Parkinson’s disease

Michael L. Moran

Introduction

Parkinson’s disease (PD), also known as paralysis agitans, is a progressive neurodegenerative disease that affects approximately 1% of those over the age of 60 years. With the aging of the population, this number is expected to increase. For example, PD affects approximately one million people in the United States of America. Globally, the number of individuals with PD was estimated at 4 million in 2005, and is expected to reach 9 million by 2030 (Georgy et al., 2012). Men and women are equally affected.

PD results from a loss of pigmented neurons in the substantia nigra which leads to a reduction in the production of the neurotransmitter dopamine. The resulting movement disorders are characterized by tremor, rigidity, bradykinesia and postural instability. Diagnosis is usually made by observation of signs and symptoms and may be facilitated by positron emission tomography (PET) scans as well as single photon emission computer tomography (SPECT) (Winogrodzka et al., 2005). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computerized tomography (CT) can be useful in differentiating PD from other disorders. A clinical presentation that mimics but is different from PD is called Parkinson’s syndrome or parkinsonism.

Parkinsonism is a frequent cause of functional impairment in the elderly. The diagnosis is based on an evaluation of four signs: resting tremor, akinesia, rigidity and postural abnormalities. Parkinsonism may be caused by PD and can be a part of the clinical presentation of other neurodegenerative diseases (Bhalsing et al., 2013).

Signs and symptoms

The signs and symptoms of PD vary, depending on the stage of the disease. The early stage may include tremor (often unilateral) and a sense of fatigue. The middle stage usually includes tremors, varying degrees of rigidity, bradykinesia, postural changes, instability and the patient may begin to require assistance from caregivers. The final stage of PD includes extensive motor disorders, requiring that the patient be assisted in performing activities of daily living (ADLs) and moving. Cognitive changes (depression, dementia) commonly accompany PD (Johnson & Galvin, 2011).

Tremors are present at rest and usually disappear as a patient attempts to move and during sleep. The term given to the commonly observed repetitive finger movements is ‘pill-rolling’. Clinically, it has been observed that PD patients move slowly, and with inconsistent acceleration, and this bradykinesia is often noticeable when the patient progresses from the early stages of the disease. A complete lack of movement (akinesia) may occur. PD patients can ‘freeze’ in a certain position (including standing) and then spontaneously begin to move again. Rigidity has been linked to the development of contractures, fixed kyphosis and loss of pelvic mobility. Postural instability most likely reflects central nervous system pathology as well as the musculoskeletal changes mentioned above.

Interventions

The management of PD usually combines nonpharmacological and pharmacological treatments. The former should include a multidisciplinary approach involving various therapies (physical, occupational and speech) emphasizing the patient’s independence and training of the caregiver. Musculoskeletal changes associated with aging should not be confused with the changes typically seen in PD: a forward-thrust head, increased thoracic kyphosis, posterior pelvic tilt and a slow, shuffling gait. Instead, a PD patient should be objectively evaluated using an appropriate device such as the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (Goetz et al., 2008; Table 30.1). The clinical assessment can be video recorded, which allows changes in movement disorders to be more easily tracked. Also, research has shown that various tools, such as the Timed Up and Go Test and the Dynamic Gait Index, have acceptable measurement error and test–retest reliability. Tools such as these can help clinicians determine whether a change in a patient with PD is a true change (Huang et al., 2011).

Table 30.1

Unified Parkinson’s disease rating scale (modified Hoehn and Yahr staging)

| Stage 0 | No signs of disease |

| Stage 1 | Unilateral disease |

| Stage 1.5 | Unilateral plus axial involvement |

| Stage 2 | Bilateral disease, without impairment of balance |

| Stage 2.5 | Mild bilateral disease, with recovery on pull test |

| Stage 3 | Mild to moderate bilateral disease; some postural instability; physically independent |

| Stage 4 | Severe disability; still able to walk or stand unassisted |

| Stage 5 | Wheelchair bound or bedridden unless aided |

Source: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK27684.

Nonpharmacological management

Therapeutic intervention should begin as early in the disease state as possible. Avoiding soft tissue contracture, loss of joint range of motion, reduction in vital capacity, depression and dependence on others enhances the quality of life of the PD patient. It is important to include caregivers and others significant to the patient in goal- setting and planning interventions.

Intervention should be goal-oriented (i.e. preventing loss of function is the desired outcome) and individually tailored, based on the stage the patient is in. Relaxation exercises may be useful to reduce rigidity and there is some support for the idea that strengthening exercises may help to prevent falling. However, patient adherence to exercise programs is an important issue (Pickering et al., 2013). Stretching and active range of motion (ROM) exercises are vital, and the patient should be provided with a home program to facilitate improvement in functional postural alignment. Breathing and endurance exercises can help to maintain vital and aerobic capacities. They are important, as PD patients have a high incidence of pulmonary complications such as pneumonia. Balance, transfer and gait activities (including weight shifting) are also recommended.

Balance training should include repetitive training of compensatory steps (Jobges et al., 2004), and practice at varied speeds as well as self-induced and external displacements. Self-induced displacements are necessary to help the patient in tasks such as leaning, reaching and dressing. Displacements of an external origin may be expected if a patient is walking in crowds or attempting to negotiate uneven or unfamiliar terrain. External displacements may be simulated by the use of gradual resistance via rhythmic stabilization. Neurofeedback (Rossi-Izquierdo et al., 2013) and tai chi (Tsang, 2013) have been shown to improve balance in patients with PD.

Transfer training should focus on those activities reasonably expected of the patient. At a minimum, bed mobility and transfers, and chair and commode transfers should be considered. Limitations in active trunk and pelvic rotation may impair a PD patient’s mobility in bed. Satin sheets or a bed cradle may reduce resistance to movement from friction. An electric mattress warmer may ease mobility by reducing the need for and thus the weight of covers. If the PD patient cannot be taught to perform a transfer independently, accommodations should he considered. Examples include bed rails or a trapeze, a lift chair and a commode with arms.

Specific training may enhance a PD patient’s ability to perform some transfers such as sit to stand. Evidence indicates that strategies designed to facilitate tibialis anterior activation may improve sit to stand performance (Bishop et al., 2005). Mak and Hui-Chan (2008) reported that cued task-specific training was better than exercise in improving sit to stand in patients with PD. More recently, Mak et al. (2011) noted that limb support and ill-timed peak forward center of mass velocity, rather than dynamic stability, play dominant roles in determining successful sit to stand performance in patients with PD.

Gait training should focus on musculoskeletal limitations that can be quantified. PD patients tend to have limitations in ankle dorsiflexion, knee flexion/extension, stride length, hip extension and hip rotations. Joint mobilization and soft-tissue stretching can be effective to increase ROM and improve gait. It is important to include trunk mobility (rotation) and upper extremity ROM (large, reciprocal arm swings) in a comprehensive gait training program for PD patients. Ebersbach et al. (2010) reported that high amplitude movements were an effective technique to improve motor performance in patients with PD.

Rhythm or music may facilitate movement, but the use of assistive devices such as canes and walkers is not always appropriate for PD patients. At times, the use of an assistive device increases a festinating gait or aggravates problems with balance or coordination. Care should be taken to avoid excessive musculoskeletal stress and falls. Conditions such as osteoporosis may predispose a patient to injury.

For PD patients, a primary problem is difficulty in motor planning. Complex tasks such as transferring out of bed and walking to the bathroom have to be broken down into simple components (Bakker et al., 2004). It is important for patients and caregivers to remember that verbal and physical cuing (and other forms of assistance) should be oriented toward completion of a number of simple tasks in order to accomplish the overall goals of maintaining function and mobility. It has been noted that stress, fatigue, anxiety, or need to hurry imposed by the caregiver may exacerbate the freezing associated with PD. Further, Schenkman et al. (2011) stated that functional loss occurs at different points in the disease process, depending on the task under consideration.

When examining and planning interventions for a PD patient, common age-related changes must be considered. For instance, older individuals are more sensitive to glare and benefit from contrasting colors when determining depth. These facts are especially evident when working in some environments during activities such as gait training on steps. Further, some signs and symptoms of PD have been confused with changes associated with aging. PD patients may present with a reduced or lost sense of smell, handwriting that is difficult or impossible to read, and changes in sleep patterns.

Specific nonpharmacological interventions include biofeedback, proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation, Feldenkrais and the Alexander Technique (Stallibrass, 2002). In addition, treadmill training, spinal flexibility training, Qigong and tango dancing appear to be of some benefit for people with PD (Morris et al., 2010). Technology can also play a role in helping patients with PD: Ledger et al. (2008) reported that auditory cueing devices can improve walking speed, stride length and freezing.

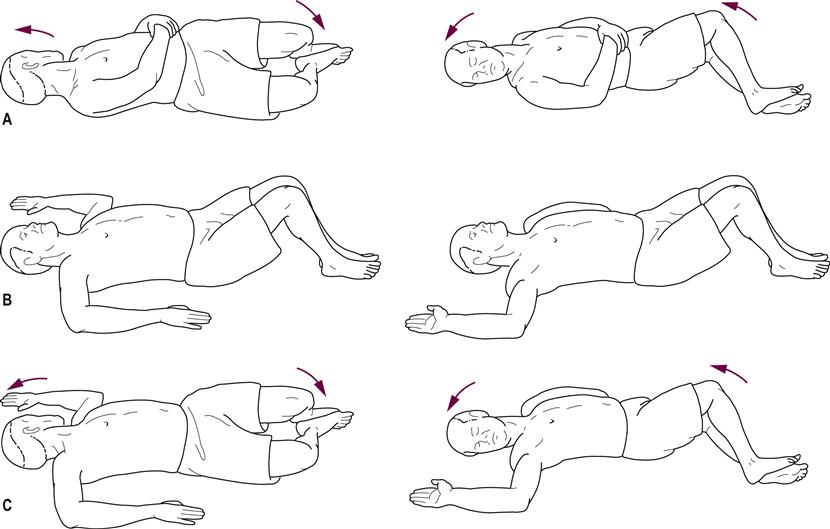

Stretching, active ROM and strengthening exercises should emphasize safety: patients should be placed in a fully supported position initially and progressed to unsupported positions. In addition, spinal mobility must be oriented toward complete full normal rotation, including elongation of trunk musculature. A loss of pelvic motion occurs and can be addressed by means of lateral and anterior/posterior tilts; for instance, the functional task of standing from a seated position can incorporate anterior pelvic tilts. Mobility in bed, such as rolling over, can include trunk rotation. To improve postural (i.e. balance) responses, a variety of balance activities has been recommended (Hirsch et al., 2003). It is noted, however, that a variety of tasks should be practiced, as skills tend to be task-specific (de Lima-Pardini et al., 2012). Examples of some of the mobility skills are shown in Figures 30.1, 30.2 and 30.3.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree