Abstract

Participation in community life is a major challenge for most people with psychiatric and/or cognitive disabilities. Current assessments of participation lack a theoretical basis. However, the new International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) provides a relevant framework.

Aims

The present study used an ICF-derived assessment tool to activity limitations and participation restrictions in two groups of participants with disabilities linked to schizophrenia or traumatic brain injury respectively.

Methods

Twenty-six items (related to six ICF sections) were selected by reviewing the literature and gathering the clinician’s opinions and representatives of patient associations. These items, yielded an ordinal rating of activity limitations, participation restrictions and contextual factors (social support, attitudes and, systems & politics). Special attention was paid to contextual and environmental factors. The final checklist (called the Grid for Measurements of Activity and Participation, G-MAP) was administered to 16 participants with traumatic brain injury (the TBI group) and 15 participants with schizophrenic disorders (the SD group). Psychometric assessments of cognition and, neurobehavioural, psychological and psychosocial functioning were also performed.

Results

The internal consistencies for activity limitations (Cronbach’s alpha coefficient = 0.89) and participation restriction (Cronbach’s alpha coefficient = 0.89) were satisfactory. We did not observe any significant differences between the two groups in terms of the psychometric test results. The G-MAP scores demonstrated that the two groups were confronted with the same limitations in self care, domestic life, leisure and community life (i.e., the intergroup differences were not statistically significant in Mann-Whitney tests). However, interpersonal relationships and economic and social productivity appeared to be more severely limited in the SD group than in the TBI group. Similarly, participation restrictions in domestic life, interpersonal relationships and economic and social productivity were more severe in the SD group than in the TBI group.

Conclusion

G-MAP is a useful, feasible, relevant tool for performing a detailed, individualized assessment of participation restrictions in people with psychiatric and/or cognitive disabilities.

Résumé

De nombreuses personnes présentant des limitations d’activité liées à des troubles psychiques ou cognitifs voient leur participation à la vie communautaire singulièrement réduite. L’évaluation de leur participation reste difficile par manque de bases théoriques et d’outils d’évaluation portant sur le lien entre facteurs d’environnement, restrictions de participation et rôle de l’affection en cause. La CIF offre un cadre pertinent pour clarifier cette question.

Objectifs

Créer un document d’évaluation situationnelle dérivé de la CIF, apporter des informations sur les critères métrologiques et l’intérêt de cette grille, comparer limitations d’activité et restrictions de participation dans deux populations concernées par le handicap d’origine psychique et/ou cognitive : schizophrénie et traumatisme crânien, à l’aide de cet outil standardisé.

Méthode

Vingt-six situations de handicap regroupées en 6 catégories de la CIF (limitation d’activité, restrictions de participation, facteurs contextuels : soutien social, attitudes, systèmes et politiques) ont été sélectionnées à partir d’une analyse critique de la littérature et de la confrontation d’opinions de cliniciens, de consultants du milieu associatif. Une attention particulière est portée aux facteurs contextuels et d’environnement. La grille obtenue (Grille de Mesure de l’Activité et de la Participation : G-MAP) a été administrée à titre exploratoire au cours d’un entretien semi-dirigé à 16 patients traumatisés crâniens (TC) et à 15 patients souffrant de troubles schizophréniques (TS). Des évaluations psychométriques complémentaires (fonctionnement psychosocial, incapacités psychiques et cognitives) ont été effectuées.

Résultats

Les deux groupes obtiennent des scores équivalents pour les variables cognitives et psychologiques. La consistance interne des items de la G-MAP est satisfaisante pour les limitations d’activité comme pour les restrictions de participation (α de Cronbach = 0,89 pour les 2 dimensions). Les deux groupes présentent des limitations d’activité équivalentes pour les soins personnels, la vie domestique, les loisirs et la vie communautaire (tests de Mann-Whitney non significatifs). En revanche, le groupe TS semble plus en difficulté que le groupe TC dans les relations interpersonnelles et la productivité économique et sociale. Les restrictions de participation touchent également davantage le groupe TS que le groupe TC dans le domaine de la vie domestique, des relations interpersonnelles et de la productivité économique et sociale.

Conclusion

Dans cette étude exploratoire, les deux groupes se différencient davantage sur les restrictions de participation que sur les limitations d’activité, ce qui suggère une forte influence des facteurs d’environnement. La G-MAP s’est avéré être un outil pertinent, fiable et adapté à l’évaluation détaillée et individualisée des restrictions de participation d’une personne dans son environnement. L’étude se poursuit sur un plus grand nombre de sujets.

1

English version

Although France’s 2005 Disabled Persons Act does not define psychological and/or cognitive disability in adults per se, it is based on the fact that activity limitations and participation restrictions result from cognitive and/or psychological impairments of functioning and thus create disabling situations. This is observed in many diseases: mental handicap, chronic psychosis, brain disorders (such as stroke and traumatic brain injury [TBI], neurodegenerative disorders, dementia and Alzheimer’s disease). Despite progress in patient management and treatment, psychological and cognitive disabilities constitute a high-priority public health issue, in view of:

- •

the number of people affected;

- •

the intensity of the suffering experienced by these people and by their families and friends and;

- •

the considerable social cost of providing long-term institutionalisation (at least in France) or human assistance for maintaining personal and social independence.

Traumatic brain injury and schizophrenia are very different conditions in terms of their aetiology, disease mechanism and clinical expression but are both responsible for frequent, severe psychological and/or cognitive disabilities. For example, it is known that fewer than half of the victims of severe TBI are able to perform complex activities of daily and social living on their own and that 12% will spend the rest of their life in an institution . Family life, sexuality , returning to work or finding a job , access to leisure and, more generally, the ability to live independently and contribute to society are seriously compromised by the consequences of TBI. Schizophrenia is the eight most frequent cause of disability in the 15–44 age group in Europe – ahead of several major medical conditions such as cancer or asthma – and severely perturbs integration into the community. In Europe, 80% of people with schizophrenia are unemployed and only 17% are married , with little variation from one country to another . People with schizophrenic disorders report a significant reduction in their quality of life for leisure and social, family and work relationships, relative to people free of mental conditions .

In fact, identifying difficulties in social integration has always been more difficult for people with psychological and/or cognitive disabilities than for people with physical disabilities. Indeed, the term “invisible handicap” is very apt! Barriers to integration are more often related to people’s attitudes (the prejudice of a shop worker or an employer and the views of disability held by society in general) and, in some cases, public policies than to architectural barriers .

The evaluation of these situations by administrative and social services (questionnaires for determining eligibility for disability benefits or home help, regional healthcare monitoring offices and expert opinions in legal cases, for example) remains challenging and controversial. Cognitive, psychological and behavioural disorders are not specifically evaluated. The particular features of these difficulties as a function of the underlying condition and the influence of environmental factors are also poorly known; the literature data do not enable us to say whether different conditions are related to a given participation restriction to the same extent.

The International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) has radically changed theoretical models of disability – notably by taking into account the true degree of involvement in life situations (participation) on one hand and contextual and environmental factors on the other. As such, the ICF constitutes a relevant framework for clarifying the above-mentioned issues. At this point, it is worth briefly reviewing the major changes prompted by introduction of the ICF. The ICF addresses the issue of disability in terms of two components: personal functioning and environmental factors. Personal functioning is examined through an organic component (body functions and structure) and through activity and participation. This arbitrary separation enables one to focus more easily on the activity (the tasks that a person can perform) and its corollary (activity limitations, which are the difficulties encountered by a person in the execution of certain activities or tasks). Concerning participation (i.e., a person’s involvement in a real life situation), the ICF adopts the concept of “participation restrictions”, which are problems that a person may encounter when involved in a real-life situation. We can address this topic in a simplified manner by stating that an activity corresponds to the person’s ability to perform a task (i.e. being able to do something – the concept of “capacity”). Participation reflects the person’s actual involvement in the activity and whether he/she performs the task effectively (actually doing something – the concept of “performance”). The result is linked to environmental (physical and relational) components and personal factors (related to the person’s history, his/her life habits and preferences, etc.). Of course, the ICF is a classification and thus seeks to describe human functioning in the finest detail. The characteristics of human functioning vary greatly; we considered that adapting the concept to one person in particular was highly relevant when addressing functioning.

In the present study, the ICF enabled us to take account of activity limitations and participation restrictions reported by the interviewee on one hand and environmental factors (physical factors, such as the distance to town from home) and contextual factors (relationships, work and daily life) on the other.

One of the objectives of the present research was to derive an assessment checklist from the ICF. The goal was provide information on the metrological criteria for a standardized checklist, measure the checklist’s value and describe the reported activity limitations and participation restrictions. The present study assessed people suffering from schizophrenic disorders or TBI and who present a psychological and/or cognitive disability.

An extract from an interview with Mr F ( Appendix 3 ) will enable the reader to familiarize him/herself with the concepts of activity limitation, participation restriction and environmental factors.

1.1

Materials and methods

1.1.1

Development of the assessment tool

The first step in identifying life difficulties faced by patients with disabilities as a result of TBI or a schizophrenic disorder consisted of a literature review and the analysis of suggestions from our group’s clinicians and researchers, who came from a variety of backgrounds: physical and rehabilitation medicine (PRM), psychiatry, occupational therapy, psychology and neuropsychology. The second step consisted in better defining the content and boundaries of the concepts of psychological and/or cognitive disability. To this end, we exploited the results of an earlier (unpublished) study performed in 2007 with the WHO Collaborating Centre in France for the International Classifications (the former Centre national d’études et de recherche sur les handicaps et les inadaptations) and an occupational therapy training institute. We used the ICF checklist in various local institutions and services (a rehabilitation centre, a care home, foster families, a specialist clinic, social services for disabled adults, etc.) but also directly questioned people suffering from the consequences of TBI or psychiatric disorders. We were thus able to collate transcripts of the real-life activity limitations and participation restrictions experienced by these people. Under the supervision of one of the authors (C. B.) and a sociologist (C. B.) from the WHO Collaborating Centre in France for the Family of International Classifications, we matched this dataset to activities to which the ICF refers. It quickly became clear that evaluating the role of personal and environmental factors was going be both difficult and decisive for building an effective tool. We leveraged our previous work on personal and environmental factors when selecting the ICF categories on which the tool was then built.

The third step consisted in comparing the selected ICF categories with feedback from representatives of the French National Alliance on Psychiatric Disorders (Union nationale des amis et familles de malades psychiques) and the French National Brain Injury Alliance (Union nationale des associations de familles de traumatisés crâniens). The very well-argued and often heated discussions that followed each presentation of an ICF category enabled us to select and classify life situations in a consensual manner (and always by reference to ICF chapters). During this third phase (and in order to better agree on the environmental and personal factors to be studied further), a working group headed by one of the authors (MK, a specialist in the psychology of healthcare and the evaluation of coping processes and social support) worked on this particular aspect and suggested a number of specific variables (such as the type of human assistance received, the type of person providing assistance and the patient’s level of satisfaction with that assistance). There was a focus on the notion of social support network, i.e. a person’s feeling that he/she is or is not being helped, protected and valued by family and friends.

In terms of environmental factors, we considered quantitative and qualitative aspects of social support network. The quantitative aspect corresponds to social support availability (SSA): the number of people who were ready (according to the interviewee) to help him/her at difficult times, i.e. people on whom the interviewee believes he/she can count. The qualitative aspect relates to satisfaction with social support (SSS). This is defined as a person’s stated satisfaction with the social support that he/she has obtained; the situation is only satisfactory when the support a person receives (or thinks he/she receives) is adequate with respect to his/her expectations and needs. Some people may not receive any help and may be perfectly satisfied with that situation.

The SSA score takes account of the number of categories of people likely to provide real support or assistance (between 0 and 3 categories: family, friends, acquaintances, healthcare and social services staff, etc.) in each of the situations mentioned.

A person’s SSS was scored on a 5-point Likert scale: very dissatisfied, somewhat dissatisfied, neither satisfied nor dissatisfied, somewhat satisfied and very satisfied.

Each environmental factor (systems, services and public policies and attitudes towards the interviewee) was classified as a facilitator, a barrier, both or neither.

This work resulted in the elaboration of a prototype 26-item checklist that was tested on 10 subjects. This initial testing prompted the reformulation of several questions in the interview guide and modification of the scoring system. The final Grid for Measurements of Activity and Participation (G-MAP; Appendix 1 ) featured 26 items, each of which was associated with a rank (ordinal score) for activity and participation. The G-MAP is filled out at the end of a semi-structured interview built around a number of key questions (some of which are presented in Appendix 2 ).

All the interviews were filmed by a single interviewer/evaluator. Some interviews lasted over four hours. The responses were scored by two different evaluators at different times (the interviewer/evaluator him/herself and then a second evaluator watching a video recording).

At the end of each interview, we asked the interviewee to give his/her general opinion on the value of the G-MAP assessment.

1.1.2

Psychological and behavioural variables

In order to characterize the study participants with respect to the general population and literature data, psychometric evaluations of cognitive function, social support and self-esteem were also performed:

- •

cognitive function, including processing speed: WAIS-III coding ; working memory: letter-number sequencing in WAIS-III; episodic memory: a 16-item free/cued recall test ; executive function: the Stroop test ; social cognition: the attribution of intentions test ;

- •

psychological function, including self-esteem: the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale, ; social support availability and satisfaction: the 6-item Social Support Questionnaire-6 ;

- •

specific tests in the schizophrenic disorders (SD) group: the Global Assessment of Functioning Scale and the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale ;

- •

specific tests in the TBI group: the Neurobehavioral Rating Scale-Revised, Revised Neurobehavioral Scale NRS-R .

1.1.3

Participants

The evaluation concerned 16 TBI victims (mean time since TBI: 87 months; range: 5–220 months) and 15 patients with clinically stable, chronic, schizophrenic disorders (as diagnosed at a consultation or during hospitalisation; mean time since onset: 110 months; range: 4–230 months).

The TBI victims were invited to participate in the study:

- •

during a consultation in a university hospital medical rehabilitation service and;

- •

at the hospital’s evaluation, re-training and socioprofessional advice unit (UEROS).

The inclusion criteria were as follows: age between 16 and 65 inclusive, the ability to speak French fluently, open or closed TBI (the severity of which was defined by the initial Glasgow Scale score) and the provision of written, informed consent. Subjects presenting marked motor and/or sensory impairments or a history of psychiatric disorders were not included in the study.

Participants suffering from schizophrenic or schizoaffective disorders (according to the DSM-IV-TR criteria ) were contacted individually in a specialist hospital. The inclusion criteria were as follows: age between 16 and 65 inclusive, the ability to speak French fluently, the absence of on-going psychotic episodes, stable symptoms, a stable medication regimen (for at least the previous month) and the provision of written, informed consent. The consent form was presented after the investigator had explained the research study’s objectives and design (i.e. a semi-structured interview on the various difficulties potentially encountered in daily life), its procedures (a recorded interview) and the professional credentials of the people running the study. Only one person declined to be interviewed.

Patients being treated with electroconvulsive therapy or transcranial magnetic stimulation and those presenting a major episode of depression, dependence on alcohol or another psychoactive substance (according to the DSM-IV-TR criteria) or a history of neurological problems (such as head injury and/or brain damage) were excluded from the study. At the time of the study, five patients were in hospital and 10 were been monitored as outpatients.

1.1.4

Statistical analyses

The internal consistency of the G-MAP’s activity limitation and participation restriction scores was evaluated by calculating Cronbach’s α coefficient. Intergroup comparisons of the various cognitive and psychological test scores and G – MAP’s activity limitation and participation restriction scores were performed using a Mann-Whitney U test. The threshold for statistical significance was set to P < 0.05.

1.2

Results

Table 1 shows the participants’ clinical characteristics and cognitive and psychological test scores. Most of the participants were single men. Although the mean age was higher in the SD group than in the TBI group, this difference was not statistically significant. With respect to recently collected normative data for France , the cognitive tests showed normal or slightly subnormal mean performance levels for most of the measured functions. In particular, the low WAIS III coding score (−1.7 SD) suggested significant cognitive slowing. The self-esteem scores were within the normal range. On the whole, the results were very similar in the SD and TBI groups, with the exception of a longer mean Stroop test completion time, a lower SSA score, a lower SSS score and slightly lower self-esteem in the SD group. However, these differences were not statistically significant.

| SD | TBI | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | 15 | 16 | |

| Age | 42.8 (11.9) | 31.6 (10.2) | 0.28 |

| Gender (males/females) | 8/7 | 14/2 | 0.06 |

| Educational level | |||

| Primary | 3 | 4 | |

| Secondary | 7 | 4 | |

| Higher | 5 | 8 | |

| Living as a couple | 2 | 4 | |

| PT number memory | 7 (2.6) | 7 (3.2) | 0.48 |

| PT coding | 4.3 (1.9) | 5.2 (2.7) | 0.36 |

| PT 16-item free/cued recall | |||

| Free recall | 10.6 (2.1) | 11.1 (1.8) | 0.33 |

| Total | 15.6 (0.9) | 15.7 (0.6) | 0.08 |

| PT Stroop test | 89.4 (57) | 62.3 (38.5) | 0.06 |

| PT attribution of intentions | 45.5 (10.4) | 52.1 (8.5) | 0.14 |

| PT self-esteem | 28.2 (7) | 32.5 (5.2) | 0.14 |

| PT social support | |||

| Availability | 11 (8) | 18.2 (10.7) | 0.07 |

| Satisfaction | 22 (10.1) | 30.5 (7.1) | 0.10 |

| STSD GAF | 45.6 (18.7) | ||

| STSD PANSS | |||

| Positive scale | 25.1 (7.6) | ||

| Negative scale | 31.5 (6.8) | ||

| General scale | 58.5 (12.1) | ||

| STTBI NRS-R | 11 (5.2) | ||

In the G-MAP, the internal consistency of the activity limitation and participation restriction scores (evaluated for the set of items as a whole) was satisfactory, with a Cronbach’s α coefficient of 0.89 for each of these two dimensions. For activity limitations, the items in each of the six categories (please refer to the interview checklist for details) were generally homogeneous: the Cronbach α coefficients ranged from 0.40 (“community life”) to 0.80 (“social productivity”). For participation restrictions, the internal consistency of the various categories was lower; Cronbach’s α coefficient ranged from 0.17 (“community life”) to 0.77 (“self care”).

Table 2 presents the mean activity limitation and participation restriction scores for each of the 26 G-MAP items. The participation restrictions were severe for balancing the domestic budget, spousal and sexual relationships, educational activities, paid employment, non-remunerative employment and all the “community, social and civic life” items: engaging in charitable organizations, service clubs or professional social organizations, civic life, voting, religion and spirituality. Participation restrictions were present but less severe for relationships with parents, siblings, friends and acquaintances and for leisure activities. The “self care” and “domestic life” categories were less affected.

| ICF category | Items | AL SD | AL TBI | AL Total | PR SD | PR TBI | PR Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self care | Hygiene | 0.00 | 0.63 | 0.32 | 0.33 | 0.19 | 0.26 |

| Eating | 0.13 | 0.19 | 0.16 | 0.53 | 0.19 | 0.35 | |

| Looking after one’s health | 0.53 | 0.25 | 0.39 | 0.47 | 0.31 | 0.39 | |

| Domestic life | Dressing, laundry | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.47 | 0.19 | 0.32 |

| Housework | 0.47 | 0.13 | 0.29 | 0.67 | 0.19 | 0.42 | |

| Moving around outside | 0.73 | 0.19 | 0.45 | 0.73 | 0.31 | 0.52 | |

| Managing a budget | 0.80 | 0.50 | 0.64 | 1.00 | 0.63 | 0.81 | |

| Acquisitions, shopping | 0.47 | 0.13 | 0.29 | 0.60 | 0.50 | 0.55 | |

| Interpersonal interactions and relationships | Parents, siblings, children | 0.40 | 0.25 | 0.32 | 0.64 | 0.44 | 0.53 |

| Spouse/partner (if appropriate) | 1.07 | 0.31 | 0.68 | 1.87 | 1.47 | 1.67 | |

| Sexual relationships | 0.73 | 0.06 | 0.39 | 1.67 | 1.00 | 1.32 | |

| Friends | 0.53 | 0.00 | 0.26 | 1.20 | 0.25 | 0.71 | |

| Acquaintances | 0.33 | 0.19 | 0.26 | 0.87 | 0.56 | 0.71 | |

| Strangers | 0.53 | 0.19 | 0.35 | 1.00 | 0.56 | 0.77 | |

| Economic and social productivity | School, training, education | 1.43 | 0.63 | 1.00 | 2.00 | 1.81 | 1.90 |

| Looking for work/training | 1.29 | 0.44 | 0.83 | 1.50 | 0.75 | 1.10 | |

| Paid work | 1.20 | 0.50 | 0.84 | 1.73 | 1.44 | 1.58 | |

| Voluntary work | 0.80 | 0.25 | 0.52 | 1.67 | 1.19 | 1.42 | |

| Financial independence | 0.73 | 0.56 | 0.65 | 1.07 | 1.31 | 1.19 | |

| Leisure | Indoor (TV, card games) | 0.13 | 0.06 | 0.10 | 0.87 | 0.50 | 0.68 |

| Outdoor (sports, walking) | 0.47 | 0.06 | 0.26 | 1.13 | 0.50 | 0.81 | |

| Group activities (restaurants, games) | 0.73 | 0.31 | 0.52 | 1.27 | 0.94 | 1.10 | |

| Community and civic life | Charities and clubs | 1.07 | 0.38 | 0.71 | 1.80 | 1.81 | 1.81 |

| Spirituality | 1.20 | 1.19 | 1.19 | 1.27 | 1.50 | 1.39 | |

| Administrative procedures | 0.93 | 0.50 | 0.71 | 1.13 | 0.69 | 0.90 | |

| Voting | 0.27 | 0.00 | 0.13 | 1.40 | 0.81 | 1.10 | |

Table 3 presents the mean (SD) scores for activity limitations and participation restrictions in the six G-MAP categories. Activity limitations were above all present for “productivity” (notably financial independence) and “community life” (notably spiritual life). In contrast, activity limitations were minimal for “self care”. The “domestic life”, “interpersonal interactions and relationships” and “leisure” categories fell between these two extremes. The activity limitations were more marked for the interpersonal relationships ( P = 0.006) and “productivity” ( P = 0.011) categories in the SD group than in the TBI group. For “self care”, leisure and “community life”, the mean scores were very similar in the two groups (with a non-significant difference in a Mann-Whitney U test). Likewise, participation restrictions for interpersonal relationships ( P = 0.005), “productivity” ( P = 0.012) and “domestic life” ( P = 0.045) were more severe in the SD group than the TBI group. Hence, participation restrictions were always more marked in participants suffering from schizophrenic disorders. However, it is noteworthy that the “participation restrictions” ranking was exactly the same in the two groups.

| Personal care | Domestic life | Interpersonal relationships | Economic and social productivity | Leisure | Community and civic life | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Activity limitations | ||||||

| DS | 0.22 (0.30) | 0.52 (0.51) | 0.60 (0.48)* | 1.11 (0.64)* | 0.44 (0.54) | 0.63 (0.45) |

| TBI | 0.17 (0.42) | 0.21 (0.31) | 0.17 (0.17)* | 0.48 (0.53)* | 0.15 (0.24) | 0.39 (0.33) |

| P | 0.233 | 0.079 | 0.006 | 0.011 | 0.106 | 0.116 |

| Participation restrictions | ||||||

| DS | 0.51 (0.49) | 0.69 (0.46)* | 1.21 (0.35)* | 1.64 (0.27)* | 1.09 (0.68) | 1.40 (0.32) |

| TBI | 0.23 (0.54) | 0.36 (0.34)* | 0.70 (0.47)* | 1.30 (0.38)* | 0.65 (0.58) | 1.20 (0.43) |

| P | 0.052 | 0.045 | 0.005 | 0.012 | 0.062 | 0.202 |

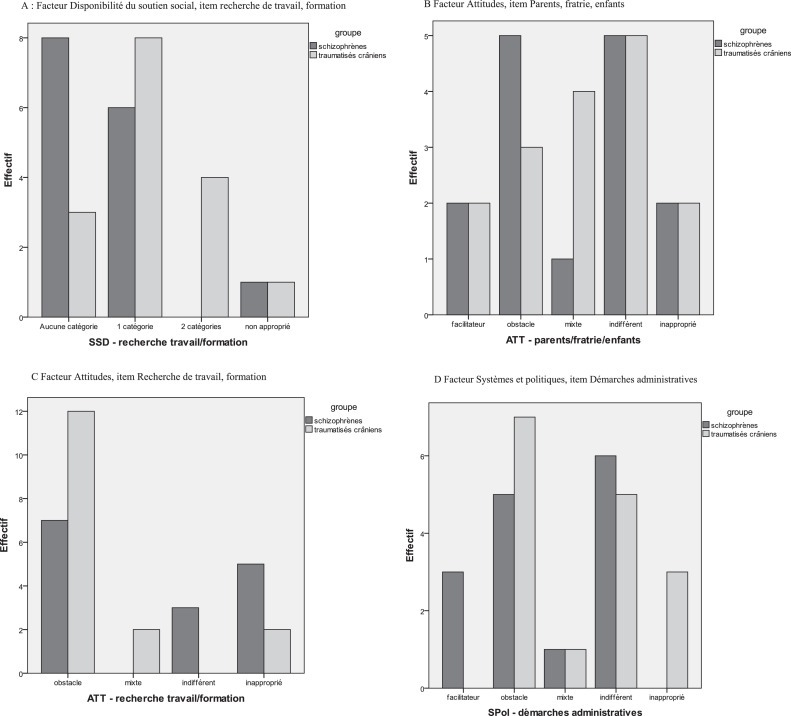

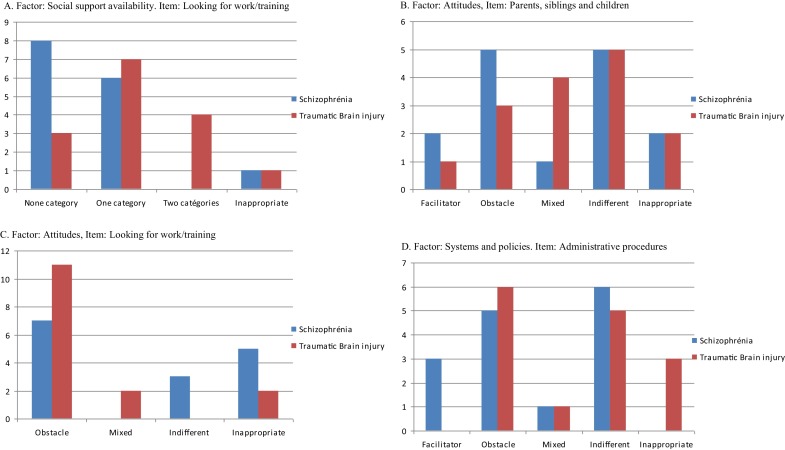

The environmental factors “interpersonal interactions and relationships”, “attitudes” and “services, systems and policies” were analyzed descriptively for each of the 26 items. The score distribution varied strongly as a function of the items and subjects; this demonstrates the relevance of the checklist for a detailed, personalized assessment. The distribution often differed when comparing the two groups, which suggests that the effect of environmental factors varies according to the aetiology. An exhaustive analysis would be fastidious, given the number of factors and the number of items . Fig. 1 provides a few examples ( Fig. 1 ). Considering the G-MAP’s SSA factor, a larger number of social support categories was cited by the SD group than by the TBI group. In contrast, the TBI group mainly cited the “healthcare professionals” category (see Fig. 1 A, for example) as the most important category. In terms of the SSS factor, all types of response (from ‘very dissatisfied’ to ‘very satisfied’) were observed in the two groups and there was no particular predominance. The “attitudes” factor had a generally moderate role and was twice as likely to be rated as a facilitator than as a barrier. However, there were large inter-individual differences (for the “parents’, siblings’ and children’s attitudes” item, for example [ Fig. 1 B]). For the “seeking work or training” item, participants in the TBI group stated that attitudes were predominantly barriers ( Fig. 1 C). In contrast, participants in the SD group were indifferent to the above-mentioned attitudes. It is noteworthy that this item was never considered to be a facilitator. The “services, systems and policies” factor clearly had a more significant role and was variously judged to be a facilitator (for “domestic life”), a barrier (for “interpersonal relationships” and “productivity”) or both (for “leisure”). The facilitating effect of “administrative procedures” was mentioned by participants in the SD group but not those in the TBI group ( Fig. 1 D). The same difference was seen for the “financial independence” item.

1.3

Discussion

The present study sought to evaluate the relevance of the ICF’s theoretical model in a detailed, personalized analysis of the social integration difficulties faced by people with psychological and/or cognitive disabilities. We also took account of the role of the medical condition, as described by the interviewees. The ICF essentially focuses on the consequences of disability and does not imply direct causality.

However, we considered that it was important not to totally ignore the role of the medical condition and the putative link between the underlying condition and its consequences. Indeed, we found that a certain number of interviewees:

- •

were very well aware of their difficulties;

- •

talked about these difficulties freely and;

- •

knowingly adapted to this situation ( Appendix 3 ).

Despite the very preliminary nature of the present study, our results indicated that:

- •

the data agreed with the opinions held by clinicians and representatives of patient associations, which is an argument in favour of the validity of the assessment tool’s content;

- •

taking account of environmental factors and specific aspects of a psychological and/or cognitive disability facilitates the provision of new information that is more accurate and more personalized than that provided by literature questionnaires – most of which were designed empirically or are based on other theoretical models.

Traumatic brain injuries and schizophrenic disorders were chosen here to illustrate the ICF model’s ability to analyze the same consequences (in terms of activity limitations and participation restrictions) for very different medical conditions and impairments. We intend to study other clinical situations in the future.

In the study population, activity limitations and participation restrictions primarily concerned productivity, such as looking for (or returning to) paid or non-remunerative employment, training and financial independence. It is well known that professional activity is one of the most important factors in the reintegration of TBI victims, since it provides financial independence, self-esteem, social integration and quality of life . The return to work is often considered as a return to psychosocial normality and marks the successful rebuilding of the person’s identity. Indeed, patients have great expectations in this respect . In industrialised countries, several TBI-specific back-to-work programmes have been implemented, including the UEROS network in France and holistic programs in the USA . Similar programmes are being developed for people suffering from chronic schizophrenic disorders . The programmes take account of impairments that restrict work capacities and there are specific rehabilitation measures for cognitive and behavioural impairments . By emphasizing the importance of environmental factors, our study provided novel information that complements the results of conventional surveys. Social support was stated as being available for some items (such as education, training and job seeking) by participants in the TBI group – perhaps as a positive effect of the UEROS programme – but was judged to be insufficient by participants with chronic schizophrenic disorders. The attitudes held by the general public and employers (considered to be a barrier by all the TBI victims) constitute a telling example of this. However, the marked inter-individual variability and inter-item variability are especially noteworthy. Now more than ever, professional integration programmes must take account of the different facets of person’s life situation.

The activity limitations and participation restrictions also applied to community life (i.e. involvement in voluntary organisations and clubs, administrative procedures and civic, religious and spiritual life). The scientific and medical literature accords less importance to these fields and data are scarce – which enhances the value of our present results. However, the very low value of Cronbach’s α coefficient for this category (0.17) suggests that it is heterogeneous and should be interpreted with caution until data for the general population become available. Indeed, it would be interesting to collect validated data in the general population in order to establish the extent to which integration problems are related to (for example) the high complexity or poor availability of support schemes, the poor attribution of resources or, more generally, the economic problems encountered in today’s society.

A study in healthy controls (with validation of the selected categories and items) is underway.

In the “economic and social productivity” and “community, social and civic life” categories, participation restrictions were generally more severe than the activity limitations. This suggests that the participants considered that the environment hardly acts as a facilitator: they would be able to do something (if pushed) but do not attempt to do so!

Lastly, participation restrictions were also more marked than activity limitations for interpersonal relations (notably spousal and sexual relationships) and leisure, suggesting that the participants considered that the environment could be a barrier. However, our analysis of the data on the four environmental factors did not enable us to identify a causal relationship for any given factor in particular; the situations are very individualized and vary from one person to another. It would be interesting to adopt a therapeutic approach that takes account of the family system as a whole (the neurosystems approach, for example ).

In view of the small sample size, it was not possible to draw definite conclusions on the specificity of participation restrictions as a function of the underlying medical condition (TBI vs. schizophrenia). In the present work, the underlying condition was merely a way of designating the two study groups. In the spirit of the ICF, the underlying condition is not, of course, the “cause”. Schizophrenia and TBI translate into a certain way of life – a certain way of “functioning” that can be described objectively through the activities that people are able (or not able) to perform.

The TBI participants appeared to have a clearer view of how social support can be organised. They also had a higher opinion of the efficacy of this support (in a greater variety of categories) than people suffering from schizophrenic disorders did. The TBI group was also more satisfied with the support that they actually received. This is undoubtedly related to the fact that most of the interviewees knew about or were participating in a UEROS programme and thus may indicate inclusion bias.

On the whole, activity limitations and participation restrictions appeared to be more severe in the SD group than in the TBI victims. In contrast, the cognitive test results were almost identical in the two groups. This observation suggests that:

- •

there was a difference between the two groups in terms of how they modulated or coped with their impairments and;

- •

the impairments in schizophrenia are not exclusively cognitive.

However, the difference appears to be purely quantitative, since the G-MAP checklist did not reveal any disease-specific restrictions or those due to the presence of a medical condition. This last point agrees with the fact that the ICF focuses on the interaction between the different fields on one hand and personal functioning on the other. The G-MAP checklist accurately reports on individual needs in terms of compensation, human assistance and financial assistance and could therefore be of significant value to the social services running these operations. The G-MAP checklist appears to be highly compatible with the procedure currently used by county council social services in France to attribute compensation and could provide some valuable, additional information.

Of course, the impact of the present pilot study should not be over-extrapolated, in view of the sampling bias and the limitations of the assessment tool (which has not yet been fully validated). The data collection procedure, the inter-observer reproducibility, the sensitivity to change and to demographic variables (notably age and educational level), the role played by certain factors (such as the participants’ awareness of their medical condition) is now being documented. The distinction between activity limitations and participation restrictions is difficult to score for some items, such as family relationships, sexuality and spirituality. Normative data in healthy control populations would be useful and are now being collected. Much larger samples will, of course, be necessary for going beyond an individual, personalized assessment and highlighting some general trends. We intend to pursue this work because our preliminary results appear to be encouraging. “Functioning” (as defined by the ICF) certainly appears to result from a dynamic interaction between the functional and social consequences of a person’s health problems on one hand and environmental factors on the other. In fact, the environmental factors interact with all the components of functioning and disability. This notion of interaction between individual and environmental dimensions as a guide to a disability situation raises questions about the nature and influence of environmental factors that facilitate or prevent social participation.

Our present analysis of selected environmental factors showed that the latter are sensitive and discriminant. Furthermore, the selected environmental factors were readily understood by the participants and are relevant – suggesting face validity. At the end of each interview, each interviewee was asked to give his/her opinion on how appropriate the questions were. A large number of people stated that they had never been asked this type of question before and that the questions were thought-provoking. On the basis of these interviews, our general impression is that the participants identified quite closely with the various difficulties resulting variously from environmental factors, personal factors, difficulties in doing or participating in an activity and the conjunction of several fields.

The inter-item variability in the scores for these factors suggests their impact depends on the field of disability and emphasizes the relevance of an item-by-item evaluation (rather than a general evaluation). We consider that item-by-item evaluation provides an accurate description of the interviewee’s actual functioning.

This result supports the ICF model , and provides more information than the tools generally used to evaluate a disabled person’s reintegration into society. The issue of personal factors remains and we suspect that they may have a significant role in psychological disability situations. Although this aspect is not addressed in the ICF, we invited each interviewee to draw their family’s genogram at the beginning of each interview. This information was very frequently “coupled” to the interviewee’s statements, in order to provide more precise information or expand on an answer.

1.4

Conclusion

France’s 2005 Disabled Persons Act defines disability as “any limitation or participation restriction in life in society… resulting from a substantial alteration… in one or more cognitive or psychological functions”.

Seven years on, there is still relatively little accurate information in the literature concerning the social and professional integration of people with cognitive or psychological disabilities, when compared with people with physical disabilities. The ICF’s multidimensional model appears to be a very valuable, relevant theoretical framework for developing research in this field. We intend to continue our validation of the G-MAP checklist, which appears to be compatible with existing procedures in France and is well suited to detailed, individualized assessments of participation.

Disclosure of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest concerning this article.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by the French Ministry of Research (grant 2008/90). The authors wish to thank J. Delbecq, F. Weber and all the people who worked on the call for tenders. The authors also wish to thank MC. Cazals (Vice-Chairman of the UNAFTC) and H. Roustan (Chairman of the Gironde section of the UNAFAM) for making themselves available and providing advice and encouragement and Dr X. Debelleix for help with patient recruitment.

2

Version française

La loi du 11 février 2005, sans pour autant définir le handicap d’origine psychique et/ou cognitive de l’adulte, s’appuie sur le fait que les limitations d’activité et restrictions de la participation consécutives à des déficits du fonctionnement cognitif, et/ou du fonctionnement psychique créent des situations de handicap. On l’observe dans de nombreuses pathologies: retards mentaux, psychoses chroniques, affections cérébrales (de type accidents vasculaires cérébraux, traumatismes crâniens), affections cérébro-dégénératives, démences et maladie d’Alzheimer. Malgré les progrès de la prise en charge médicale et des traitements de ces affections, le handicap d’origine psychique ou cognitive représente un problème prioritaire de santé publique, du fait de son importance quantitative, de l’intensité de la souffrance des personnes concernées et de leur entourage, et de son coût social considérable lié à la nécessité d’institutionnalisations de long séjour (au moins en France) ainsi que d’aides humaines pour l’autonomie personnelle et sociale de ces personnes. Deux pathologies très différentes sur le plan étiopathogénique et l’expression clinique, le traumatisme crânio-cérébral et la schizophrénie, sont toutes deux responsables d’un handicap psychique et/ou cognitif à la fois fréquent et sévère. Par exemple, on sait que moins de la moitié des traumatisés crâniens graves retrouvent une autonomie pour les actes complexes de la vie citoyenne et sociale et 12 % seront définitivement institutionnalisés . La vie familiale, la sexualité , la reprise ou l’acquisition d’un travail , l’accès aux loisirs et globalement le fait de vivre autonome et productif dans la société sont très perturbés par les conséquences d’un traumatisme crânien. De même, la schizophrénie qui représente la 8 e cause d’incapacité chez les 15–44 ans , devant plusieurs affections médicales majeures, comme le cancer ou l’asthme, perturbe gravement l’insertion dans la communauté. En Europe, 80 % des individus souffrant de schizophrénie sont sans emploi, et 17 % seulement sont mariés , avec peu de variation d’un pays à l’autre . Les individus souffrant de troubles schizophréniques signalent une réduction significative de leur qualité de vie en termes de loisirs, relations sociales, famille et travail par rapport aux sujets exempts de pathologie mentale .

Or, l’identification des difficultés d’insertion sociale a toujours été plus difficile pour les personnes en situation de handicap pour raison psychique et/ou cognitive, que pour les personnes présentant des déficiences physiques. Le terme de handicap invisible porte bien son nom ! Les obstacles à l’insertion sont plus souvent liés aux attitudes, aux préjugés d’un commerçant ou d’un employeur, au regard porté par notre société en général et quelquefois aussi dans les orientations des politiques publiques qu’aux barrières architecturales . L’évaluation de ces situations pour des raisons administratives ou médicosociales (grille AGGIR, observatoires régionaux de santé, détermination des besoins en aides humaines par la procédure GEVA des MDPH, expertises médicolégales) reste difficile et controversée. Les troubles cognitifs, les troubles psychiques, les troubles du comportement ne sont pas évalués spécifiquement. La particularité de ces difficultés vis-à-vis de l’affection en cause et l’influence des facteurs d’environnement restent également mal connues : les données de la littérature ne permettent pas actuellement de dire si des affections différentes sont reliées de manière équivalente aux mêmes restrictions de participation.

En renouvelant radicalement les modèles théoriques du handicap, notamment par la prise en compte d’une part, du degré d’implication réelle dans les situations de la vie (participation), et d’autre part, des facteurs contextuels et d’environnement, la classification internationale du fonctionnement (CIF) représente un cadre pertinent pour aider à clarifier cette question.

Il n’est pas inutile de rappeler les changements majeurs apportés par la CIF. La question du handicap y est abordée sous les deux composantes de fonctionnement de la personne et des facteurs contextuels. Le fonctionnement de la personne est conçu à travers la composante organique (structure et fonctions) et la composante activité et participation. Cette séparation arbitraire permet cependant de se focaliser plus facilement sur l’activité (les tâches que peut faire une personne) et son corollaire (les limitations d’activité qui sont les difficultés que rencontre une personne dans l’exécution de certaines activités ou tâches). Concernant la participation (l’implication d’une personne dans une situation de la vie réelle), la CIF favorise l’appréhension de la notion d’implication (les restrictions de participation désignent les problèmes qu’une personne peut rencontrer en s’impliquant dans une situation de la vie réelle). Nous avons déjà abordé en le simplifiant que l’activité correspond à la capacité qu’a une personne de réaliser une tâche (pouvoir faire, notion de compétence). La participation, quant à elle, est plutôt la mesure de l’engagement de la personne, son implication à être dans l’activité et à réaliser effectivement la tâche (le faire vraiment, notion de performance). Le résultat est à relier avec les composantes environnementales (physique et relationnelles) et les facteurs personnels (liés à l’histoire de la personne, ses habitudes de vie, ses goûts…). Bien sûr la CIF est une classification et, à ce titre, a pour vocation de décrire le fonctionnement humain dans ses moindres détails. Les caractéristiques du fonctionnement humain étant sujettes à une très grande variabilité, c’est le concept adapté à une personne en particulier qui nous a semblé le plus pertinent dans cette approche du fonctionnement.

La CIF dans cette recherche permet de prendre en compte d’une part les limitations d’activité signalées par le sujet, l’estimation de son degré d’implication réelle dans les situations de la vie (restrictions de la participation), et d’autre part, les facteurs environnementaux (physiques, du domicile à la cité par exemple) et contextuels (cadre relationnel, emploi, vie citoyenne). Un des objectifs de cette recherche est de créer un document d’évaluation situationnelle dérivé de la CIF. Il s’agit d’apporter des informations sur les critères métrologiques et l’intérêt d’une grille standardisée et enfin d’étudier les limitations d’activités vs les restrictions de participation. Cette étude concerne les populations souffrant de troubles schizophréniques ou traumatisme crânien, présentant un handicap psychique et/ou cognitif.

Dans cet article, un exemple issu de l’entretien avec Mr F ( Annexe 3 ) permettra au lecteur de se familiariser avec les notions centrales de limitation d’activité, de restriction de participation et de facteurs environnementaux.

2.1

Matériel et méthodes

2.1.1

Développement de l’outil

Un premier repérage des difficultés d’insertion des patients en situation de handicap après traumatisme crânien ou troubles schizophréniques a été effectué à partir d’une analyse de la littérature, de l’expérience de cliniciens et des chercheurs de l’équipe représentant diverses approches professionnelles : médecine physique et réadaptation (MPR), psychiatrie, ergothérapie, psychologie et neuropsychologie.

La deuxième étape a consisté à mieux définir le contenu et limites des concepts de handicap d’origine psychique et/ou cognitive. Pour cela, nous avons exploité le résultat d’une première étude (non publiée) effectuée en 2007 avec le centre collaborateur OMS pour la CIF en langue française (anciennement CTNERHI) et un institut de formation en ergothérapie. Nous avions utilisé l’ICF Checklist de l’OMS dans différentes structures de la région (centre de rééducations, centre d’hébergement, familles d’accueil, centre hospitalier spécialisé, SAMSAH [service d’accompagnement médicosocial pour adultes handicapés]) mais aussi interrogé directement à leur domicile des usagers souffrant des conséquences de lésions cérébrales ou de troubles psychiques. Nous en avions retenu une collection de récits de situations concrètes de limitations d’activité et de restriction de la participation subies par ces personnes. Sous la supervision de l’un des auteurs (CB) et d’une sociologue (CB) responsable du centre collaborateur OMS pour la CIF en langue française, nous avons rapproché cet ensemble de données, des situations d’activité auxquelles se réfère la CIF. Il est très vite devenu évident que l’évaluation du rôle des facteurs personnels et d’environnement allait être à la fois difficile et déterminante pour l’efficacité de l’outil. Nous avons inclus cette réflexion concernant les facteurs personnels et facteurs contextuels, pour sélectionner les catégories de la CIF sur lesquelles devrait se baser l’outil.

La troisième étape a consisté à présenter et confronter les catégories de la CIF ainsi retenues, à l’expérience des consultants représentant l’Union nationale des amis et familles de malades psychiques (UNAFAM) et l’Union nationale des associations de familles de traumatisés crâniens (UNAFTC). Les discussions souvent très argumentées et passionnées qui ont suivi chaque présentation d’une catégorie de la CIF ont permis de sélectionner et de classer de manière consensuelle les situations de vie quotidienne retenues (toujours en référence aux rubriques de la CIF).

Au cours de cette troisième étape, et afin de mieux s’accorder sur les critères à développer dans les facteurs environnementaux et facteurs personnels, un sous-groupe dirigé par l’un des auteurs (MK), chercheur en psychologie de la santé, spécialisée dans l’évaluation des processus d’ajustement et de soutien social, a travaillé cet aspect particulier et proposé des variables spécifiques comme le type d’aide humaine reçue, la qualité de la personne qui donne de l’aide et la satisfaction que le sujet en retire telle qu’il peut l’évaluer. L’accent a été mis sur la notion de soutien social perçu qui correspond au sentiment qu’éprouve une personne sur la possibilité qu’elle a, ou non, d’être aidée, protégée et valorisée par son entourage.

Dans les facteurs environnementaux, on considère le soutien social perçu dans son aspect quantitatif et qualitatif. L’aspect quantitatif correspond à la disponibilité du soutien social (SSD) : c’est le nombre de personnes qui sont prêtes, selon l’individu, à l’aider dans les moments difficiles (ou pas), celles sur lesquelles il estime pouvoir compter. L’aspect qualitatif porte sur la satisfaction liée au soutien social (SSS). Il s’agit de la satisfaction qu’éprouve la personne par rapport au soutien qu’elle estime avoir obtenu : un soutien social n’est satisfaisant que si la personne évalue ce qu’elle reçoit (ou pense recevoir) comme étant adéquat par rapport à ses attentes et besoins. Elle peut aussi ne pas recevoir d’aide et en être satisfaite !

La cotation de la disponibilité du soutien social (SSD) tient compte du nombre de catégories de personnes susceptibles d’apporter du soutien ou une aide concrète (de 0 à 3 catégories, par exemple, la famille, les amis, des connaissances, les professionnels…), et cela dans chacune des situations proposées.

La cotation de la satisfaction du soutien social (SSS) qu’en retire la personne se fait par une échelle en 5 points : insatisfait, plutôt insatisfait, moyennement satisfait, plutôt satisfait, satisfait.

Toujours dans les facteurs d’environnement, le rôle des attitudes envers la personne interrogée et celui des systèmes et politiques publiques est classé en obstacle, facilitateur, les deux (mixte) ou indifférent.

L’ensemble a abouti à l’élaboration d’une grille-prototype de 26 items qui a été testée chez 10 sujets. Ce premier test a conduit à la reformulation de plusieurs questions du guide d’entretien et du système de cotation. La grille finale : G-MAP (Grille de Mesure de l’Activité et de la Participation [ Annexe 1 ]) comporte 26 items, avec pour chacun d’eux, une cotation ordinale de l’activité et de la participation. Elle est remplie à l’issue d’un entretien semi-dirigé construit autour de questions repères dont quelques exemples sont présentés dans l’ Annexe 2 .

Tous les entretiens ont été filmés par un interviewer/évaluateur unique (certains entretiens ont duré plus de quatre heures [avec coupures !]). La cotation a été faite par deux évaluateurs différents à des temps différents (l’interviewer/évaluateur et un deuxième évaluateur à partir du film enregistré).

À la fin de chaque entretien, nous avons recueilli l’appréciation générale que les sujets pouvaient nous restituer de l’évaluation G-MAP.

2.1.2

Variables psychologiques et comportementales

Afin de situer les échantillons par rapport à la population générale et/ou la littérature internationale, des évaluations psychométriques du fonctionnement cognitif, du soutien social et de l’estime de soi ont également été réalisées :

- •

fonctionnement cognitif : vitesse de traitement : Codes de la WAIS-III , mémoire de travail : mémoire des chiffres de la WAIS-III, mémoire épisodique : RL/RI 16 , fonctionnement exécutif : Stroop test , cognition sociale : Test d’attributions d’intention ;

- •

fonctionnement psychologique : estime de soi : Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale, , soutien social perçu évalué en termes de disponibilité et de satisfaction : Social Support Questionnaire-6 ;

- •

évaluations spécifiques au groupe troubles schizophréniques : Échelle Globale de Fonctionnement EGF , Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale PANSS ;

- •

évaluation spécifique au groupe traumatisme crânien : Échelle Neurocomportementale Révisée NRS-R .

2.1.3

Participants

L’évaluation a concerné 16 sujets traumatisés crâniens à distance du traumatisme de 5 à 220 mois (soit une moyenne de 87 mois [environ 7 années]) et 15 patients présentant des troubles schizophréniques chroniques cliniquement stabilisés (nous avons pris en compte le diagnostic posé à l’occasion d’une consultation ou d’une hospitalisation) de 4 à 230 mois (soit une moyenne de 110 mois [environ 9 années]).

Les sujets victimes d’un traumatisme crânien ont été sollicités de façon consécutive à la consultation d’un service hospitalo-universitaire de médecine physique et réadaptation, et à l’unité d’évaluation et ré-entraînement et d’orientation socio-professionnelle (UEROS) associée à ce CHU. Les critères d’inclusion étaient les suivants : être âgé de 16 à 65 ans, parler le français couramment, avoir subi un traumatisme crânien fermé ou ouvert de gravité définie par le score initial à l’Échelle de Glasgow, avoir signé un formulaire de consentement éclairé. Les sujets présentant une déficience motrice et/ou sensorielle associée importante, ou des antécédents de troubles psychiatriques ont été exclus.

Les sujets souffrant de troubles schizophréniques ou de troubles schizo-affectifs selon les critères du DSM-IV-TR ont été contactés individuellement dans un centre hospitalier spécialisé selon les critères d’inclusion suivants : être âgé de 16 à 65 ans, parler le français couramment, être à distance d’une crise psychotique aiguë, de la période de stabilisation des symptômes et du traitement pharmacologique (au moins un mois), avoir signé un formulaire de consentement éclairé. Le consentement est obtenu par la signature du formulaire après avoir expliqué le but de la recherche, et ses moyens (entretien semi directif portant sur les éventuelles difficultés rencontrées dans la vie quotidienne) et ses modalités (entretien enregistré), ainsi que la qualité professionnelle des personnes en charge de l’étude. Une seule personne a refusé l’entretien.

Les patients suivant un protocole de traitement par électro-convulsivothérapie ou stimulation magnétique transcrânienne, ou présentant un épisode dépressif majeur, une dépendance à l’alcool ou à une autre substance psychoactive selon les critères du DSM-IV-TR, ou des antécédents neurologiques tels qu’un traumatisme cranio-cérébral ont été exclus. Cinq patients étaient hospitalisés, et 10 en suivi ambulatoire à la date de l’étude.

2.1.4

Traitement statistique des données

La consistance interne des limitations d’activité et des restrictions de participation de la G-MAP a été évaluée par le coefficient α de Cronbach. La comparaison des deux groupes sur les scores aux différents tests cognitifs et psychologiques et sur les scores de limitations d’activité et de restrictions de participation évalués par la G-MAP a été réalisée à l’aide du test de Mann-Whitney (U). Les résultats ont été considérés comme significatifs quand p < 0,05.

2.2

Résultats

Le Tableau 1 présente les caractéristiques cliniques des patients et les résultats des tests cognitifs et psychologiques. Les sujets sont surtout des hommes, célibataires. La moyenne d’âge est plus élevée dans le groupe de patients souffrant de troubles schizophréniques, mais de façon non significative. Par rapport aux normes francophones récentes , les tests cognitifs montrent des performances moyennes normales ou légèrement abaissées dans la plupart des fonctions mesurées. On peut cependant souligner la faiblesse du score standard au Code de la WAIS III (−1,7 ET), qui suggère un ralentissement cognitif significatif. L’estime de soi se situe dans la norme. Globalement, les résultats sont très comparables entre les 2 groupes, à l’exception d’un temps moyen plus long au test de Stroop, d’un soutien social jugé moins disponible et moins satisfaisant et d’une estime de soi légèrement inférieure chez les patients souffrant de troubles schizophréniques. Ces différences ne sont cependant pas significatives.

| TS | TC | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | 15 | 16 | |

| Âge | 42,8 (11,9) | 31,6 (10,2) | 0,28 |

| Sexe (hommes/femmes) | 8/7 | 14/2 | 0,06 |

| Niveau éducation | |||

| Primaire | 3 | 4 | |

| CAP-BEP | 7 | 4 | |

| Bac et + | 5 | 8 | |

| En couple | 2 | 4 | |

| TP mémoire des chiffres | 7 (2,6) | 7 (3,2) | 0,48 |

| TP code | 4,3 (1,9) | 5,2 (2,7) | 0,36 |

| TP RL/RI 16 | |||

| Rappel libre | 10,6 (2,1) | 11,1 (1,8) | 0,33 |

| Total | 15,6 (0,9) | 15,7 (0,6) | 0,08 |

| TP Stroop | 89,4 (57) | 62,3 (38,5) | 0,06 |

| TP attribution d’intention | 45,5 (10,4) | 52,1 (8,5) | 0,14 |

| TP estime de soi | 28,2 (7) | 32,5 (5,2) | 0,14 |

| TP soutien social perçu | |||

| Disponibilité | 11 (8) | 18,2 (10,7) | 0,07 |

| Satisfaction | 22 (10,1) | 30,5 (7,1) | 0,10 |

| TDTS EGF | 45,6 (18,7) | ||

| TDTS PANSS | |||

| Échelle positive | 25,1 (7,6) | ||

| Échelle négative | 31,5 (6,8) | ||

| Score général | 58,5 (12,1) | ||

| TDTC NRS-R | 11 (5,2) | ||

À la G-MAP, la consistance interne des limitations d’activité et des restrictions de participation, évaluée sur la totalité des items, est satisfaisante avec des valeurs du coefficient α de Cronbach de 0,89 pour chacune de ces deux dimensions. Pour les limitations d’activité, les items de chacune des 6 catégories (pour le détail des rubriques abordées, voir l’exemplaire de la grille d’entretien) sont globalement à peu près homogènes : les coefficients α de Cronbach vont de 0,40 (catégorie vie communautaire) à 0,80 (catégorie productivité). Pour les restrictions de participation, la consistance interne des différentes catégories est plus faible : α de Cronbach de 0,17 (catégorie vie communautaire) à 0,77 (catégorie soins personnels).

Le Tableau 2 présente les scores moyens de limitations d’activité et de restrictions de participation pour chacun des 26 items de la G-MAP. Les restrictions de participation sont sévères vis-à-vis de la gestion du budget, la vie de couple, les relations sexuelles, les études, le travail ou les activités bénévoles, et tous les items de vie communautaire : participation au milieu associatif, gestion administrative, vie citoyenne et vote, spiritualité. Elles sont présentes mais moins sévères vis-à-vis des relations avec les parents, la fratrie, les amis et les connaissances, et vis-à-vis des loisirs. Les catégories soins personnels et vie domestique sont moins concernées.

| Catégorie CIF | Items | LA TS | LA TC | LA Total | RP TS | RP TC | RP Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soins personnels | Hygiène | 0,00 | 0,63 | 0,32 | 0,33 | 0,19 | 0,26 |

| Alimentation | 0,13 | 0,19 | 0,16 | 0,53 | 0,19 | 0,35 | |

| Prendre soin de sa santé | 0,53 | 0,25 | 0,39 | 0,47 | 0,31 | 0,39 | |

| Vie domestique | Vêtements, linge | 0,13 | 0,13 | 0,13 | 0,47 | 0,19 | 0,32 |

| Entretien, ménage | 0,47 | 0,13 | 0,29 | 0,67 | 0,19 | 0,42 | |

| Déplacements extérieurs | 0,73 | 0,19 | 0,45 | 0,73 | 0,31 | 0,52 | |

| Gestion du budget | 0,80 | 0,50 | 0,64 | 1,00 | 0,63 | 0,81 | |

| Achat, courses | 0,47 | 0,13 | 0,29 | 0,60 | 0,50 | 0,55 | |

| Relations interpersonnelles | Parents, fratrie, enfants | 0,40 | 0,25 | 0,32 | 0,64 | 0,44 | 0,53 |

| Couple (si approprié) | 1,07 | 0,31 | 0,68 | 1,87 | 1,47 | 1,67 | |

| Relations sexuelles | 0,73 | 0,06 | 0,39 | 1,67 | 1,00 | 1,32 | |

| Amis | 0,53 | 0,00 | 0,26 | 1,20 | 0,25 | 0,71 | |

| Connaissances | 0,33 | 0,19 | 0,26 | 0,87 | 0,56 | 0,71 | |

| Inconnus | 0,53 | 0,19 | 0,35 | 1,00 | 0,56 | 0,77 | |

| Productivité économique et sociale | École, formation, études | 1,43 | 0,63 | 1,00 | 2,00 | 1,81 | 1,90 |

| Recherche de travail/formation | 1,29 | 0,44 | 0,83 | 1,50 | 0,75 | 1,10 | |

| Travail | 1,20 | 0,50 | 0,84 | 1,73 | 1,44 | 1,58 | |

| Bénévolat | 0,80 | 0,25 | 0,52 | 1,67 | 1,19 | 1,42 | |

| Indépendance financière | 0,73 | 0,56 | 0,65 | 1,07 | 1,31 | 1,19 | |

| Loisirs | D’intérieur (TV, cartes) | 0,13 | 0,06 | 0,10 | 0,87 | 0,50 | 0,68 |

| D’extérieur (sports, promenade) | 0,47 | 0,06 | 0,26 | 1,13 | 0,50 | 0,81 | |

| De groupe (restaurants, pétanque) | 0,73 | 0,31 | 0,52 | 1,27 | 0,94 | 1,10 | |

| Vie communautaire et civique | Vie associative | 1,07 | 0,38 | 0,71 | 1,80 | 1,81 | 1,81 |

| Spiritualité | 1,20 | 1,19 | 1,19 | 1,27 | 1,50 | 1,39 | |

| Démarches administratives | 0,93 | 0,50 | 0,71 | 1,13 | 0,69 | 0,90 | |

| Vote | 0,27 | 0,00 | 0,13 | 1,40 | 0,81 | 1,10 | |

Le Tableau 3 présente les scores moyens et écarts-types obtenus aux limitations d’activité et restrictions de participation pour les 6 catégories de la G-MAP. En ce qui concerne les limitations d’activité, on observe qu’elles sont surtout présentes pour productivité, notamment l’indépendance financière, et vie communautaire, notamment la vie spirituelle, et qu’elles sont au contraire minimales pour soins personnels. Les catégories vie domestique, relations et loisirs sont en position intermédiaire. Les limitations d’activité sont plus marquées chez les personnes souffrant de troubles schizophréniques que chez les traumatisés crâniens pour les catégories relations interpersonnelles ( p = 0,006) et productivité ( p = 0,011). Pour soins personnels, loisirs et vie communautaire, les scores moyens sont proches (U de Mann-Withney non significatifs). De la même façon, les restrictions de participation sont plus importantes chez les personnes souffrant de troubles schizophréniques que chez les traumatisés crâniens pour les catégories relations interpersonnelles ( p = 0,005), productivité ( p = 0,012) et vie domestique ( p = 0,045). Les deux groupes sont donc différents dans la sévérité des restrictions qui apparaissent systématiquement plus marquées chez les personnes souffrant de troubles schizophréniques. Cependant, il est intéressant de noter que l’ordre d’importance des catégories de restrictions de participation est exactement le même dans les deux groupes.

| Soins personnels | Vie domestique | Relations interpersonnelles | Productivité économique et sociale | Loisirs | Vie communautaire et civique | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Limitations d’activité | ||||||

| TS | 0,22 (0,30) | 0,52 (0,51) | 0,60 (0,48)* | 1,11 (0,64)* | 0,44 (0,54) | 0,63 (0,45) |

| TC | 0,17 (0,42) | 0,21 (0,31) | 0,17 (0,17)* | 0,48 (0,53)* | 0,15 (0,24) | 0,39 (0,33) |

| p | 0,233 | 0,079 | 0,006 | 0,011 | 0,106 | 0,116 |

| Restrictions de participation | ||||||

| TS | 0,51 (0,49) | 0,69 (0,46)* | 1,21 (0,35)* | 1,64 (0,27)* | 1,09 (0,68) | 1,40 (0,32) |

| TC | 0,23 (0,54) | 0,36 (0,34)* | 0,70 (0,47)* | 1,30 (0,38)* | 0,65 (0,58) | 1,20 (0,43) |

| p | 0,052 | 0,045 | 0,005 | 0,012 | 0,062 | 0,202 |

En ce qui concerne les facteurs environnementaux, les trois facteurs : soutien social, attitudes, systèmes et politiques ont été analysés de manière descriptive pour chacun des 26 items. La distribution des scores apparaît très variable en fonction des items et des sujets, ce qui montre la pertinence de la grille pour une évaluation personnalisée détaillée. La distribution est, le plus souvent, différente entre les groupes, ce qui suggère que l’effet des facteurs d’environnement varie selon le type d’étiologie. Une analyse exhaustive serait fastidieuse étant donné le nombre de facteurs : 4, multiplié par le nombre d’items : 26. La Fig. 1 en donne quelques exemples ( Fig. 1 ). Quand on observe le facteur « disponibilité du soutien social » évalué par la G-MAP, on remarque qu’un plus grand nombre de catégories de soutien social est cité par les personnes souffrant de troubles schizophréniques que par les personnes victimes de traumatisme crânien. Par contre, ces derniers citent majoritairement la catégorie « professionnels » (par exemple, Fig. 1A ), celle-ci étant vécue comme la catégorie dominante. Pour le facteur « satisfaction du soutien social », tous les types de réponse de « insatisfait » à « satisfait » s’observent dans les deux groupes, sans prédominance particulière . Le facteur « attitudes » joue un rôle globalement modéré, jugé deux fois plus souvent facilitateur qu’obstacle, mais avec de grosses variations d’un sujet à l’autre, par exemple pour l’item attitudes des « parents, fratrie, enfants » ( Fig. 1B ). Pour l’item « recherche de travail ou formation », les attitudes jouent très majoritairement un rôle d’obstacle pour les personnes ayant subi un traumatisme crânien ( Fig. 1C ). Quand les personnes souffrant de troubles schizophréniques sont concernées, elles peuvent en revanche être indifférentes aux attitudes, ce qui n’est pas le cas des traumatisés crâniens. Pour cet item, il est intéressant de souligner que la réponse « rôle facilitateur » n’a jamais été donnée. Le facteur « systèmes et politiques publiques » joue un rôle nettement plus important, tantôt jugé facilitateur (vie domestique), tantôt obstacle (relations interpersonnelles, productivité), tantôt les deux (loisirs). L’effet facilitateur dans le domaine des « démarches administratives » est mentionné par les personnes souffrant de troubles schizophréniques, mais pas par les traumatisés crâniens ( Fig. 1D ). On observe la même différence pour l’item « indépendance financière ».