sign. Dejour et al9 showed the advantages of a true lateral radiograph in assessing trochlear dysplasia and patellar tilt not appreciated on the Merchant view.

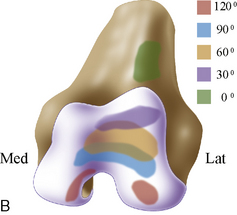

Assessment of articular cartilage injury is receiving more attention with newly developed imaging protocols enhanced by intravenous gadolinium as an indirect arthrogram. Although the gold standard for assessing articular injury remains arthroscopy, sensitivity and specificity greater than 90% can be obtained with high-resolution MRI scan using a standard 1.5-T magnet with appropriate orthogonal gantry tilting to surfaces of the trochlea and appropriate sequences.10,11 This is our preferred method for assessing articular cartilage injury to localize the site and size of chondrosis in the patellofemoral articulation.

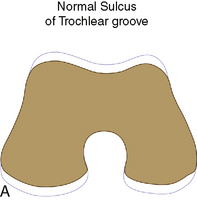

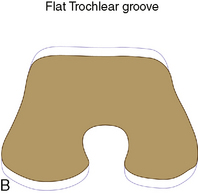

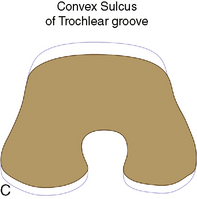

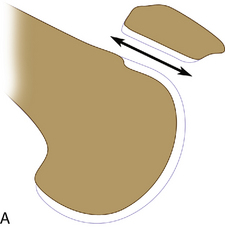

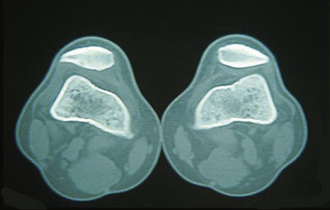

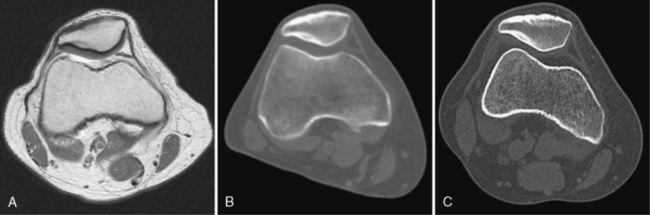

To accurately assess patella subluxation, spiral computed tomography (CT) of the patellofemoral joint is performed with the leg in full extension, once with the quadriceps relaxed and again with the muscle maximally contracted (Figure 10–4). It is especially helpful in determining dysplasia of the bony patellofemoral joint (Figures 10–5 and 10–6). CT also allows more precise evaluation of patellar and trochlear anatomy than the Merchant view (Figure 10–7). Accurate documentation of subluxation can be determined with the CT scan with clinical findings are difficult, especially in the obese patient.

Figure 10–4 Bilateral subluxed patellas noted on CT scan with quadriceps contracted with the knees in full extension.

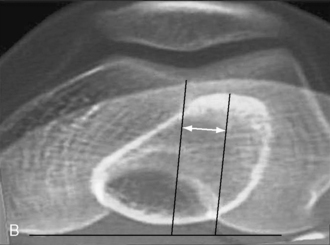

Figure 10–7 A, A high-resolution MRI scan with intravenous gadolinium utilized as an indirect arthrogram effect. Notice the intact full thickness nature of the lateral patellar articular cartilage. This 32-year-old woman has had a history of “chondromalacia” since the age of 12 years old. She has undergone multiple courses of physical therapy, taping, and bracing. She has been offered a patellar lateral arthroscopic release and has sought another opinion. B, This is a CT scan of the patella in a well reduced to position. Notice the thickening of the subchondral bone to the lateral patellar facet. This is indicative of chronic lateral maltracking, overload with remodeling of the subchondral bone. C, The patient contracting her quadriceps with the leg in extension. Notice the lateral subluxation of the patella. The patient requires isolated medial translation of the tibial tubercle accompanied by a patellar lateral retinacular release. The articular cartilage demonstrated in Figure 10–7A was normal, therefore there was no need for anterior translation of the tubercle.

The addition of intraarticular gadolinium contrast helps to outline any articular cartilage defects on the patella, trochlea, or both and the exact location and size. My preferred test for patellofemoral maltracking, locating the articular cartilage defect, and assessing dysplasia of the trochlea is a CT arthrogram performed with the quadriceps first relaxed and then contracted in the fully extended knee (Figure 10–8).

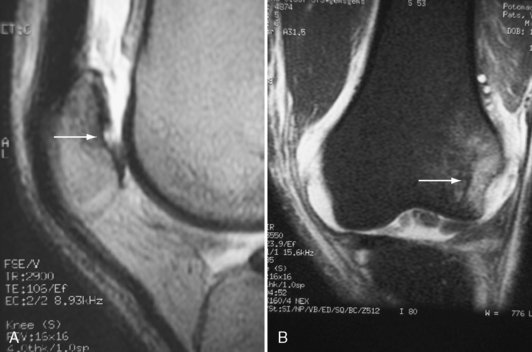

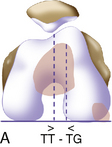

Furthermore, superposition of two CT images, one through the patellofemoral articulation and the other through the tibial tubercle, allows calculation of the tibial tubercle to trochlear groove (TT–TG) distance. The center of the trochlear groove and the center of the tibial tubercle are marked, and the medial to lateral distance between the two is measured (Figure 10–9). A TT–TG distance greater than 15 mm is considered normal; values greater than 20 mm are abnormal and should be considered for a tibial tubercle osteotomy (TTO).12 It is possible to use MRI obtained during routine knee evaluation to measure the TT–TG distance (Schoettle et al13 demonstrated the equivalency of CT and MRI TT–TG measurements) and the Caton-Deschamps measurement of patellar height (alta, infera, normal), thus providing additional information without added cost.14

Identify the pathomechanics: successful surgery

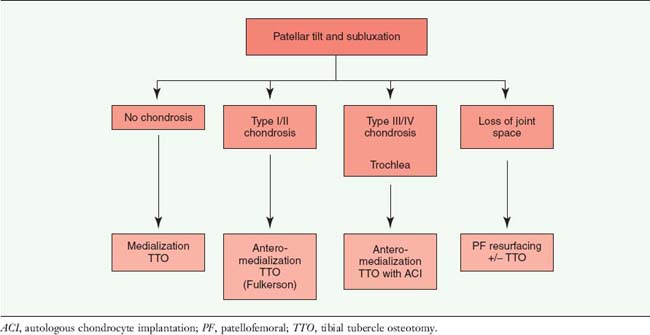

The primary factors that I have found to guide my treatment algorithm are patellar tilt, subluxation, and localization of the chondrosis (Table 10–1).

ACI, autologous chondrocyte implantation; PF, patellofemoral; TTO, tibial tubercle osteotomy.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree