Patellofemoral Complications Associated with Total Knee Arthroplasty

Patellofemoral complications once accounted for as much as 50% of complications after total knee arthroplasty (TKA).1 These statistics come from arthroplasties performed in the 1980s and early 1990s. With improvements in surgical technique and prosthetic design, the incidence has decreased but is still significant. Problems include pain after an unresurfaced patella, maltracking, fracture, prosthetic loosening, osteonecrosis, and prosthetic wear.

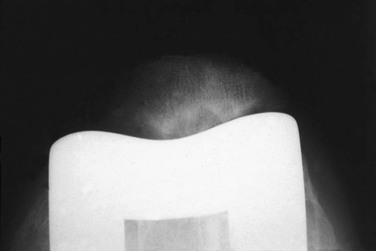

One of the persistent controversies in TKA is whether the patella requires resurfacing. I have more than 40 years of experience working with this question. In 1973, most prosthetic designs did not provide for even the possibility of patellar resurfacing of either trochlea or patella. In 1974 the first prostheses—one in the form of the duopatellar design—provided a femoral component with a trochlear flange and an optional polyethylene button for the patellar side of the patellofemoral joint.2 At that time, 80% of our patients had rheumatoid arthritis. In 1974, we resurfaced only 5% of the patellae in both patients who had rheumatoid arthritis and those with osteoarthritis. The patellae that were resurfaced were the ones having severe degenerative changes with exposed patellar bone at the time of arthrotomy. A 5-year review showed that 10% of the patients with rheumatoid arthritis had secondary degeneration of the patella with cystic changes, pain, swelling, and sometimes the recurrence of rheumatoid synovitis (Figure 6-1). By the end of the 1970s agreement was uniform within our group to resurface the patella in all patients with rheumatoid arthritis regardless of the operative findings.

Even in retrospect, we could not predict which patients with rheumatoid arthritis would have problems and which would not. I do not mean to say that an unresurfaced patella in these patients will always encounter difficulty. I have some patients with rheumatoid arthritis without a resurfaced patella who are still functioning well without patellofemoral symptoms more than 30 years after surgery.

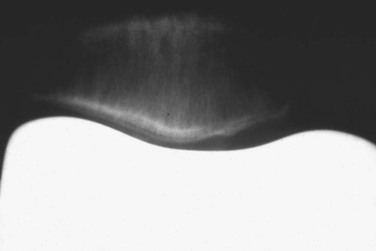

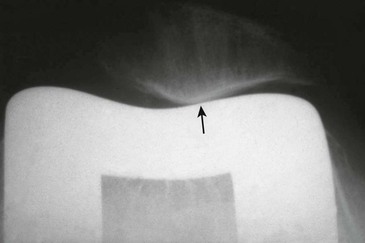

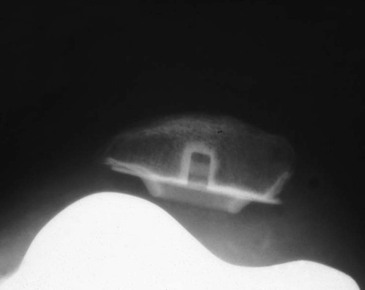

Patients with osteoarthritis fared better than those with rheumatoid arthritis (Figure 6-2). Patients who did have secondary degeneration of the patella after TKA usually had a slight maltracking problem. The result would be areas of focal wear causing pain and possibly leading to progressive degeneration of the bone and progressive subluxation (Figure 6-3). From this experience I developed certain selection criteria in the 1980s that led to selective patellar resurfacing in approximately 80% of patients with osteoarthritis and left 20% of patellae unresurfaced. The indications for not resurfacing included noninflammatory osteoarthritis. That meant that in patients with gout, pseudogout, or an inflamed synovium patellae were resurfaced. In addition, the patients would need to have congruent tracking of the patella on the preoperative skyline with maintenance of a joint space. No areas of exposed eburnated bone would be present at surgery. The unresurfaced patella would also have to track congruently with the trochlear flange of the prosthesis. Using these selection criteria, the 10-year survivorship of unresurfaced patellae was 97%.3 On the other hand, resurfaced patellae from that era were experiencing a higher incidence of complications, including accelerated wear of a metal-backed patella, potential wear and deformation of an all-polyethylene patella, patella stress fracture, and prosthetic loosening.

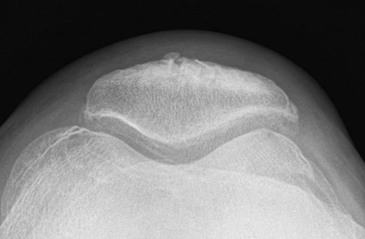

Second-decade evaluation of results showed that some patients with unresurfaced patellae could develop significant symptoms as late as 15 years after their arthroplasty and require secondary resurfacing. At the same time, improvements in prosthetic design and surgical technique were diminishing the complications seen with resurfacing. In addition, a patient with an unresurfaced patella might have pain that was attributed to the patellofemoral compartment but more likely did not originate from it. Unnecessary and unhelpful repeat surgery to resurface the patella could result. This situation prompted me to eliminate older patients and those with very low pain thresholds from the group that I might leave unresurfaced. For this reason, my incidence of not resurfacing the patella has diminished to less than 2% of cases. Today, if I do not resurface the patella, it is after a careful preoperative discussion with the individual patient about the pros and cons of this decision. The advantages of not resurfacing are the conservation of patellar bone, avoiding resurfacing complications, easy salvage, and permitting high patellofemoral forces to be placed on this articulation without concern for prosthetic wear in active patients. The disadvantages are the possibility of incomplete pain relief and the fact that as comparative reoperation rates for resurfacing became known, they appeared to favor resurfacing in most patients. The ideal candidate for nonresurfacing is probably the young, heavy, active male patient (Figure 6-4).

When considering not resurfacing the patella, always remember that the prosthetic geometry of the trochlear flange of the prosthesis can make a difference. Obviously a flange that is not anatomic and flat will not tolerate an unresurfaced patella as easily as one that is anatomic in shape. The reported results of nonresurfacing must be considered to be prosthesis-specific and not necessarily generic.

Maltracking of the patella associated with TKA is usually the result of several factors converging in the same patient. Causes of maltracking include residual valgus limb alignment, valgus placement of the femoral component, patella alta, poor prosthetic geometry, internal rotation of the femoral or tibial component, excessive patellar thickness, asymmetric patellar preparation, failure to perform a lateral release when indicated, capsular dehiscence, and dynamic instability.

Residual Valgus Limb Alignment

Valgus limb alignment after TKA is usually the result of excessive valgus placement of the femoral component. I think this occurs most often when the surgeon places the intramedullary alignment device for the distal resection into a hole made at the center of the intercondylar notch (see Chapter 3). Preoperative templating will show that on most radiographs a line down the center of the shaft of the distal femur will exit several millimeters medial to the true anatomic center of the notch. If the entry hole is made lateral to the true exit point, the amount of valgus imparted to the distal cut will be up to several degrees greater than indicated by the instrument. The resultant increased valgus to the limb alignment increases the Q-angle, encouraging lateral tracking of the patella.

Excessive Valgus Placement of the Femoral Component

Even if the surgeon counteracts valgus placement of the femoral component with some varus placement of the tibial component, correcting overall limb alignment, a valgus femoral component can compromise patellar tracking. The valgus placement shifts the most proximal portion of the trochlear flange medially so that the patella may not even be centered on the groove in full extension (Figure 6-5).

Patella Alta

Patella alta can affect tracking in a similar manner. In this situation, the patella is positioned higher than the top of the prosthetic trochlear flange in full extension and may not be funneled properly into the groove of the trochlea. The predicament of patellar tracking is accentuated when the trochlear flange of the prosthesis is both narrow and shallow (Figure 6-6).

Component Malrotation

Internal rotation of either the femoral or the tibial component can promote maltracking. On the femoral side this is caused by the fact that with internal rotation of the femoral component the trochlear groove is moved medially away from the natural mediolateral position of the patella. I believe the effect of internal rotation of the femoral component on patellar maltracking may be overestimated. Depending on prosthetic geometry, it takes approximately 4 degrees of rotation of the femur to move the trochlear groove 2 mm. The amount of internal rotation will therefore determine its influence (Figure 6-7).

The effect of rotation can be counteracted by undersizing the patellar component and shifting it medially, as well as moving the femoral component as far laterally on the distal femur as possible so long as prosthetic overhang is not created.

In summary, although femoral component rotation does have an effect on patellar tracking, as stated earlier, I think that femoral component rotation by itself is not as significant as thought by others. The major importance of femoral component rotation is to assist in the establishment of flexion gap symmetry. The technical details of determining femoral component rotation are discussed in Chapter 3.