5 Palpation

• Examining and assessing tissues;

• Recognising the end-feel of the tissue, which influences the effectiveness and comfort of the massage;

• Modifying techniques to different tissues and tissue layers;

• Adapting techniques to suit an individual’s tissues; and

• Adapting techniques so that they are appropriate to various pathological states and stages of healing.

Exercises to develop palpation skills

• Take two small bowls and put refined white flour into one and wholewheat flour into the other. Simultaneously put one hand into each and rub the flour between your fingers. Describe to yourself the different sensations.

• Collect together a number of different grades of sandpaper. Close your eyes and attempt to sort the paper by grade.

• Compare the differences in the texture of water, cooking oil and a thick body lotion by rubbing a little of each between finger and thumb.

• Place some small objects on a table (e.g. grains of rice, a piece of string, a matchstick, a key, a paperclip). Cover them with a thin cloth and palpate; repeat with thicker coverings such as a blanket and a piece of foam. Distinguish the variation of sensations between the covers and note any differences in the pressure you have applied.

• With one finger stroke your cheek, your arm, your palm, your abdomen, your knee and the sole of your foot. Feel any varying texture, skin temperature and moisture in these parts of the body.

• Practise palpation in the area of your wrist and forearm. The anterior aspect of the wrist is a good place to start; here you can see and feel the tendons and blood vessels. Let the fingers of one hand rest as lightly as a feather on your contralateral wrist. Move them very gently over the skin without stretching and register what you feel. Now apply slightly more pressure, so that the skin moves with your fingers; this should give you more information about the structures under the skin. Apply more pressure still so that the subcutaneous structures are compressed on the underlying bone. With this heavy pressure the sensitivity of your palpation decreases and the structures will not be so easy to differentiate.

• Palpate your own thigh. Note the depth of pressure required to gain information about the tone of the muscles in this region. Using your whole hand pick up and stretch the muscles and register any changes you feel in the resistance of the tissues.

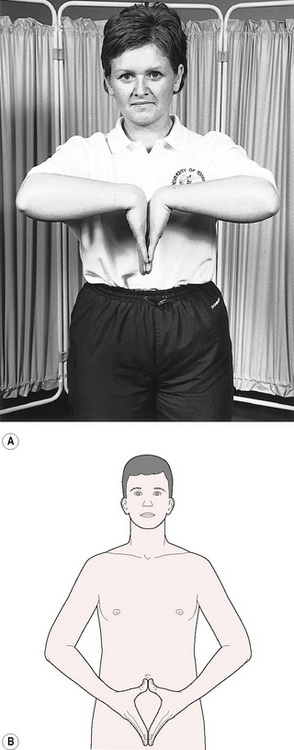

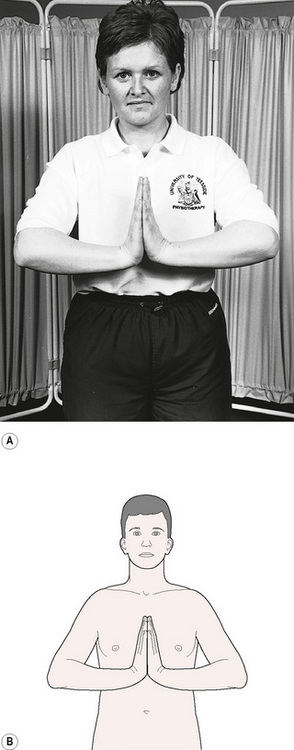

It is useful to perform specific exercises to increase the mobility of your hands before you begin to learn massage. Figures 5.1 and 5.2 show suggested exercises for stretching your fingers and wrists.