Osteoporosis and spine fractures

Stephen Brunton, Blaine Carmichael, Deborah Gold, Barry Hull, Timothy L. Kauffman, Barbara Koehler, Alexandra Papaioannou, Randolph Rasch, Hilmar H.G. Stracke and Eeric Truumees

Introduction

Osteoporosis, the most common bone disorder in humans, is a major concern for aging persons, with significant implications for morbidity and mortality. Osteoporosis is defined as a skeletal disorder with compromised bone strength as determined by bone density and bone quality. Specifically, bone mineral density (BMD) of 2.5 standard deviations or more below the young normal mean at the hip or spine is osteoporosis and osteopenia is 1–2.5 standard deviations. In the United States of America, the estimated cost of care in 2005 for osteoporotic related fractures was $17 billion (NOF, 2010). There are nearly 9 million osteoporotic-related fractures a year worldwide (WHO, 2007). There are multiple risk factors, some of which are amenable to lifestyle choices, as shown in Box 18.1.

Osteoporotic vertebral compression fractures (VCFs) represent a significant challenge to societies and health delivery systems. Individuals with a VCF experience a decreased quality of life (QOL) and also show increases in digestive and respiratory morbidities, anxiety, depression and death (Papaioannou et al., 2002; Gold, 2003; Koehler et al., 2011; Edidin et al., 2013). Most importantly, these patients have as much as a five-fold increased risk of another fracture within 1 year of the initial fracture (Lindsay et al., 2001). Up to two-thirds of VCFs are undiagnosed and, even if diagnosed, many patients are treated only acutely; few are managed long term for the prevention of fractures (Papaioannou et al., 2003b,) Thus, this chapter on osteoporosis will focus on VCFs.

According to the National Osteoporosis Foundation (NOF, 2010), primary care physicians (PCPs) need to take a proactive role in assessing the risk for or presence of VCFs and in maintaining or improving general bone health. Many patients consider back pain a normal part of aging and do not discuss it with their physician. Further, the PCP needs to act as the central point of care for a patient with a VCF, working with a spine doctor, physical therapist, clinical social worker, pharmacist and dietician to provide optimal management. To optimize interventions aimed at maintaining function and minimizing disability, all health professionals working in this field should have an in-depth understanding of the patient’s functioning and health status as well as a conceptual framework to guide communication among health professionals, clinical research and patient care. Addressing this need, the World Health Organization (WHO) has introduced the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) (Gradinger et al., 2011; Koehler et al., 2011).

The International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) of the WHO is a conceptual framework and should be used for communication among health professionals, clinical researchers and those involved in patient care.

Key points and recommendations

Key points and recommendations concerning VCFs are summarized below:

• VCFs are common but often silent consequences of osteoporosis (strength of recommendation (SOR): A).

• The risk of death is increased several-fold during the year following a VCF (SOR: B).

• The incidence of fractures can be reduced by 40–60% with pharmacological therapies (SOR: A).

SOR: A=consistent and good quality evidence. SOR: B=inconsistent or limited quality evidence. SOR C:=consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence.

Prevalence of VCFs

Of the nearly 9 million fractures that occur each year worldwide, over 1.4 million are spinal fractures (WHO, 2007). One in two women and one in five men aged 50 years and older will have an osteoporosis-related fracture (NOF, 2010). The incidence of VCF increases progressively with age and the risk for males over 65 years of age is increased. VCF are about as common in Asian as for Caucasian women and less common for African-American women (Alexandru & So, 2012).

Clinical consequences of VCFs

Active efforts to diagnose VCFs are critical because only about one-third of radiographically diagnosed VCFs cause symptoms (Black et al., 1996), often just moderate back pain. However, vertebral and other osteoporotic fractures produce cumulative and often irreversible damage (Papaioannou et al., 2002), fracture-related medical problems (Alexandru & So, 2012) and increased risk of death. For example, lung function is reduced significantly in patients with a thoracic or lumbar fracture: one thoracic compression fracture may cause a 9% loss of the forced vital capacity (FVC) (Leech et al., 1990). A four-fold higher prevalence of severe VCFs has been reported in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease than in matched controls, as well as impaired lung function as measured by the percentage decrease in FVC (Papaioannou et al., 2003b).

Multiple VCFs cause height loss, thoracic hyperkyphosis, loss of lumbar lordosis and subsequent compression of the internal organs as the spine no longer holds the body upright (Yamaguchi et al., 2005; Katzman et al., 2010). The rib cage presses on the pelvis, reducing the thoracic and abdominal space; with severe disease, this space may measure less than two finger widths. Box 18.2 provides some examples of the other effects of VCFs on a patient’s life.

Assessment and diagnosis

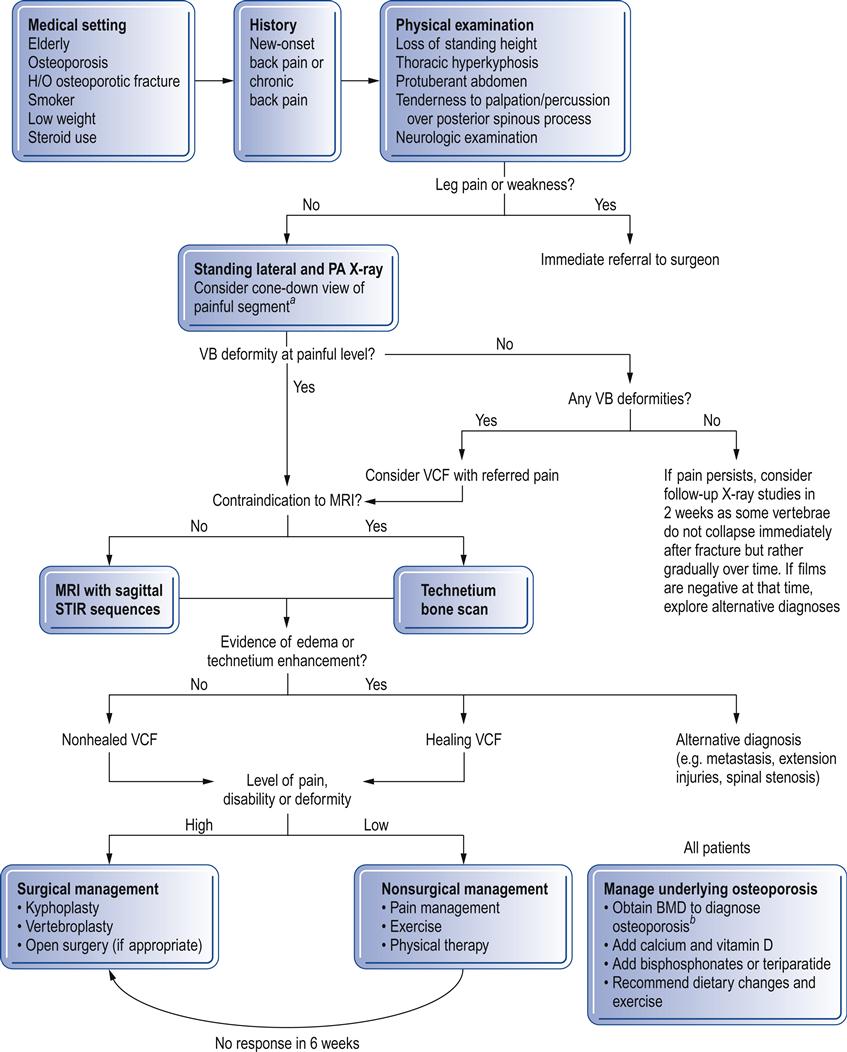

Symptomatic VCFs usually present as acute thoracic or lumbar back pain. Importantly, little correlation exists between the degree of vertebral body collapse and pain level. Evaluating the patient’s risk, taking a history, conducting a physical examination and ordering radiological studies are essential parts of the assessment and diagnosis of a suspected VCF (Fig. 18.1).

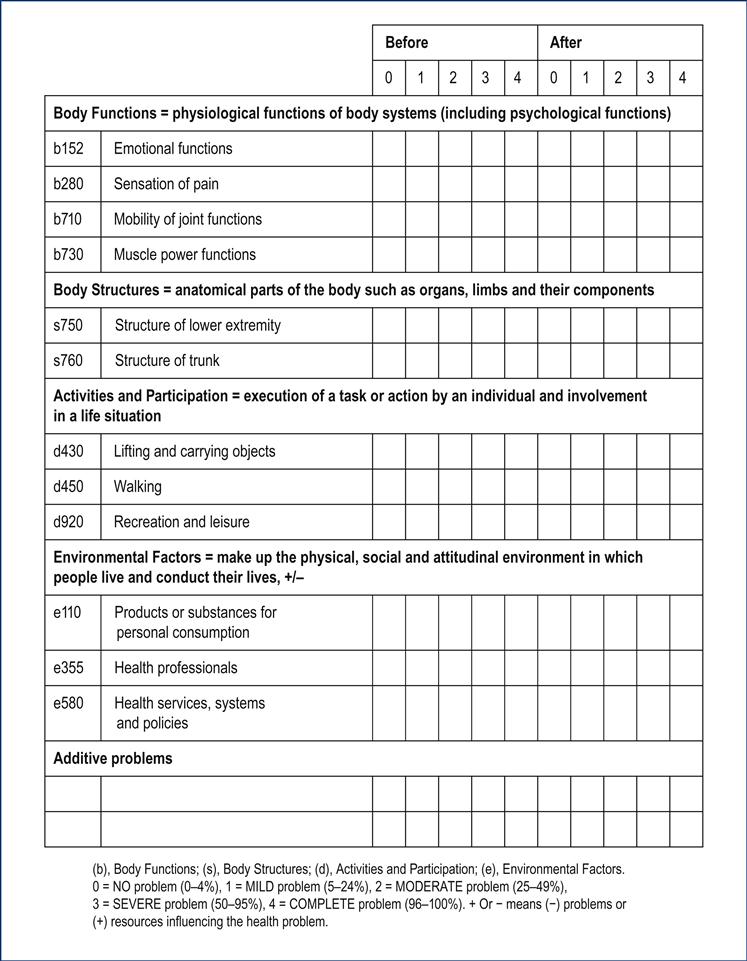

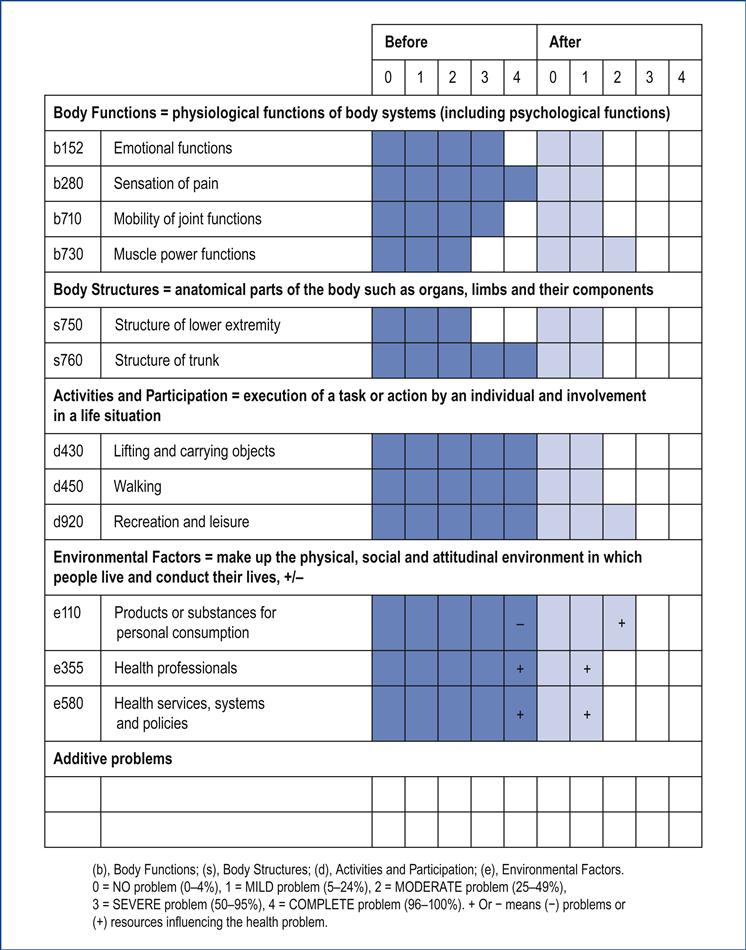

Form 18.1 shows the standardized assessment and outcome measure using the ICF Core Set for osteoporosis (brief version) that is recommended by the WHO in a modified version for use in clinical practice (Koehler et al., 2011). Form 18.2 uses information from Case Study B to show possible changes between before and after the operation by using the ICF Core Set.

Risk factors

Low bone mineral density

BMD should be tested in women age 65 and men age 70 unless there are risk factors (see Box 18.1), in which case testing may be indicated earlier (NOF, 2010). BMD is a better predictor of osteoporotic fracture than cholesterol is for coronary heart disease or blood pressure is for stroke (Tosi et al., 2004). If a patient has a fracture, the PCP should determine if the patient has had a workup for or diagnosis of osteoporosis; in the absence of a previous diagnosis of osteoporosis, the patient should be tested. Many VCFs occur in women with normal or osteopenic BMD scores, suggesting the presence of contributing risk factors, which include long-term corticosteroid use.

Patient history

Previous fracture

A history of a VCF and other fractures, for example of the wrist, is also a strong predictor of a subsequent VCF (Lindsay et al., 2001).

Diagnosis

Physical examination

The physical examination should be performed with the patient standing so that signs of osteoporosis, for example kyphoscoliosis, are more apparent. The recommended procedure is as follows. Beginning at the top and working down, depress the thumb on or over the spinous processes to examine the spine. Although VCFs can occur from the occiput to the sacrum, they most often occur in the midthoracic region and at the thoracolumbar junction (Tanigawa et al., 2012). Ask the patient to indicate the presence of pain; repeat the spine examination as necessary to pinpoint the actual pain location. Pain associated with spinal palpation may indicate a compression fracture. Often, there is an accentuation of the normal spinal contour at the level of injury with associated prominence of the spinous processes in the painful area. The presence of a spinal deformity by itself does not indicate the cause or timing of the fracture. If there is no identifiable sharp pain, suspect other age-related spine problems. Have the patient flex and extend the spine; these movements often exacerbate pain resulting from VCFs. Moderate muscle spasm or splinting may occur as the antigravity muscles of the spine attempt to unload the pressure on the wedged anterior vertebral body. A postural record can be made with a flexible ruler (Katzman et al., 2010) and a screen for balance dysfunction should be performed. A neurological examination should also be performed. In rare cases, osteomyelitis mimics symptoms of a VCF.

Other findings associated with an increased risk of osteoporosis or spinal fracture are listed in Box 18.3.