Osteochondritis Dissecans and Avascular Necrosis

Matthew T. Burrus

David R. Diduch

DEFINITION

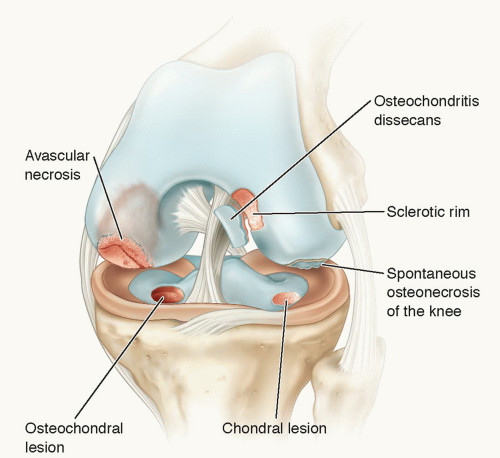

Osteochondritis dissecans (OCD), avascular necrosis (AVN), spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee, and chondral and osteochondral lesions all occur at or beneath the articular surface of a weight-bearing joint and are easily confused (FIG 1).

OCD lesions occur when a segment of subchondral bone becomes avascular. The wafer of bone plus the overlying articular cartilage may become separated from the underlying bone.

Chondral lesions on the articular surface do not penetrate subchondral bone; damage is to chondrocytes and extracellular matrix and there is no inflammatory healing response.

Osteochondral lesions not only damage articular cartilage but also penetrate subchondral bone and, therefore, cause an inflammatory healing response.

AVN occurs when a larger wedge segment of bone loses its blood supply. If the necrosis extends to the subchondral bone, this can lead to subchondral fracture and bone surface collapse.

In OCD, the avascular fragment separates from a normal, vascular bony bed beneath a sclerotic rim. In AVN, the avascular osteochondral surface breaks into multiple fragments and separates from an avascular bed.

Spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee involves a stress fracture of the subchondral bone with secondary collapse. It often is seen in patients postmeniscectomy or with meniscal subluxation.

ANATOMY

Osteochondritis Dissecans

OCD lesions most often are found in the knee. They also occur commonly in the capitellum and talus.

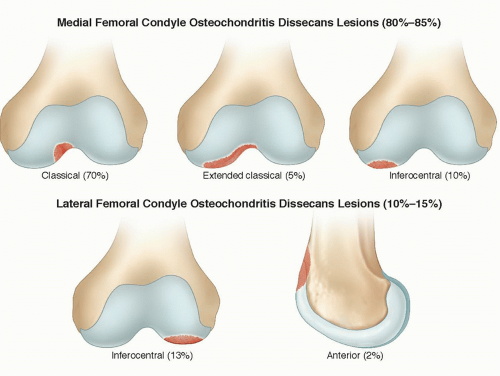

In the knee, OCD lesions involve the medial femoral condyle 80% to 85% of the time, the lateral femoral condyle 10% to 15% of the time, and the trochlea less than 1% of the time. Patellar lesions are uncommon, seen in only 5% to 10% of cases, and typically occur in the inferomedial area.10,16,20

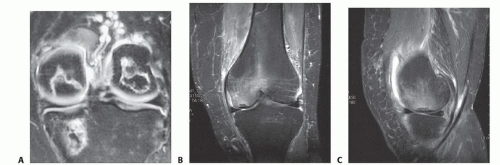

Classic lesions occur in the lateral aspect of the medial femoral condyle. Lateral lesions most often are located in the inferocentral region and involve a significant portion of the weight-bearing surface (FIG 2).

Avascular Necrosis

AVN most commonly is seen in the hip. The knee is the second most common location but accounts for only about 10% as many cases as the hip. AVN can affect the femur, tibia, or both; is bilateral in over 80% of cases; and usually involves multiple condyles (FIG 3A).

AVN involves a larger area of subchondral bone, with extension into the epiphysis and even the metaphysis or diaphysis.

Spontaneous Osteonecrosis of the Knee

Spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee is different from AVN. Spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee occurs in patients older than 55 years, involves only one condyle (most commonly medial), and is unilateral in 99% of cases (FIG 3B,C).

The pathologic lesion in spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee is a stress fracture of subchondral bone with collapse of the articular surface and secondary joint incongruity and pain.

PATHOGENESIS

Osteochondritis Dissecans

The definitive cause of OCD lesions remains elusive. Several theories exist, including trauma, ischemia, abnormal ossification involving the physes, genetic predisposition, and combinations of these. Prominent theories are further discussed in the following paragraphs, with most authors suspecting that repetitive stress plays a central role.

Repetitive microtrauma may create a stress fracture within subchondral bone. If the microtrauma continues and overwhelms

the ability of the subchondral bone to heal, necrosis may occur, leading to separation and nonunion of the segment.10

FIG 2 • Locations of OCD in the knee. (Adapted from Williams JS Jr, Bush-Joseph CA, Bach BR Jr. Osteochondritis dissecans of the knee. Am J Knee Surg 1998;11:221-232.)

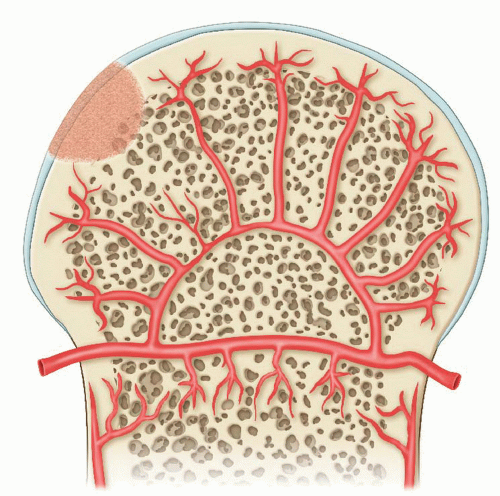

The epiphyseal artery supplies the epiphysis and secondary centers of ossification.

The alteration of subchondral vascularity is precipitated by insult at a vulnerable point.

In juvenile cases, revascularization can occur.

In most situations, however, healing is inadequate, and persistent avascularity of the fragment, along with mechanical forces at the subchondral region, leads to articular surface fracture.

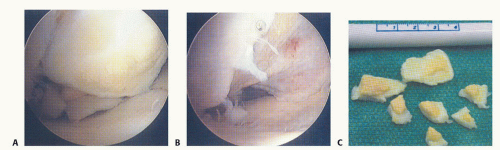

Synovial fluid pumped into the bone around the fragment via knee motion limits healing by preventing fibrin clot formation. The pressurized fluid can even erode bone and create a cystic defect. Loss of fragment stability results in loose body formation.

Shear stress may be created by the medial tibial spine abutting the medial femoral condyle, possibly coupled with traction from the posterior cruciate ligament origin. However, this theory does not account for the presence of lesions at other locations and the fact that tibial eminence impingement does not occur in connection with normal walking or running.

Avascular Necrosis

AVN of the knee has been called ischemic, idiopathic, or corticosteroid-associated necrosis.

As with AVN of the hip, necrotic bone leads to subchondral fracture and subsequent joint collapse.11

Similar to OCD lesions, AVN occurs from interruption of blood supply to a segment of bone, but in AVN, the interruption is atraumatic and may involve the epiphysis and also extend into the metaphysis.

NATURAL HISTORY

Osteochondritis Dissecans

OCD lesions occur in between 15 and 21 per 100,000 people, with a peak between the ages of 10 and 15 years.

They are more common in males, by a 5:3 ratio.

A history of previous knee trauma is seen in 40% to 60% of patients.

Lesions are bilateral in 15% to 30% of patients, usually prompting evaluation of both knees after making the diagnosis.

If lesions are bilateral, they typically are in different phases of development.

Patient maturity aids in prediction of treatment outcome.

Juvenile cases with open physes have a high (65% to 75%) potential to heal.

Results in adolescent cases are less predictable. About 50% do go on to heal, but the remainder have a progressive, nonhealing course similar to that of adult (ie, patients with closed physes) patients.

In skeletally mature patients, healing potential is essentially nonexistent.

Factors affecting prognosis include size and site of the lesion, fragment stability, joint fluid behind the fragment, status of the articular surface, and duration of the disorder.

Avascular Necrosis

AVN of the knee occurs most often in patients younger than 55 years of age, involves multiple condyles, and is bilateral more than 80% of the time.

Patients have AVN in other large joints in 60% to 90% of cases; are predominantly women; and often have a history of systemic lupus erythematosus, sickle cell disease, alcoholism, or systemic corticosteroid use.

In general, only AVN involving the epiphysis is clinically important. Here, loss of structural support can lead to collapse and fragmentation of the overlying joint surface, resulting in a painful arthritic joint (FIG 5).

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

Osteochondritis Dissecans

Vague, poorly localized complaints of knee pain often are the initial presentation for OCD lesions.

Swelling is important to note because an effusion strongly suggests that the fragment is loose to at least some degree.

Loose or detached lesions may have mechanical symptoms such as crepitus, catching, or locking. These symptoms can mimic meniscal pathology.

Symptoms tend to progress with time, as continued activity causes a stable lesion to become unstable.

Quadriceps atrophy may be present as a late finding with chronic lesions.

Loss of range of motion is uncommon. Pain with range of motion, crepitus, or mechanical symptoms may represent an unstable lesion.

Wilson sign is specific for medial femoral condyle lesions and is tested for by flexing the knee to 90 degrees, then internally rotating and slowly extending it.

Patients develop pain (positive Wilson sign) at approximately 30 degrees as the tibial spine abuts against the medial femoral condyle; pain is relieved with external rotation.

According to recent studies, this sign may lack sensitivity.20

Patients may walk with an antalgic gait, externally rotating the affected leg to avoid contact of the tibial spine against the medial femoral condyle in the classic lesion.

Tenderness to direct palpation of the lesion (Axhausen sign) is found in patients with subchondral instability and is a helpful indicator of progressive healing as the sign abates.

Avascular Necrosis

Patients with AVN have insidious onset of knee pain.

The pain may be medial, lateral, or diffuse.

Mild effusions and joint line tenderness may be present.

The physical examination often is unremarkable.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Osteochondritis Dissecans

In OCD, plain films help to localize and characterize the lesion while also providing valuable information regarding skeletal maturity and age of the lesion and ruling out other bony injuries.

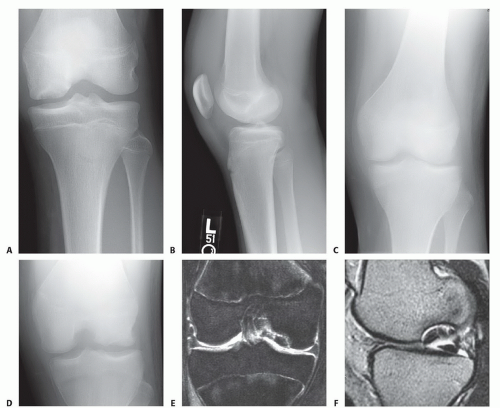

Radiographic evaluation should include anteroposterior (AP), lateral, tunnel, and sunrise views (FIG 6A,B).

Tunnel views provide visualization of the femoral condyles in greater profile than can be obtained with AP views (FIG 6C,D). The tunnel view often is the most revealing view because OCD lesions commonly are located on the lateral aspect of the medial femoral condyle.

Comparison views of the opposite knee should be considered because 15% to 30% of cases are bilateral.

Children younger than 7 years of age may have irregularities of the distal femoral ossification centers that simulate OCD lesions. These represent anatomic variants of normal ossification and are asymptomatic.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is an essential part of the diagnostic evaluation of OCD.

It provides critical information regarding the status of cartilage and subchondral bone, size of the lesion, presence of fluid beneath the lesion, extent of bony edema as well as loose bodies or other knee injuries (FIG 6E,F).

De Smet et al5 found four MRI criteria that are negatively correlated with the ability of OCD lesions to heal after nonoperative treatment: a line of high signal intensity beneath the lesion, indicating synovial fluid, that (1) is at least 5 mm long, (2) is at least 5 mm thick, or (3) communicates with the joint surface, and (4) has a focal defect of 5 mm or more in the articular surface.

A 2008 retrospective study evaluating the sensitivity and specificity of defining lesion instability on MRI looked at 36 juvenile and 34 adult OCD lesions. By defining radiographic instability as (1) high T2 signal intensity rim, (2) surrounding cysts, (3) high T2 signal intensity cartilage fracture line, (4) fluid-filled osteochondral defect, the criteria was 100% sensitive and 11% specific for juveniles and 100% sensitive and specific in adults.8

Despite the widespread use of MRI in evaluating OCD lesions, Quatman et al14 felt that, after a review of the current literature, no high-quality studies have consistently

verified MRI results with arthroscopy findings. They cite lack of standardized grading criteria and variations in imaging sequences as part of the discrepancy.14

Historically, Cahill and Berg3 advocated the use of serial technetium 99m bone scans for evaluation of healing. This recommendation was based on the relation between blood flow and osteoblastic activity with scintigraphic activity.

Unfortunately, the isotropic tracer remains in the affected area well after healing, making interpretation difficult.

The use of serial bone scans for the management of OCD lesions has not been universally accepted, in large part because of the need for intravenous access, time required for the study, and, more importantly, the emergence of MRI.

Avascular Necrosis

For patients with AVN, plain radiographs and MRI scans should be obtained.

Once the diagnosis of AVN is established, screening MRI of both hips should be considered.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Normal accessory ossification centers

Loose bodies

Meniscus pathology

Acute osteochondral fracture

Avascular necrosis

Epiphyseal dysplasia

NONOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

Osteochondritis Dissecans

Initial nonoperative treatment is indicated in children with open physes because of the favorable natural history in this patient population.

Most authors agree that 6 weeks of protected weight bearing followed by 6 weeks of activity modification and reevaluation with radiographs plus MRI at 3 months constitutes an adequate trial of nonoperative treatment.

Cahill2 reported that 50% of juvenile OCD lesions will heal within 10 to 18 months if the physis remains open and patient compliance is maintained.

In a study of 47 knees, two-thirds of juvenile OCD lesions deemed stable on MRI healed within 6 months with activity modification and temporary immobilization alone. Significant risk factors for a nonhealing lesion were increased size of the lesion and swelling and/or mechanical symptoms upon presentation.18

Children present unique challenges with regard to compliance.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree