38

Orthopaedics in children

Antenatal and birth checks

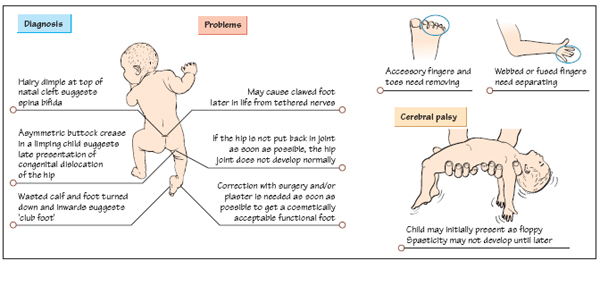

Screening, genetic counselling, the withdrawal of teratogenic drugs and appropriate nutrition have greatly reduced the incidence of spina bifida and other congenital abnormalities in babies in the developed world. However, at birth all babies are checked for the most common abnormalities, which are unstable hips, club foot and abnormalities of the fingers and toes such as webbing, extra or absent digits.

Developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH)

See Chapter 16.

Club foot (talipes equinovarus)

When the child is born, the foot is noted to be twisted down (equinus) and inwards (varus). This can either be a result of the position in the uterus (positional) or it can be congenital (failure of proper development of the calf and foot). If the problem is positional, then careful splinting will correct the problem. However, if the problem is anatomical (congenital), then surgical correction will be needed.

Webs, fusions and absent and accessory digits

Congenital abnormalities of the hand and foot can vary from slight webbing between two fingers or toes, through to complete absence of the limb. There may also be extra digits. Hands are very important in communication and not just for manipulation of tools, so cosmesis can be an important issue. Functionally in the hand, one of the most important needs is an opposable digit (a thumb). If this is absent then another digit may need to be rotated to take its place.

Artificial hands have proved very difficult to design because they require sensory feedback and exquisite control on grip pressure to come anywhere near the functionality of the normal hand.

Irritable hip

This is a common orthopaedic emergency because of the concern that serious pathology might be missed. The differentials are septic arthritis, Perthes’ disease and slipped upper femoral epiphysis (see Chapter 16).

Perthes’ disease and slipped upper femoral epiphysis

See Chapter 16.

Knock-knees and bow legs

Children may be referred to the clinic with either knock-knees (valgus) or bow legs (genu varus). The degree of deformity is best measured by getting the child to stand with either their feet together (in the case of bow legs), or with their knees together (in the case of knock-knees). The distance between the medial condyles of the femur (in the case of bow legs) or the medial malleoli of the ankles (in the case of knock-knees) can then be measured. Most of these cases are benign and correct with time. All that is required is a regular check that the deformity is indeed improving as the child grows, combined with reassurance to the parents.

Fractures

Fractures heal rapidly in children; even if there is some malunion, the bones have great potential for remodelling, so angulation that would be quite unacceptable in an adult can be left in a child to heal itself. Children’s bones are also quite flexible and may only break partially (a greenstick fracture). These tend to be stable and only need protecting for a couple of weeks while they heal. However, there are two issues that need careful consideration:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree