Osteonecrosis of the Hip: Arthroplasty Options

Michael A. Mont

Samik Banerjee

Bhaveen H. Kapadia

Robert Pivec

Kimona Issa

Introduction

Osteonecrosis is a pathologic bone condition caused by a disruption in the osseous circulation and impairment of normal cellular function which ultimately leads to bone infarction, osteocyte death, and joint degeneration. The incidence of osteonecrosis in the general population has been reported to be 3 per 100,000 people (1). Up to 20,000 new cases are diagnosed each year in the United States and this condition is the indication for surgery in approximately 10% of all total hip arthroplasties performed (2,3). The hip is the most common joint affected, though other commonly observed locations for osteonecrotic lesions include the knee, shoulder, wrist, and ankle (4,5,6,7). Multifocal osteonecrosis can also occur (defined as involvement of three or more joints) (1,8).

Although the exact pathogenetic mechanism for this disease still remains unclear, several direct and indirect risk factors have been implicated (Table 37.1). Direct causes are believed to disrupt normal osseous circulation or cause direct damage to osteocytes and mesenchymal cells either as a consequence of trauma (e.g., retinacular artery disruption following femoral neck fracture), vascular occlusion (e.g., sickled red blood cells or nitrogen bubbles with Caisson disease), or direct cellular damage (e.g., radiation). Indirect causes are less clearly understood and likely occur through a variety of pathophysiologic mechanisms (9). Chronic corticosteroid administration has been identified as a risk factor with doses greater than 2 gm of prednisone or equivalent increasing the risk for developing this disease. It has been hypothesized that corticosteroids lead to decreased mesenchymal cell activity and adipocyte proliferation and hypertrophy which may lead to increased intraosseous pressure (10,11). Several genetic studies have also implicated the downregulation of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in patients treated with corticosteroids (12). Another common risk factor is alcohol abuse (greater than 300 gm of alcohol consumption per day), which together with corticosteroids account for most of the cases in which a direct causative agent has not been found (13,14).

The primary goals of treatment are early diagnosis and joint preservation, which includes nonoperative measures and joint-preserving procedures. Joint arthroplasty is reserved for later-stage disease. Several radiographic grading systems have been developed to assist the surgeon in stratifying patients and choosing the appropriate treatment option (15). Although these grading systems differ, they have several common features including (1) normal plain radiographic findings with pathology visible only on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), (2) presence of a “crescent sign” (16) which indicates early femoral head collapse, (3) femoral head flattening, and (4) acetabular arthritic involvement. Joint-preserving procedures may be performed for early stages without evidence of collapse, while intermediate lesions (e.g., femoral head collapse <2 mm) may be candidates for joint-preserving procedures such as bone grafting (17,18,19,20) and rotational or proximal femoral

varus osteotomies (21,22,23). However, total hip arthroplasty is usually required in advanced cases where there are large lesions, greater than 2-mm deformation of the femoral head, or acetabular arthritic involvement (24,25,26).

varus osteotomies (21,22,23). However, total hip arthroplasty is usually required in advanced cases where there are large lesions, greater than 2-mm deformation of the femoral head, or acetabular arthritic involvement (24,25,26).

Table 37.1 Direct and Indirect Risk Factors for Developing Osteonecrosis | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

With these basic considerations in mind, concerning osteonecrosis of the femoral head, this chapter will discuss pre- and postoperative considerations, including radiographic interpretation, surgical technique, and options, as well as results, and complications.

Clinical Evaluation

Developing a treatment plan for patients who have osteonecrosis of the femoral head requires appropriate clinical, radiographic, and intraoperative evaluations. Early diagnosis remains the key to successful head-salvaging treatments. An understanding of the different associated factors for osteonecrosis may help a clinician diagnose these patients early who present with groin pain. In the patient who has radiographically demonstrable osteonecrosis several considerations must be made before deciding on a treatment plan.

Signs and Symptoms

Patients typically present with groin pain, although 10% to 15% may have nonspecific symptoms such as trochanteric or buttock pain. It is sometimes reasonable to consider a diagnostic hip injection with a local anesthetic to rule out other pathology such as lumbar disc disease. Often a patient with occult osteonecrosis may have nonspecific hip, trochanteric, or buttock symptoms that radiate from the back or another pathologic entity.

Patient-Specific Factors

The patient’s age, activity level, general health, and prior surgical history help to individualize the proposed treatment. The presence of severe systemic illness or a short life expectancy may preclude a major surgical procedure or may lead to the decision to perform one definitive procedure (arthroplasty). However, a young patient may better tolerate surgical procedures, so preservation attempts are appropriate or if arthroplasty is necessary they may require a more durable bearing surface. Thus, similar lesions may need to be treated in different ways depending on the patient history, demographic variables, lifestyle demands, and activity levels.

For example, a unifocal osteonecrotic lesion in the hip of an active, 34-year-old patient with a prior vascularized free fibular graft will require different instrumentation, approaches, and choice of components than a lower demand 65-year-old patient who developed a similarly located and sized lesion as a consequence of chemotherapy for a malignancy. In the first case, revision of a bone-grafting procedure may require special surgical equipment and lead to a longer operative time whereas the second case is likely to be a relatively uncomplicated arthroplasty. Conversely, bearing choice is far more critical in the first case where the patient needs a durable bearing surface and a stable hip through a large range of motion arc, unlike the second case where the patient who is relatively less active may suffice with a traditional bearing option.

Prior surgical procedures may increase the difficulty of performing an arthroplasty and must be considered prior to surgery. Although many patients who have undergone prior surgical procedures will likely have received a core decompression or percutaneous drilling, that facilitates easy component placement, dysplastic patients who have undergone osteotomies or vascularized fibular grafting may present with retained hardware. Similarly, patients who present with posttraumatic osteonecrosis may have sustained multiple extremity injuries, and apart from hardware present in the hip joint area there may be anterograde or retrograde femoral nails, or in less common cases, femoral plates, which may make placement of a femoral stem for a hip arthroplasty difficult and increase surgical morbidity because of the need for multiple incisions, increased operative time, and potential blood loss. In the posttrauma setting, it has been estimated that 15% of all hardware removals are performed in preparation for total hip arthroplasty (27). With femoral nails in particular, unreamed nails may become incarcerated, thus making removal difficult. Furthermore, the removal of proximal interlocking screws may potentially create a stress riser or risk for refracture (28,29). Even after successful nail removal, up to 20% of patients have reported residual pain, which may affect their perceived satisfaction with their total hip arthroplasty (30).

One should consider that this disease is often bilateral (range, between 50% and 100%, with bilaterality greater than 80% in some large series). When planning treatment, the surgeon may consider staging hip arthroplasties to allow for the patient to rehabilitate one hip before proceeding to the contralateral side. However, if a small procedure (e.g., core decompression) is planned for one side, then performing both procedures at one sitting is appropriate. In general, as with osteoarthritis, the more clinically symptomatic hip should be addressed first, unless one is trying to save the less symptomatic hip. Of note is that in approximately 10% of patients, other joints exhibit osteonecrosis. If a patient has pain in other joints, such as the knee, shoulder, or ankle, they should be investigated with radiographs and possibly an MRI to describe further disease and to develop a treatment plan.

The etiology of the osteonecrotic lesion should always be considered since the presence of some risk factors may predispose patients to additional postoperative complications, such as delayed wound healing or infection. In particular, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection and associated antiretroviral therapy have been implicated as causes of osteonecrosis and poor outcomes (31). These patients, however, have been observed to have higher rates of periprosthetic infection as a consequence of their immunodeficient state (32,33,34). In a recent study of HIV-positive patients who underwent lower extremity total joint arthroplasty, 29% (6 of 21 joints) developed a periprosthetic infection at a mean follow-up of 10 years (35).

In summary, numerous clinical factors including age, etiology of disease, and patient comorbidities may influence the choice of treatment for osteonecrosis of the femoral head. However, radiographic factors and staging should typically take precedence over these factors. For example, even

though a teenager might prefer avoiding a total hip arthroplasty, this choice may not be appropriate if radiographically detectable arthritic changes are present on both sides of the joint. In the next section we discuss the relevant radiographic factors that should be evaluated with these patient-specific factors to create an appropriate treatment plan.

though a teenager might prefer avoiding a total hip arthroplasty, this choice may not be appropriate if radiographically detectable arthritic changes are present on both sides of the joint. In the next section we discuss the relevant radiographic factors that should be evaluated with these patient-specific factors to create an appropriate treatment plan.

Radiographic Evaluation

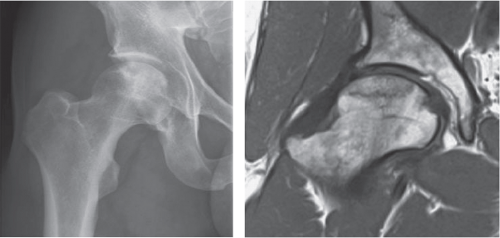

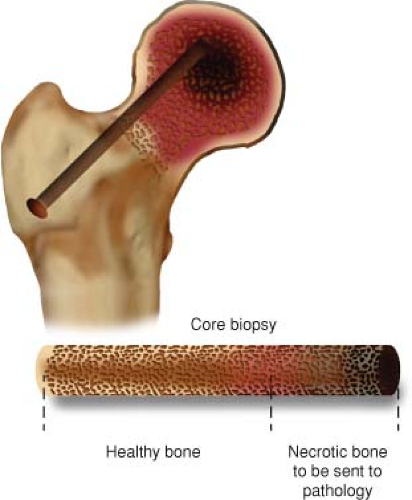

If a patient presents with risk factors for osteonecrosis and groin pain, it is imperative to evaluate the patient with x-rays and MRI; the mainstays in the initial evaluation of these patients. MRI has an extremely high sensitivity and specificity for this diagnosis, on the order of 99% or greater (Fig. 37.1) (36). Nuclear bone scintigraphy is not as sensitive and may miss the diagnosis in more than 20% of lesions so they are not indicated. Scintigraphy was initially thought to be cost-effective (37), however, one can now obtain a limited cost-effective MRI sequence that can lead to the diagnosis (38). In addition, the authors believe that computed tomography (CT) scans (tomograms) have limited value, because of unnecessary radiation exposure and should only be used if one is trying to rule out collapse. Invasive tests, such as intraosseous pressure measurements or core biopsy, are not necessary for making the diagnosis.

Table 37.2 Overview of Commonly Utilized Plain Radiographic Staging Systems | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Numerous classification systems have been used to describe the radiographic extent of osteonecrosis of the femoral head. Each system has its limitations, and no single system is presently accepted as the sole guide to treatment. The most commonly used systems are summarized in Table 37.2. In formulating a treatment plan, the authors use

four essential radiographic findings that have been shown in multiple studies to have prognostic value. The lesion should be classified with regard to collapse; a precollapse or postcollapse lesion. Precollapse lesions have the best prognosis and do not immediately require total hip arthroplasty. The size of the necrotic segment must be assessed, since large lesions are at the highest risk for progression and are often better treated definitively with total hip arthroplasty. The next feature of importance is the amount of head depression. Lesions with less than 2 mm of head depression have a more favorable outcome and joint salvage may be attempted, whereas greater than 2 mm of depression is a poor prognostic indicator. Acetabular involvement should be characterized, as any sign of osteoarthritis will limit treatment options typically to hip arthroplasty.

four essential radiographic findings that have been shown in multiple studies to have prognostic value. The lesion should be classified with regard to collapse; a precollapse or postcollapse lesion. Precollapse lesions have the best prognosis and do not immediately require total hip arthroplasty. The size of the necrotic segment must be assessed, since large lesions are at the highest risk for progression and are often better treated definitively with total hip arthroplasty. The next feature of importance is the amount of head depression. Lesions with less than 2 mm of head depression have a more favorable outcome and joint salvage may be attempted, whereas greater than 2 mm of depression is a poor prognostic indicator. Acetabular involvement should be characterized, as any sign of osteoarthritis will limit treatment options typically to hip arthroplasty.

Table 37.3 Combined Necrotic Angle (Kerboul) Lesion Size Stratification | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Precollapse Versus Postcollapse

Collapse represents mechanical failure of the weakened necrotic bone. Although large areas of collapse can be recognized by a change in the contour of the femoral head, this may not be as obvious in heads without substantial depression. An early indicator is the crescent sign (16). When collapse is present it is likely that the patient will eventually require a total hip arthroplasty and attempting head-preserving procedures will likely only increase surgical morbidity as a consequence of further procedures secondary to disease progression (39). Collapse may be characterized using CT scans in some lesions (40).