Osteoporosis in Clinical Care

Introduction

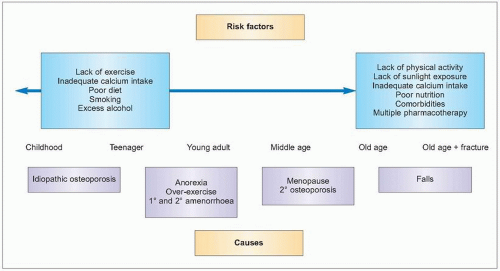

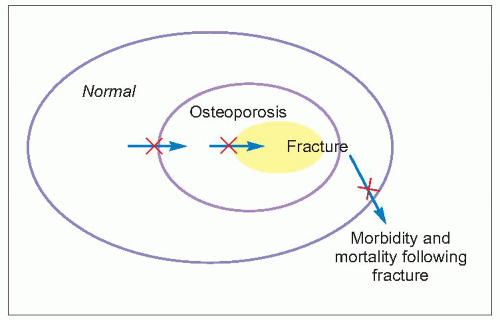

Osteoporosis is common and the burden of the resultant low-trauma fractures great and increasing. Action must be taken at all stages of life to effectively prevent and treat osteoporosis (5.1, Table 5.1). Healthy youths may develop osteoporosis in later years – it is not always predictable even in older people. It is therefore the responsibility for all to follow a bone healthy lifestyle at all stages of life, to maximise peak bone mass and prevent loss during older years. There are some who are, however, at higher risk than others of osteoporosis and fracture. These people need to be identified and treated appropriately to reduce that risk (see Chaper 3). There are also those who have osteoporosis and have sustained a fracture. It is important that they regain their independence as much as possible, as well as reduce their risk of further fracture. They need rehabilitation and often pain management. They also need treatment to improve bone strength and to reduce the risk of falls so that the risk of further fracture is reduced. In these ways the impact of osteoporosis can be lessened.

5.1 Schematic to illustrate stages when the burden of osteoporosis on the individual and on society can be reduced. |

Table 5.1 When and how to prevent osteoporosis and fracture | |

|---|---|

|

Opportunities for prevention and treatment

There are clearly some specific opportunities to recognize those at most risk and to intervene (5.2). Some of these will be considered

Childhood and adolescence

Bone mass acquired during childhood and adolescence is a key determinant of bone health in adulthood. Any factor that affects the development of the skeleton during these early years will affect attainment of peak bone mass and will have long-term consequences on bone health in later life, and increase the risk of future osteoporosis and fracture. Osteoporosis in adulthood can, therefore, have its origins already in these early years and detrimental factors to bone health need to be recognized and corrected where possible. Osteoporosis may also (rarely) manifest itself in childhood and adolescence with low-trauma fractures, such as in diseases treated with high doses of corticosteroids.

Bone development requires good nutrition along with physical stimulation in an environment of normal gonadal hormones, without the presence of noxious substances such as from smoking, excess alcohol, or corticosteroid therapy. However, the majority of bone mass and strength is determined by genetic factors which cannot as yet be modified.

In childhood and early adulthood, the commonest specific cause for inadequate bone acquisition relates to gonadal hormone deficiency which can affect both sexes. Females with late menarche and secondary amenorrhoea need to be identified and the underlying cause found and treated. Anorexia nervosa and over-exercise syndrome are common causes of low bone mass leading to premature osteoporosis and fracture. This is a consequence of poor nutrition, low body mass, and gonadal hormone deficiency.

Adequate nutrients during the growth phase are important, and lactose intolerance can result in lifelong low calcium intake. Gluten intolerance also increases the risk of future osteoporosis if not diagnosed early and treated by close adherence to an appropriate diet. Specific nutrients are

important, but the body mass index (BMI) is a simple way of estimating the overall adequacy of nutrition; it is recommended that the BMI is 19 or above.

important, but the body mass index (BMI) is a simple way of estimating the overall adequacy of nutrition; it is recommended that the BMI is 19 or above.

Steroid treatment at these ages, especially if in high doses, for diseases such as asthma, juvenile idiopathic arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosis or rheumatoid arthritis, or related to organ transplantation is a common cause of osteoporosis developing in childhood and presenting with low-trauma fracture. Cystic fibrosis now has a better survival prognosis and the complication of osteoporosis presenting with fracture is now becoming a problem affecting these children’s quality of life. Prolonged immobilization can affect skeletal development, such as related to spinal injuries or cerebral palsy.

Diagnosis of osteoporosis is difficult by bone density in the growing skeleton as it is dependent on stage of puberty (Tanner stage), and the relationship of bone density with fracture risk is not established for this age. However, it is an important age to recognize those few young people with these conditions that will put them at future risk of osteoporosis and fracture. Reversing the risk factors is most important, such as minimizing dose and duration of oral steroid use in asthma or maximizing BMI and correcting estrogen deficiency in anorexia nervosa. The evidence for specific treatments such as bisphosphonates is small and the outcome used is bone density. This is used as a surrogate for future fracture risk, but the value of bone density at this age in predicting events that may not happen for many years is not established.

Children and adolescents should be made aware of the importance of bone health and encouraged to follow a bone healthy lifestyle with regular weight-bearing exercise, adequate dietary calcium, sufficient sunlight exposure and oily fish in the diet for vitamin D, and avoiding smoking and excess alcohol. Those at specific risk need to be recognized and managed appropriately.

Case study 1

At 22 years of age, a young female was referred for assessment of bone mineral density (BMD) because of an eating disorder throughout her adolescence. She had a late menarche at 16 years and then irregular periods for 3 years and had since been receiving deoprovera injections for contraception. She had always been thin and her BMI was 16.4 when she was 18 years old. When she was assessed at 22 years her BMI was 18.5. She admitted to anorexia and also periods of bulimia. Her bone density was low with a Z-score of -2.19 in the lumbar spine and -2.05 in the proximal femur. She was counselled about her poor bone health and future risk of fracture and she was strongly recommended to improve her nutrition, to gain weight, and to use the oral combined contraceptive pill. As her grandmother had recently fractured her hip and lost her independence as a result, she followed the advice; when reassessed 2 years later she had gained 6 kg in weight, achieving a BMI of 21.5, was taking oestrogen in the form of the oral contraceptive pill, and had increased her bone density in the lumbar spine by 5.74% per annum and in the proximal femur.

Comment: Anorexia nervosa is a very important cause of low bone mass in adolescence that can lead to osteoporosis in later life. Sometimes it is severe enough to cause osteoporosis and fracture at an early age. Management is to improve diet and body weight and ensuring adequate oestrogen levels. It is often very challenging to treat as the person often has a resistance to gaining weight and they frequently do not wish to take oestrogens. Concern about osteoporosis and fracture can sometimes help encourage the person to accept a higher weight.

The gain in bone mass demonstrated in this case is exceptional with an initial rapid increase in bone density but sustained improvement, but this shows what can be achieved if there is good concordance with recommendations.

Case study 2

This 17-year-old boy has cystic fibrosis and was seen in the Osteoporosis Clinic for assessment of risk of future osteoporosis. His bone density in the lumbar spine was Z score -2.29. He had a calcium-poor diet and was not able to do a lot of physical activity, being limited by breathlessness. He was encouraged to do more weight-bearing activities and advised how he could achieve this despite impaired respiratory capacity by a physiotherapist. He was given calcium and vitamin D supplements. His bone density will be repeated in 2 years and if it worsens further compared to what would be expected for his age, then pharmacological treatment may be considered.

Comment: The outcome of cystic fibrosis has improved but with improved survival the complication of osteoporosis due to the condition, its effects on mobility and its treatment has become more of a problem. Low BMD can occur as a consequence of decreased exercise, glucocorticoid therapy, malabsorption, low body weight, and chronic infection. Adequate calcium and vitamin D is important in the diet or through supplementation, along with maximising weight-bearing activities. This will need physiotherapy advice. If bone density is very low during adolescence or early adulthood, then pharmacological treatment is used to improve it, with the aim of preventing fractures at an early age.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree