15 Osteoarthritis and crystal arthropathies

Cases relevant to this chapter

Essential facts

1. Osteoarthritis (OA) is the clinical and pathological outcome of a range of factors that lead to pain, disability and structural failure in synovial joints.

2. By the age of 65 years, 80% of people have radiographic evidence of OA affecting the spine, hips, knees, hands and feet, but only one in four are symptomatic.

3. OA is a dynamic process of remodelling and proliferation of new bone, cartilage and connective tissues, as well as focal degeneration of articular cartilage.

4. Insidious pain occurs as a result of increased pressure or microfractures in the subchondral bone, low-grade synovitis, inflammatory effusions, capsular distension, enthesitis or muscle spasm, and nocturnal aching may be associated with hyperaemia in the subchondral bone.

5. Consider a predisposing underlying condition in patients with OA before the age of 40 years or if OA develops in unusual sites.

6. Medical treatment of OA is to relieve symptoms, maintain and improve joint function, and minimize disability and handicap; optimal management requires a combination of non-pharmacological and pharmacological modalities.

7. Surgical management of OA is indicated where medical therapy has failed; joint replacement is effective and cost-effective, irrespective of age.

8. Calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate crystals are deposited at entheses, in hyaline cartilage and in fibrocartilage, and are associated with chondrocalcinosis and degenerative changes; shedding of crystals into joints can provoke acute synovitis (pseudogout) or chronic pyrophosphate arthropathy.

9. Acute gout usually presents as monoarthritis in a distal joint of the foot or hand.

10. Recurrent attacks of gout cause progressive cartilage and bone erosion, deposition of palpable masses of urate crystals (‘tophi’), and an asymmetrical erosive inflammatory polyarthritis. Gout is now the commonest type of chronic inflammatory arthritis.

Osteoarthritis

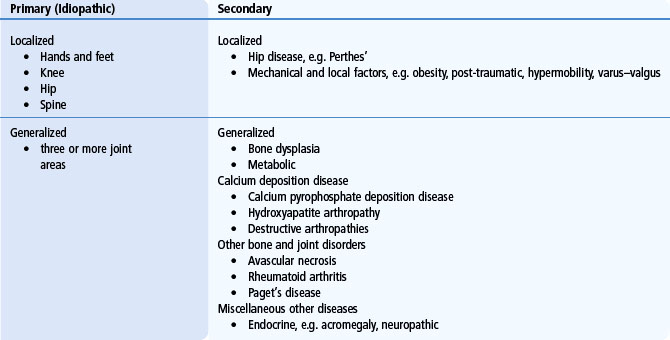

Osteoarthritis (OA), also sometimes called osteoarthrosis or degenerative joint disease, is not a single disease, but rather the clinical and pathological outcome of a range of disorders and conditions that lead to pain, disability and structural failure in synovial joints. OA is classified as being primary (idiopathic) or secondary, when it follows some clearly defined predisposing disorder or disease (Table 15.1), but the development of all types of OA is associated with multiple aetiological factors.

Epidemiology

OA is the commonest type of arthritis. Radiographic and autopsy surveys show a steady age-related increase in prevalence from the age of 30 years. By the age of 65 years, 80% of people have some radiographic evidence of OA, although only one in four is symptomatic. The joints most frequently affected are the spine, hips, knees, and some of the small joints of the hands and feet (Fig. 15.1). Community-based studies in the UK have shown that 10% of the population over the age of 55 years have troublesome knee pain and, of those, 25% are severely disabled. OA is the leading cause of physical disability in people age over 65 years. The prevalence of both radiographically defined OA and OA-related disability is greater in women than in men. Although disability associated with OA also increases steadily with age, the majority of people with OA-related disability in the community are between the ages of 55 and 75 years.

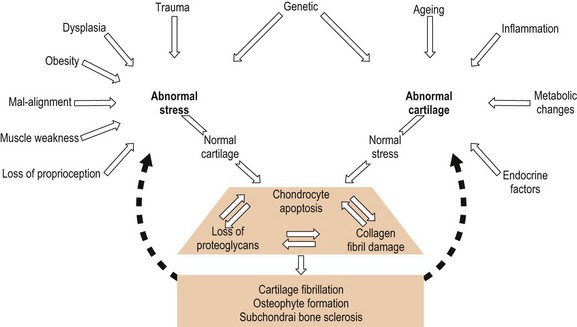

Risk factors for OA include constitutional factors such as age, sex, the shape and alignment of joints, obesity and some genetic determinants, but there are also important environmental triggers, such as previous injury or the repetitive trauma associated with certain recreational activities, such as weightlifting or long-distance running, and with some occupations, such as mining and farming. Mechanical factors play a role in the pathogenesis of all types of primary, as well as secondary, OA. Joint failure occurs when mechanical stresses overwhelm the capacity of articular tissues to resist and repair the damage. Structural failure of the articular cartilage, bone and periarticular tissues can result from abnormal mechanical stresses damaging previously normal tissues, or from the failure of pathologically impaired joint tissues in response to physiologically normal mechanical forces (Fig. 15.2). Obesity, joint mal-alignment, occupational trauma and muscle weakness are all important, potentially modifiable, biomechanical risk factors that determine the site and severity of the disease. Race and ethnicity have some influence on the probability of developing OA at different sites. Although OA of the knee is prevalent in all ethnic groups (particularly frequent in black women), hip, hand and generalized OA are seen predominantly in Caucasians. Genetic factors are known to be important determinants. Twin studies suggest heritability of up to 65% in primary OA of the hand and knee, but the susceptibility genes themselves still remain largely undefined.

Progress has been made in identifying mutations in collagen genes that are associated with different types of bone and cartilage dysplasia where OA is part of a more complex phenotype, but none of these single gene mutations in genes that code for structural matrix proteins appears to be important in determining susceptibility to the common types of OA. Recently, however, there has been some progress in identifying a promoter polymorphism in a bone morphogenetic protein (growth differentiation factor 5) that is associated with both hip and knee OA, as well as other polymorphisms in genes that code for signalling proteins involved in the development and maintenance of articular cartilage, which appear to be associated with susceptibility to hip OA in certain ethnic groups (see Chapter 3).

Pathology and pathogenesis

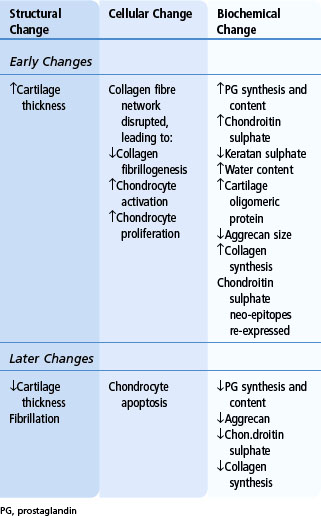

OA involves all tissues of the joint (subchondral bone, ligaments, capsule and synovial membrane) as well as the articular cartilage, but inflammatory changes in the synovium are usually minor and secondary. To a variable extent OA is a dynamic process characterized by remodelling of the anatomy of the joint and proliferation of new bone in the form of osteophytes, as well as by focal degeneration of articular cartilage. In many cases these processes reach a state of non-progressive equilibrium, but in others there is symptomatic failure of the joint characterized by progressive degeneration of the articular cartilage with fibrillation, fissuring, ulceration and, eventually, full-thickness focal loss of cartilage at sites of joint loading. In addition, with wear, there is compaction and sclerosis (‘eburnation’) of the adjacent subchondral bone and the formation of bone cysts (Fig. 15.3). The biomechanical properties of the cortical and subchondral bone play an important role in protecting articular cartilage following impact loading. It is suggested that the pathogenesis of OA in some cases may be initiated by an increase in the density and stiffness of the subchondral bone following the healing of microfractures caused by unprotected loading of joints. The consequent loss of bone viscoelasticity results in steep stiffness gradients in the bone. This in turn results in stretching and fibrillation of the overlying articular cartilage, as well as focal osteonecrosis and the formation of bone cysts. In support of this hypothesis, patients with hip and knee OA have higher than normal bone mass and there is evidence that focal increases in subchondral bone density can precede and predict future cartilage loss in patients with OA of the knee. The sequence of pathological and biochemical changes in the articular cartilage in OA follows a characteristic pattern (Table 15.2), whether primary or secondary to changes in the subchondral bone. Early increases in matrix hydration and articular cartilage thickness follow disruption of the collagen fibre network, loss of tensile strength in the superficial zone of the articular cartilage and swelling of the negatively charged, high-molecular-weight proteoglycan, aggrecan. Initially, chondrocyte activation and proliferation of clusters of chondrocytes are associated with an anabolic response with increased synthesis and turnover of matrix collagens and proteoglycans, but in the later stages of OA, catabolism of cartilage matrix proteins outstrips the capacity for cartilage repair. Anabolic mediators include growth factors, such as the insulin-like growth factor (IGF-1), fibroblast growth factor (FGF), transforming growth factor β (TGFβ) and the bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs): the anti-inflammatory cytokine interleukin (IL)-4 and proteinase inhibitors, such as tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases (TIMPs) and plasminogen activator inhibitor (PAI). Catabolic mediators include nitric oxide, prostaglandins and the pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1β, tumour necrosis factor (TNFα), IL-6 and IL-17, as well as metalloproteinases (MMP-1, -8, and -13) and aggrecanases (ADAM-TS-4 and -5).

Common clinical presentations

The salient features of the common types of hip, knee, hand and nodal generalized OA are summarized in Table 15.3.

Table 15.3 Common clinical types/patterns of osteoarthritis

| Knee Osteoarthritis | Hip Osteoarthritis | Hand Osteoarthritis |

|---|---|---|

| Patello-femoral and medial joint compartments | Supero-lateral or central (medial or polar) | Distal interphalangeal and proximal interphalangeal joints, carpometacarpal (CMC) joints of the thumbs |

| Knee pain Pain on walking ↑uneven ground ↑stairs Antalgic gait Difficulty rising from chairs | Groin pain → thigh/medial side of the knee → buttock Antalgic gait Difficulty with socks and toenails | Pain/swelling/stiffness + Restricted movements Symptoms often settle Hand function preserved Frequent family history |

| Bilateral > unilateral | Unilateral > bilateral | Usually bilateral |

| Women > men | Women > men | Women > men Perimenopausal onset |

| Varus > valgus or Fixed flexion deformities Joint-line tenderness Joint-line bony swelling Crepitus Quads muscle wasting | Pain/restricted movements: internal rotation (early), external rotation/abduction (later) Fixed flexion/ext. rotation Limb shortening Quads/gluteal muscle weakness and/or wasting | Heberden nodes ± Bouchard nodes Subluxation 1st CMC Squaring of hand Associated with OA in other joints (especially knees and medial OA of the hips) |

Atypical and ‘secondary’ osteoarthritis

The possibility of some defined predisposing underlying condition (see Table 15.1) needs to be considered, particularly in patients who develop typical symptoms and signs of OA before the age of 40 years, in those who develop OA in joints that are usually not affected, and in those with certain characteristic patterns of joint involvement. A history of major preceding trauma, such as a fracture that resulted in articular cartilage damage or subsequent mal-alignment, is often found to be the cause of monoarticular OA developing at an early age or in a joint, such as the ankle, that is seldom otherwise affected. Nearly 50% of patients have knee OA 21 years after open meniscectomy, and the average time to develop hip OA following a fracture dislocation is 7 years. Early-onset OA with prominent involvement of the second and third metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joints is very characteristic in patients with haemochromatosis and may be an early clinical clue that leads to establishment of the diagnosis (for more details see Chapter 14). Although deposition of calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate (CPPD) and basic calcium phosphate (BCP or apatite) crystals is common in articular cartilage in OA, the possibility of familial CPPD disease should be considered in patients presenting with premature knee OA. This is especially important when the knee OA is accompanied by frequent inflammatory episodes or prominent hypertrophic radiographic features, and in patients presenting with OA in relatively atypical joints, such as the shoulder, elbow or radiocarpal joints in the wrists.

Management

Non-pharmacological modalities of therapy

• All patients should be provided with information and education about the objectives of treatment and the importance of changes in lifestyle, exercise, weight reduction, and other measures to unload the damaged joint. The initial focus should be on self-help and patient-driven treatments, rather than on passive therapies delivered by health professionals.

• All patients with lower-limb OA should be given advice about appropriate footwear with thick, soft soles. Laterally wedged insoles can give symptomatic relief to some patients with medial tibio-femoral compartment knee OA.

• Patients with symptomatic OA of the hip or knee can benefit from referral to a physiotherapist for: (a) assessment and instruction in appropriate exercises to reduce pain and improve functional capacity, and (b) assessment and provision and instruction in the use of a stick or walker in appropriate circumstances.

• Patients with hip and knee OA should be encouraged to undertake and continue with regular aerobic, muscle-strengthening and range-of-movement exercises. Pool exercises can be effective in patients with symptomatic hip OA associated with muscle spasm.

• Patellar taping can provide short-term symptom relief in some patients with patello-femoral OA.

• A knee brace can reduce pain, improve stability and reduce the risk of falls in patients with knee OA associated with mild/moderate varus or vagus instability.

• Heat packs, ice packs, acupuncture and transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation have all been shown to be effective for helping with short-term pain control in some patients with knee OA in controlled trials.

Pharmacological modalities of therapy

• Paracetamol (up to 3 g daily) should be the analgesic of first choice for patients with symptomatic OA.

• In patients who do not respond adequately to a trial of paracetamol, the choice of alternative or additional analgesics needs to take into account both the relative efficacy and safety of the drug or drug combination being considered as well as concomitant medication and co-morbidities.

• In some patients who do not respond adequately to paracetamol, NSAIDs at the lowest effective doses can be added or substituted, but long-term use of NSAIDs should be avoided if possible. In patients with increased gastrointestinal risk, a cyclo-oxygenase (COX) 2 selective agent or a non-selective NSAID with co-prescription of a proton pump inhibitor or misoprostol for gastroprotection can be considered.

• All NSAIDs (including COX2-selective agents) should be used with caution in patients with cardiovascular risk factors.

• Topical NSAIDs or topical capsaicin can be effective as adjuncts or alternatives to oral analgesics in some patients with symptomatic knee OA.

• Intra-articular injections with corticosteroids can be considered in patients with moderate to severe pain who are not responding adequately to oral analgesic/anti-inflammatory agents, and in patients with symptomatic knee OA with effusions or other physical signs of local inflammation.

• Intra-articular injections of hyaluronate can be helpful in some patients with knee OA who are unresponsive to, or intolerant of, repeated injections of intra-articular corticosteroids.

• Treatment with glucosamine and/or chondroitin sulphate may provide symptomatic benefit in patients with knee OA. If no response is apparent within 6 months, treatment should be discontinued. The evidence that these agents may also have structure-modifying effects in slowing the progression of articular cartilage loss remains inconclusive.

• The use of opioids and narcotic analgesics can be considered in exceptional circumstances for the treatment of severe, refractory pain where other pharmacological agents have been ineffective or are contraindicated. Non-pharmacological therapies should be continued in such patients and surgical treatments should be considered.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree