Chapter 13 Pain Management

Acute pain relief

Drug therapy

Therapeutically effective analgesia should also be given in the form that is most likely to ensure maximum placebo effect. Analgesia must satisfy the brain’s desire for an adequate treatment that will allow it to reduce the synaptic strength and connectivity within the CNS supporting the pain state (Wall 1999, Roche 2002).

• Prescribing, giving and timing of adequate analgesia facilitates effective physical treatment. Analgesia should be at a level where there is no pain or a level of discomfort that the patient considers manageable.

• Patients with pain on movement following a period of inactivity and tissue stasis receive adequate analgesia prior to initiating the movement. Linking aversive levels of pain to movement can mean anticipation and fear of pain becomes more powerful than the pain itself; preventing patients fully participating in treatment that itself reduces pain.

• Those who regularly take analgesia or other psychoactive drugs like alcohol may require higher doses. If this is suspected during activity, the physiotherapist can discuss this with the patient’s prescriber.

• Care is taken that patients do not take doses that put kidney or liver function at risk. Before requesting postoperative non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or larger doses of opiates check creatinine levels and look closely at the past medical history (PMH).

• Great care is taken with the elderly. Do not use NSAIDs or larger doses of opiates with the over 70s. Relatively moderate doses of opiates or accumulating levels over time can precipitate acute confusion and permanent deterioration in memory and function, particularly in those who are not accustomed to them.

• Local and epidural anaesthetic blocks are used to help reduce or stop local pain. They enable rehabilitation despite severe pain that is less responsive to analgesics, or when a patient’s condition means therapeutic doses cannot be tolerated or are unsafe. New products including improved local anaesthetic patches and creams are becoming available all the time. Experienced staff may be able to advise you on what is available for your patients.

• Patients who don’t like taking ‘drugs’ and normally take as little as possible are encouraged not to let analgesics wear off before the next dose. Remind them: taking medication regularly in the early stages means taking less in the future; simple analgesics, even morphine, do little harm in therapeutic doses.

• If you suspect that patients are taking more than prescribed due to forgetfulness or multiple sources, e.g. over the counter and alcohol as well as prescribed, they must be warned of the risks, non-drug methods promoted, fears (which often encourage analgesia use) addressed, and the physician informed.

• Ensure paracetamol is given as well as opioid-based medication; it is a powerful painkiller. As it is an over-the-counter analgesia, patients often believe it is ‘mild’, ineffective for more severe problems. This is not the case. Care is needed to ensure the maximum daily dose is not exceeded. Care is also required for patients who take paracetamol and any analgesia on a regular and prolonged basis since these are associated with chronic medication-withdrawal headaches.

Non-drug therapy

For all patients, whether inpatient or at home, the use of non-drug methods to reduce pain and its impact, in addition to medication, should be promoted. See Box 13.1.

Box 13.1 Non-drug methods to reduce pain and its impact

• Cold or heat for injuries. Heat can be used for muscle spasm, but not in the presence of a significant healing response or inflammation. Sometimes both heat and cold can be used alternately

• Activities and conversations as distraction

• Friends, neighbours and relatives can offer reminders to limit exertion and to encourage moderate activity. The meaning of ‘appropriate rest’ must be understood so they don’t assume it means doing nothing

• Acupuncture, may provide a powerful placebo effect for many patients. It can be worth exploring for the individual patient as an aid to rehabilitation and to assist night-time sleep

• Keep the ‘pain gates’ closed as far as possible:

• If a part is too painful to move initially, advise on movements of other parts of the body before the most painful area, e.g. move the neck, shoulders and hips before the painful back

• Don’t prevent weight-bearing unless there is very good reason to. If paced, it reduces pain and swelling and increases confidence. Encourage smooth, gentle, relaxed walking for legs and spine, as ‘limp-free’ as possible; gentle pushing movements for arms. Any walking aids should have a clear wean-off programme initiated from the start to reduce future pain and disability (plus minimising loss of confidence and dependence)

Physical activity: our most potent pain reducer and aid to rehabilitation

In addition to acting on the musculoskeletal, cardiovascular, respiratory and endocrine systems, physical activity and function have an impact on the brain. Input and output to the sensory and motor cortex are sustained so that the representation of peripheral parts in the cortices is kept as normal as possible. The CNS production of pain-reducing endorphins and antidepressant monoamines is enhanced and production and impact of glucocorticoid stress hormones reduced (Duclos et al 2003). Exercise may also act as a coping mechanism and help divert patients away from negative thoughts (Box 13.2).

Box 13.2 Physical activity after surgery or injury

advice you can give to your patient

Immediately

• Calm the pain down using ‘pain gate-closing’ activities ‘little and often’ with frequent short rests for 2 days

• Reduce overall activity and rest between activities, particularly for the first 2 days, avoiding complete rest

• Relax muscles when resting and whilst moving

• Walking is the best pain-reliever, breathing exercise and basic function to support the body in recovery

• If a part feels strangely painful, weird or numb, keep touching, stroking, pressing and massaging around the area. Watch yourself doing this; it assists the brain to keep ‘in touch’ with the body

After 2 days

Gradually move and do more to:

• Improve the circulation and aid healing

• Reduce muscle spasm, checking muscles are as relaxed as possible when in use. If muscle tension/spasm builds, take more frequent rest breaks

• Don’t let chronic pain develop: move regularly, use and touch the injured part, building up to normal use, including a graded return to work or simulated work activities

From 2 weeks

• Prevent scar tissue tightening: massage external scars; stretch internal scars

• Continue to build activity. Remodelling processes respond to use: challenge them in the chronic healing stages

• Keep searching for physical concerns/fears as a result of your injury or its context: face them in a gradual and graded way with guidance

Understanding and accepting or making judgements?

Pain may be unexpectedly more or less than expected for the injury experienced, and can wax and wane over time in ways that may not always be predictable (Cronje and Williamson 2006). Patients can find this disconcerting and concerning, causing them to doubt what the health professional tells them about their condition. Health professionals have a tendency to underestimate or misidentify patients’ pain, some assume that if a patient is smiling they can’t be in pain (Kappesser and Williams 2002). Is this accurate, fair or reasonable?

Preventing chronic pain and disability

Addressing key risk factors: flags

Shaw and colleagues’ (2005) early risk factors help focus the treatment plan for yellow flags.

Patients with increased pain affecting sleep despite analgesia

What a patient does or doesn’t do in the daytime will influence the night. Daytime naps, particularly beyond lunchtime/early afternoon are disruptive to the body clock and sleep. Equally, being overactive in the daytime can increase pain, so that when the body finally rests, sleep will be prevented. Crawford (http://www.painconcern.org.uk/2011/04/leaflets/a-good-nights-sleep) gives good advice on sleep hygiene.

Belief that pain is harmful or potentially disabling

Information and patient experience are important factors for reducing fear.

Information that may help patients includes:

• The time limit of inflammation for their particular injury (maximum 7 days) and the expected healing process (maximum 3 months). Don’t mistake hypersensitivity for inflammation; pain doesn’t mean it hasn’t healed.

• An explanation of acute and chronic pain: input about the original damage is altered by central processing; how hypersensitivity develops (http://www.ppip.org.uk/viewdocuments.aspx; Butler and Moseley 2003).

• An explanation of diagnoses such as ‘degeneration’, ‘black or bulging discs’ (normal age-related changes) set in the context of pain-free populations with identical findings.

• The fact that epidemiologically the incidence of severe spinal pain and sciatica becomes increasingly less likely beyond the age of 50.

• The body’s ability to regenerate and improve the health of its tissues with the right conditions.

Intensive neurophysiology education for LBP patients can produce significant improvements in reported function and self-efficacy and physical performance tasks (SLR and forward bending range) (Moseley et al 2004). Information alone does not change behaviour for all patients (Fordyce 1976, Muncey 2002a). It is important that patients learn to change previous beliefs through actual, disconfirming experience.

Fear-avoidance behaviour from fear of pain or fear of harm/causing damage to tissues

Continuing avoidance of pain-provoking activities is a strong risk factor for chronicity and is best tackled pre-emptively when administering acute treatment and advice (e.g. Fordyce et al 1986).

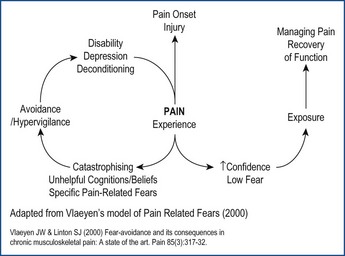

Vlaeyen and colleagues (1995, 2000) proposed a model of fear-avoidance, finding that exposure (the treatment of choice for phobias) is also effective for fear-avoidance related to pain disability (Figure 13.1).

Figure 13.1 Model of fear-avoidance.

Adapted from Vlaeyen J.W.S. and Linton S.J., 2000. Fear-avoidance and its consequences in musculoskeletal pain: a state of the art. Pain 85, 317–322. This figure has been reproduced with permission of the International Association for the Study of Pain® (IASP®). The information may not be reproduced for any other purpose without permission.

By avoiding feared movements or feelings patients fail to learn:

• How to cope with difficult situations.

• That anxious feelings do not increase to the point where they lose control or something terrible happens.

Catastrophising

Physiotherapy management strategies might include:

• Identify patient’s beliefs about the cause of their pain and its treatment.

• Explanation to help patients understand their condition.

• Where needed, challenge what patients think, feel and do about their pain.

• Educating patients about graded return to normal activity, in the presence of pain.

• Setting collaborative goal-focussed targets aimed at return to meaningful and rewarding activities.

• Providing information on pacing activity, relaxation and flare-up management.

Low mood due to the consequences of the injury

Physiotherapists will not directly treat depression, they can still have a powerful effect via:

• Increasing activity levels which directly affect mood.

• Ensuring patients feel believed.

• Ensuring patients realise that others with similar injuries recover even though pain may continue for a while.

• Encouraging patients to work towards specific activities/goals that are rewarding and meaningful to them, particularly where they thought these may be unachievable.

Expectation that passive treatments rather than active participation in therapy would help

Patients report they attend A&E or their doctor frequently, make frequent requests for medication, treatments and therapies. They seem unwilling to take their medication according to prescription, or comply with self-management strategies, e.g. ‘When I get this leg pain I usually see a marvellous physio, the manipulation really fixes it. Can you do it too?’ Robson and Gifford (2006) help us think about the actual neurobiological effects of manipulation rather than the folklore, but the psychological consequences also need consideration if it appears patients are not expecting anything other than symptomatic treatment and becoming dependent on interventional treatment (Muncey 2002b).

Patients who have significant difficulty with activities of daily living (ADL) or work for more than 4 weeks

These will be early signs of blue or black flags for which there is strong evidence for LBP (Waddell et al 2008) and whiplash-associated disorders (Burton et al 2009). Provide a strong message about the importance of being at work, and advice about light duties and a paced return to usual work.