Patellar Fractures: Open Reduction Internal Fixation

John H. Wilber

Paul B. Gladden

Indications/Contraindications

Operative management is the treatment of choice for the majority of displaced patellar fractures. Surgical options include open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF), partial or complete patellectomy, with the choice of treatment dependent on the fracture pattern and the amount of comminution. Although there is no widely accepted classification system for patellar fractures, most are based on an anatomic descriptive classification. Important factors include the location of fracture, direction of fracture lines, and the amount of comminution. In the AO/OTA classification, the patella is delineated as 45 and subdivided into A, B, or C depending on whether the fracture is extra-articular, partial articular without disruption of the extensor mechanism, or complete articular with disruption of the extensor mechanism. For the most part, 45B patella fractures are managed nonoperatively whereas 45A and 45C fractures require surgery.

The patella is an integral component of the extensor mechanism of the knee as well as an articular component of the knee joint. The patella’s position in the body and the nature of its role in lower-limb function cause it to be susceptible to injury. Traction forces that pull the patella cephalad are the result of several different vectors caused by contraction of the quadriceps muscle. The quadriceps muscle, extensor retinaculum, along with the iliotibial band, participates in knee extension. The undersurface of the patella, which articulates with the notch of the femur, has the thickest cartilage found in the body. It is this articulation that acts as a fulcrum for extension. Forces measured at the patellofemoral articulation can be over seven times body weight during routine activities such as stair climbing and squatting. Tensile forces can be well over 3,000 N. The importance of the patella for normal knee function cannot be overestimated. Patellectomy results in the loss of the patellar fulcrum, a decrease in the moment arm, and relative lengthening of the quadriceps. This can lead to instability of the knee, extension lag, atrophy of the quadriceps, and loss of extension strength. Therefore, whenever possible, the patella should be repaired rather than excised.

Total patellectomy is generally indicated when the patella is so severely comminuted that an acceptable reduction and stable fixation cannot be achieved with internal fixation.

Partial patellectomy is indicated for cases that have severe comminution of either the inferior or superior pole that is not amenable to ORIF techniques.

Partial patellectomy is indicated for cases that have severe comminution of either the inferior or superior pole that is not amenable to ORIF techniques.

ORIF is indicated for displaced patellar fractures that have fragments large enough to be reduced and stably repaired and is the treatment of choice for the majority of displaced patellar fractures in physiologically young patients. Many comminuted fractures can be salvaged. The goal of surgery is to achieve anatomic reduction of the articular surface with restoration of the continuity of the extensor mechanism. Displacement more than 3 mm and articular incongruity of more than 2 mm are considered strong indications for surgical treatment.

Contraindications and relative contraindications to surgical treatment include nondisplaced or minimally displaced stable fracture patterns. Also, contused or injured skin that precludes safe surgical approaches to the fracture, active infection involving the extremity with the patellar fracture, and medical conditions of the patient that would preclude safe surgical intervention are contraindications for surgery.

Preoperative Planning

An accurate history and careful physical examination should be performed. The mechanism of injury may explain the severity of injury as well as the fracture pattern. It is helpful to know whether the injury occurred as a result of a direct blow (e.g., a fall on the knee) or from resisted flexion of the knee resulting in a traction-type injury.

The physical examination must include a thorough evaluation of the extremity, with the surgeon looking for signs of direct trauma and swelling. The presence of fracture blisters, lacerations, abrasions, and contusions should be documented. It is essential to determine whether the fracture is open. Superficial or small wounds should be checked and if necessary carefully explored to determine whether they are in continuity with the fracture or the knee joint. In displaced patellar fractures, a visible or palpable defect is often noted between the fragments, although this may be masked by significant swelling, which develops rapidly. In some cases, a hemarthrosis is not apparent because of a large retinacular tear that allows blood to dissipate into the surrounding soft tissues. The absence of a hemarthrosis does not rule out a patellar fracture.

The continuity of the quadriceps mechanism is evaluated next. A painful, tense hemarthrosis often complicates this part of the examination. Aspiration of the knee with injection of a local anesthetic usually decreases pain. The patient is asked to contract the quadriceps mechanism and attempt to extend the knee fully. The ability to do this does not rule out a patellar fracture because the medial and lateral retinacula may still be intact, providing partial continuity of the extensor mechanism. However, the inability to lift the leg usually indicates that a patella fracture that tears the medial and lateral retinaculum exists. Gentle stress testing of the knee for stability should be carefully performed. Knee flexion should be avoided because this may further displace the fracture in addition to causing significant discomfort to the patient. The peripheral pulses and the compartments of the leg should be evaluated, and a neurologic examination performed.

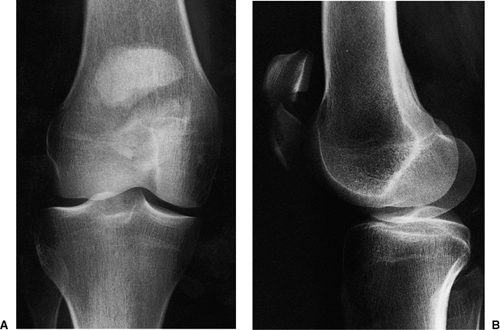

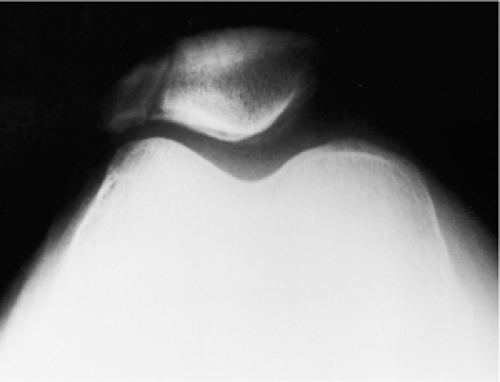

The initial radiographs to evaluate a painful knee following injury include anteroposterior (AP), lateral, and axial views of the patella. A supine AP radiograph is obtained, centered over the patella (Fig. 24.1). The lateral radiograph can be taken as a cross-table lateral, with the knee slightly flexed. For an axial view, a Merchant’s view is most easily and safely obtained in the injured patient (Fig. 24.2). The patient is placed supine on the x-ray table with the knee flexed 45 degrees over the end of the table. The x-ray beam is angled at 30 degrees from the horizontal, and the cassette is placed perpendicular to this x-ray beam 1 foot below the knee. Comparison views of the uninjured knee can be helpful in selected patients (i.e., those with a bipartite patella). Occasionally in patients with complex fracture patterns, a computed tomography (CT) scan is indicated.

Vertical fractures are often missed on both the AP and lateral views and are best visualized on the axial view. Larger displaced-fracture lines can be readily seen, although smaller nondisplaced-fracture lines are often obscured because of the superimposition of the patella on the femur in the AP view. In most cases, the fracture is more comminuted than is

apparent on the radiographic evaluation. Displacement more than 3 mm and articular incongruity more than 2 mm are indications for surgery.

apparent on the radiographic evaluation. Displacement more than 3 mm and articular incongruity more than 2 mm are indications for surgery.

Preoperative drawings should be performed for complex fracture patterns. Surgeons should make a tracing on both the AP and lateral views of the uninjured contralateral side and then superimpose the fracture lines from the injured side onto the normal template. The fixation should be drawn and the procedural steps carefully listed. The operating room should be informed of the equipment required based on the preoperative plan. Equipment needed for surgery usually includes various-sized pointed bone-reduction clamps, small curettes, wire cutters, benders, and wire tighteners, and small Kirschner (K) wires. Power drills and wire drivers will also be necessary. Small and mini fragment screws and instruments should be available.

Figure 24.2. Axial view of the patella showing a vertical fracture of the lateral facet of the patella. There is minimal displacement of the fragments. |

Surgery can be undertaken as soon as the patient has been prepared and appropriate preoperative plans completed. If the fracture is open, surgery must be done urgently. Closed fractures should be surgically addressed when the soft-tissue injury and the general condition of the patient permit.

Surgery

The patient is positioned supine on a standard operating table. Because there is a tendency for the leg to externally rotate, a small bump can be placed under the ipsilateral hip. A tourniquet is placed high on the involved thigh. The procedure can be done under a general or spinal anesthetic. Regional nerve blocks (femoral nerve block) can be very helpful to control postoperative pain. The patient is prepped in a standard fashion, and the leg is draped free by using an extremity drape. The limb is exsanguinated with a sterile Esmarch, and the tourniquet inflated to a pressure appropriate for the size of the leg and the patient’s blood pressure. Before inflating the tourniquet, the quadriceps is pulled distally to ensure that it is not trapped under the tourniquet, which can displace the patella proximally, making reduction more difficult. A sterile bump can be placed behind the knee, which allows the knee to flex 15 to 20 degrees. Appropriate antibiotic prophylaxis should be given before inflating the tourniquet.

The skin incision can be either transverse or longitudinal. A longitudinal incision is preferred when more proximal and distal dissection is necessary for the repair of a comminuted fracture and when later reconstruction procedures are anticipated. For cosmetic reasons, the transverse incision is preferred. It also avoids potential damage to the saphenous branch of the femoral nerve.

The incision is carried down through the subcutaneous tissue and the prepatellar bursa. A hematoma is usually encountered as soon as the bursa is opened, and it usually leads directly into the fracture site (Fig. 24.3

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree