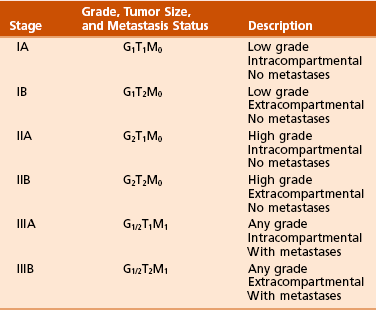

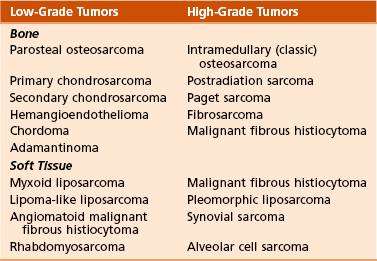

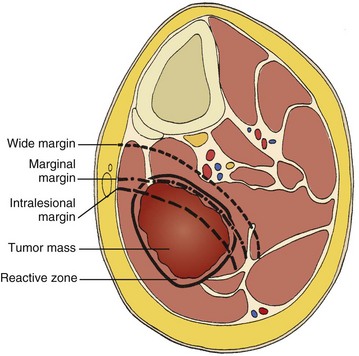

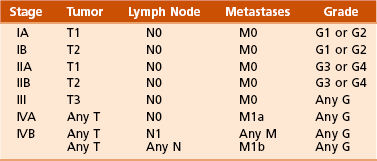

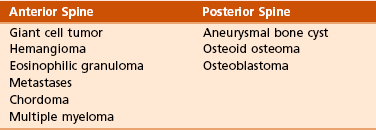

Chapter 9 A Enneking system: This staging system can be synthesized into six distinct stages (Table 9-1). B Variables of AJCC system: The most recent edition of the AJCC system has become more popular than Enneking’s system among medical oncologists and many orthopaedic oncologists. A working knowledge of both systems is necessary for examinations. To use this system, the clinician must know the grade, the size, the presence or absence of discontinuous tumor (skip metastases), and the absence or presence of systemic metastases. The various stages are listed in Table 9-2. The order of importance for the variables of the AJCC staging system is as follows: stage (takes into account all factors), presence of metastases, discontinuous tumor, grade, and size. Table 9-2 From American Joint Committee on Cancer: Bone. In Greene FL, et al, editor: AJCC cancer staging manual, New York, 2002, Springer-Verlag, pp 213-219. A Most grading systems are based on three grades: B The grade of the tumor is most strongly correlated with the potential for metastasis: 1. Grade I (low grade): less than 10% potential 2. Grade II (intermediate grade): 10% to 30% potential C Most malignant lesions are high grade (Enneking grade G2); low-grade malignant (Enneking grade G1) lesions are less common. Commonly graded lesions are shown in Table 9-3. A Within the bone compartment (intracompartmental, or T1) B Extending beyond the confines of the bone (extracompartmental, or T2) A Chest radiograph and CT scan of the chest are obtained to search for pulmonary lesions. B Technetium-labeled bone scan is obtained to exclude the presence of other bone lesions. A Clinical presentation: Most patients with bone tumors present with musculoskeletal pain. However, the most common presentation of a benign bone tumor in childhood is as an incidental finding. 1. Pain is typically deep-seated and may resemble a that of a toothache. 2. Pain may initially be intermittent and related to activity, a work injury, or a sporting injury. 3. Pain usually progresses in intensity and becomes constant. 4. Patients experience pain at night. 5. Pain progresses, and it is not relieved by nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or weaker narcotics (such as acetaminophen [Tylenol] with codeine). 6. Patients with a high-grade sarcoma present with a 1- to 3-month history of pain. 7. With low-grade tumors, such as chondrosarcoma, adamantinoma, and chordoma, there may be a long history of mild to moderate pain (6 to 24 months). B Physical examination: Patients with suspected bone tumors should be examined carefully. 1. Site is inspected for soft tissue masses, overlying skin changes, adenopathy, and general musculoskeletal condition. 2. When metastatic disease is suspected, the thyroid gland, abdomen, prostate, and breasts should be examined, as appropriate. C Imaging studies: Radiographs in two planes are the first imaging studies to be performed. When the clinician suspects malignancy but the radiographs are normal, selected studies may follow. 1. Technetium-labeled bone scan is an excellent modality to search for occult bone involvement. In patients with myeloma for whom scan results may be negative, a skeletal survey is more sensitive. 2. MRI is an excellent modality for screening the spine for occult metastases, myeloma, or lymphoma. 3. A chest radiograph should be obtained for patients of any age when the clinician suspects a malignant lesion. 4. The radiographs must be carefully inspected to formulate a working diagnosis. The working diagnosis then guides the clinician during further evaluation and treatment. Formulation of the differential diagnosis is based on several clinical and radiographic parameters: Table 9-5 Most Common Musculoskeletal Tumors Courtesy of Luke S. Choi, MD, Resident, Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, University of Virginia. Table 9-6 Courtesy of Luke S. Choi, MD, Resident, Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, University of Virginia. D Laboratory studies: Results of blood tests are often nonspecific. A set of routine studies should be obtained when the diagnosis is not obvious. Certain studies are appropriate for younger patients (up to age 40) and others for older patients (40 to 80 years; Box 9-1). E Biopsy: Biopsy is generally performed after complete evaluation of the patient. It is of great benefit to both the pathologist and the surgeon to have a narrow working diagnosis because it allows accurate interpretation of the frozen-section analysis, and definitive treatment of some lesions can be based on the frozen section. Clinicians must follow several surgical principles: 1. The orientation and location of the biopsy tract are critical. If the lesion proves to be malignant, the entire biopsy tract must be removed with the underlying lesion. Transverse incisions should be avoided. 2. The surgeon must maintain meticulous hemostasis to prevent hematoma formation and subcutaneous hemorrhage. When possible, biopsy incisions are made through muscles so that the muscle layer can be closed tightly. Neurovascular structures should be avoided. Tourniquets are used to obtain tissue in a bloodless field and then are released so that bleeding points can be controlled. Avitene, Gelfoam, and Thrombostat sprays are used as necessary. If hemostasis cannot be achieved, a small drain should be placed at the corner of the wound to prevent hematoma formation. A compression dressing is routinely used on the extremities. 3. A frozen-section analysis is performed on all biopsy samples to ensure that adequate diagnostic tissue is obtained. Before biopsy, the surgeon should review the radiographs with the pathologist to plan the biopsy site. When possible, the soft tissue component rather than the bony component should be sampled. 4. All biopsy samples should be submitted for bacteriologic analysis if the frozen section does not reveal a neoplasm. Antibiotics should not be delivered until the cultures are obtained. 5. Needle biopsy is an excellent method for achieving a tissue diagnosis and providing minimum tissue disruption. Careful correlation of the small tissue sample with the radiographs often yields the correct diagnosis. When the nature of the lesion is obvious on the basis of the radiographic features and when adequate tissue can be obtained with a needle, the needle biopsy technique is safe to use. The pathologist must be experienced and comfortable with the small sample of tissue. When the diagnoses of needle biopsy and imaging studies are not concordant, an open biopsy should be performed to establish the diagnosis. Open biopsy is often necessary with low-grade tumors and when the needle biopsy does not provide a definitive diagnosis. Immunostains are helpful in diagnosis (Table 9-7). Table 9-7 Courtesy of Luke S. Choi, MD, Resident, Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, University of Virginia. A Surgical procedures: The goal of the treatment of malignant bone tumors is to remove the lesion with minimal risk of local recurrence. 1. Limb salvage is performed when two essential criteria are met: 2. Surgical margins are graded according to the system of the Musculoskeletal Tumor Society (Figure 9-2). Several bone and soft tissue neoplasms have been associated with tumor suppressor genes or specific genetic defects. For osteosarcoma, the associations are the retinoblastoma tumor suppressor gene. For Ewing tumor, there is a balanced translocation of chromosomes 11 and 22. There is a gene fusion product from this balanced translocation: EWS-FLI1 (Table 9-8). Table 9-8 Common Tumor-Associated Genetic Translocations Courtesy of Luke S. Choi, MD, Fellow, Orthopaedic Sports Medicine, Massachusetts General Hospital. Soft tissue tumors are common. They may appear as small lumps or large masses. A Classification: Soft tissue tumors can be broadly classified as benign or malignant (sarcoma) or characterized by reactive tumor-like conditions (Box 9-2). Lesions are classified according to the direction of differentiation of the lesion: the tumor tends to produce collagen (fibrous lesion), fat, or cartilage. 1. Benign soft tissue tumors: These tumors may occur in all age groups. The biologic behavior of these lesions varies from asymptomatic and self-limiting to growing and symptomatic. On occasion, benign lesions grow rapidly and invade adjacent tissues. 2. Malignant soft tissue tumors (sarcomas): Sarcomas are rare tumors of mesenchymal origin. In the United States, there are approximately 9000 new cases of soft tissue sarcoma each year. B Diagnosis: The evaluation of patients with soft tissue tumors must be systematic to avoid errors. 1. Unplanned removal of a soft tissue sarcoma is the most common error. 2. Delay in diagnosis may also occur if the clinician does not recognize that the lesion is malignant. 3. Patients who have a new soft tissue mass or one that is growing or causing pain should undergo MRI. 4. The MRI scan should be carefully reviewed with a radiologist to characterize the nature of the mass. If it can be determined that the lesion is a benign process such as a lipoma, ganglionic cyst, or muscle tear, then it is classified as a determinate lesion, and treatment can be planned without a biopsy. In contrast, if the exact nature of a lesion cannot be determined, the lesion is classified as indeterminate, and either a needle or open biopsy is necessary to determine the exact diagnosis. Then treatment can be planned. 5. Excisional biopsy should not be performed when the clinician does not know the origin of a soft tissue tumor. C Metastasis: Most soft tissue sarcomas metastasize to the lung. A Calcifying aponeurotic fibroma 1. Manifests as a slow-growing, painless mass in the hands and feet in children and young adults 3 to 30 years of age. 2. Radiographs may reveal a faint mass with stippling. 3. Histologic examination reveals a fibrous tumor with centrally located areas of calcification and cartilage formation. 4. After local excision, the tumor often recurs (in up to 50% of cases); however, the condition appears to resolve with maturity. 1. Palmar (Dupuytren) and plantar (Ledderhose) fibromatosis: These disorders consist of firm nodules of fibroblasts and collagen that develop in the palmar and plantar fascia. The nodules and fascia become hypertrophic, producing contractures. 2. Extraabdominal desmoid tumor 1. A common reactive lesion that manifests as a painful, rapidly enlarging mass in a young person (15 to 35 years of age). 2. Half of these lesions occur in the upper extremity. 3. Short, irregular bundles and fascicles; a dense reticulum network; and only small amounts of mature collagen characterize the lesion histologically. Mitotic figures are common, but atypical mitoses are not a feature. 4. Treatment consists of excision with a marginal line of resection. D Malignant fibrous soft tissue tumors: Malignant fibrous histiocytoma and fibrosarcoma are the two malignant fibrous lesions. E Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans 1. Rare, nodular, cutaneous tumor that occurs in early to middle adulthood 2. Low grade, with a tendency to recur locally, but it only rarely metastasizes (often after repeated local recurrence) 3. In 40% of the cases, it occurs on the upper or lower extremities. The tumor grows slowly but progressively. 4. The central portion of the nodules shows uniform fibroblasts arranged in a storiform pattern around an inconspicuous vasculature. 5. Wide-margin surgical resection is the best form of treatment. A Lipomas: common benign tumors of mature fat 1. Occur in a subcutaneous, intramuscular, or intermuscular location 2. History of a mass is long, but sometimes the mass was only recently discovered. 4. Radiographs may show a radiolucent lesion in the soft tissues if the lipoma is deep within the muscle or between the muscle and bone. 5. CT scan or MRI shows a well-demarcated lesion with the same signal characteristics as those of mature fat on all sequences. On fat suppression sequences, the lipoma has a uniformly low signal. If the patient experiences no symptoms and the radiographic features are diagnostic of lipoma, no treatment is necessary. 6. If the mass is growing or causing symptoms, excision with a marginal line of resection or an intralesional margin is all that is necessary. 7. Local recurrence is uncommon. 1. Type of sarcoma; direction of differentiation is toward fatty tissue 2. Heterogeneous group of tumors, having in common the presence of lipoblasts (signet ring–shaped cells) in the tissue 3. Liposarcomas virtually never occur in the subcutaneous tissues. 4. They are classified into the following types: 5. Liposarcomas metastasize according to the grade of the lesion: A Neurilemoma (benign schwannoma) 2. Occurs in young to middle-aged adults (20 to 50 years of age) 3. Patients have no symptoms except for the presence of the mass. 4. Tumor grows slowly and may wax and wane in size (cystic changes). 5. MRI studies may demonstrate an eccentric mass arising from a peripheral nerve, or they may show only an indeterminate soft tissue mass (low signal on T1-weighted images and high signal on T2-weighted images). 6. Histologically, the lesion is composed of Antoni A and B areas. 1. Solitary or multiple (neurofibromatosis) 2. Superficial, slow-growing, and painless 3. When they involve a major nerve, they may expand it in a fusiform manner. 4. Histologic study shows interlacing bundles of elongated cells with wavy, dark-staining nuclei. 5. Cells are associated with wirelike strands of collagen. 6. Small to moderate amounts of mucoid material separate the cells and collagen C Neurofibromatosis (von Recklinghausen disease) 1. Autosomal dominant trait (both peripheral and central forms) 2. Café au lait spots (smooth) and Lisch nodules (melanocytic hamartomas in the iris) 3. Variable skeletal abnormalities (metaphyseal fibrous defect [nonossifying fibroma], scoliosis, and long-bone bowing) 4. Malignant changes occur in 5% to 30% of affected patients. 5. Pain and an enlarging soft tissue mass may herald conversion to a sarcoma.

Orthopaedic Pathology

section 1 Introduction

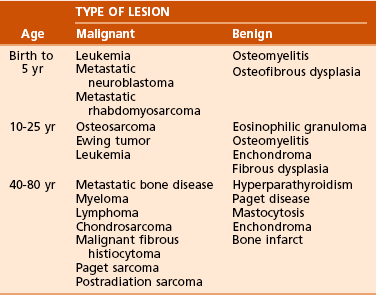

Age of the patient: Knowledge of common diseases in defined age groups is the first step. Certain diseases are uncommon in particular age groups (Table 9-4).

Age of the patient: Knowledge of common diseases in defined age groups is the first step. Certain diseases are uncommon in particular age groups (Table 9-4).

Number of bone lesions: Is the process monostotic or polyostotic? If there are multiple destructive lesions in middle-aged and older patients (ages 40 to 80 years), the most likely diagnosis is metastatic bone disease, multiple myeloma, or lymphoma. In young patients (ages 15 to 40 years), multiple lytic and oval lesions in the same extremity are probably vascular tumors (hemangioendothelioma). In children younger than 5 years, multiple destructive lesions may represent metastatic disease such as neuroblastoma or Wilms tumor. Histiocytosis X (Langerhans cell histiocytosis [LCH]) may also lead to multiple lesions in the young patient. Fibrous dysplasia and Paget disease may manifest with multiple lesions in all age groups.

Number of bone lesions: Is the process monostotic or polyostotic? If there are multiple destructive lesions in middle-aged and older patients (ages 40 to 80 years), the most likely diagnosis is metastatic bone disease, multiple myeloma, or lymphoma. In young patients (ages 15 to 40 years), multiple lytic and oval lesions in the same extremity are probably vascular tumors (hemangioendothelioma). In children younger than 5 years, multiple destructive lesions may represent metastatic disease such as neuroblastoma or Wilms tumor. Histiocytosis X (Langerhans cell histiocytosis [LCH]) may also lead to multiple lesions in the young patient. Fibrous dysplasia and Paget disease may manifest with multiple lesions in all age groups.

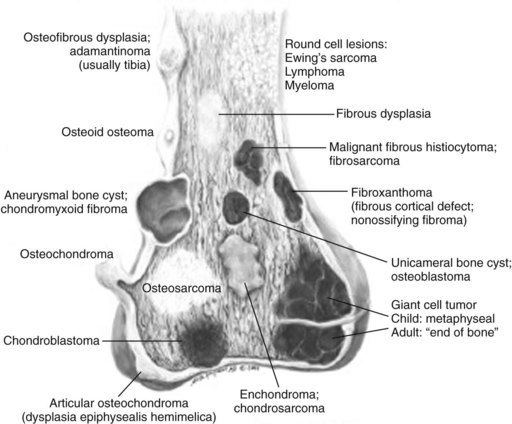

Anatomic location within bone: Certain lesions have a predilection for occurring within a certain bone or a particular part of the bone (Figure 9-1; Table 9-5).

Anatomic location within bone: Certain lesions have a predilection for occurring within a certain bone or a particular part of the bone (Figure 9-1; Table 9-5).

![]()

Tumor Type

Tumor Name

Soft tissue tumor (children)

Hemangioma

Soft tissue tumor (adults)

Lipoma

Malignant soft tissue tumor (children)

Rhabdomyosarcoma

Malignant soft tissue tumor (adults)

Malignant fibrous histiocytoma

Primary benign bone tumor

Osteochondroma

Primary malignant bone tumor

Osteosarcoma

Secondary benign lesion

Aneurysmal bone cyst

Secondary malignancies

Malignant fibrous histiocytoma

Osteosarcoma

Fibrosarcoma

Phalangeal tumor

Enchondroma

Sarcoma of the hand and wrist

Epithelioid sarcoma

Sarcoma of the foot and ankle

Synovial sarcoma

Typical neoplasms of whole bone:

Typical neoplasms of whole bone:

Tibia: adamantinoma, osteofibrous dysplasia

Tibia: adamantinoma, osteofibrous dysplasia

Posterior cortex distal femur: parosteal osteosarcoma, periosteal desmoid (also known as cortical desmoid, avulsive cortical irregularity)

Posterior cortex distal femur: parosteal osteosarcoma, periosteal desmoid (also known as cortical desmoid, avulsive cortical irregularity)

Typical neoplasms of part of bone (Table 9-6):

Typical neoplasms of part of bone (Table 9-6):

Epiphysis: giant cell tumor, chondroblastoma, aneurysmal bone cyst, osteomyelitis (tuberculosis, fungus)

Epiphysis: giant cell tumor, chondroblastoma, aneurysmal bone cyst, osteomyelitis (tuberculosis, fungus)

Giant cell tumor typically begins in the metaphysis and extends through the epiphysis to lie just below the cartilage.

Giant cell tumor typically begins in the metaphysis and extends through the epiphysis to lie just below the cartilage.

Metaphysis: metaphyseal fibrous defect (nonossifying fibroma), aneurysmal bone cyst, giant cell tumor, osteosarcoma

Metaphysis: metaphyseal fibrous defect (nonossifying fibroma), aneurysmal bone cyst, giant cell tumor, osteosarcoma

Diaphysis: Ewing sarcoma, fibrous dysplasia, eosinophilic granuloma (histiocytosis), multiple myeloma

Diaphysis: Ewing sarcoma, fibrous dysplasia, eosinophilic granuloma (histiocytosis), multiple myeloma

Tumor

Immunostain

Langerhans cell histiocytosis

S100, +CD1A

Lymphoma

+CD20

Ewing sarcoma

+CD99

Chordoma

Keratin, S100

Myeloma

+CD138

Adamantinoma

Keratin

Local control of the lesion must be at least equal to that of amputation surgery.

Local control of the lesion must be at least equal to that of amputation surgery.

The limb that has been saved must be functional. A wide-margin surgical resection (excising a cuff of normal tissue around the tumor) is the operative goal.

The limb that has been saved must be functional. A wide-margin surgical resection (excising a cuff of normal tissue around the tumor) is the operative goal.

Intralesional margin: The plane of dissection goes directly through the tumor. When the surgery involves malignant mesenchymal tumors, an intralesional margin results in 100% local recurrence.

Intralesional margin: The plane of dissection goes directly through the tumor. When the surgery involves malignant mesenchymal tumors, an intralesional margin results in 100% local recurrence.

Marginal margin: A marginal line of resection goes through the reactive zone of the tumor; the reactive zone contains inflammatory cells, edema, fibrous tissue, and satellites of tumor cells. When malignant mesenchymal tumors are resected, a plane of dissection through the reactive zone probably results in a local recurrence rate of 25% to 50%. A marginal margin may be safe and effective if the response to preoperative chemotherapy has been excellent (95% to 100% tumor necrosis).

Marginal margin: A marginal line of resection goes through the reactive zone of the tumor; the reactive zone contains inflammatory cells, edema, fibrous tissue, and satellites of tumor cells. When malignant mesenchymal tumors are resected, a plane of dissection through the reactive zone probably results in a local recurrence rate of 25% to 50%. A marginal margin may be safe and effective if the response to preoperative chemotherapy has been excellent (95% to 100% tumor necrosis).

Wide margin: A wide line of surgical resection is accomplished when the entire tumor is removed with a cuff of normal tissue. The local recurrence rate drops below 10% when such a surgical margin is achieved.

Wide margin: A wide line of surgical resection is accomplished when the entire tumor is removed with a cuff of normal tissue. The local recurrence rate drops below 10% when such a surgical margin is achieved.

Radical margin: A radical margin is achieved when the entire tumor and its compartment (all surrounding muscles, ligaments, and connective tissues) are removed.

Radical margin: A radical margin is achieved when the entire tumor and its compartment (all surrounding muscles, ligaments, and connective tissues) are removed.

Multiagent chemotherapy has a significant effect on both the efficacy of limb salvage and disease-free survival for osteogenic sarcoma and Ewing tumor.

Multiagent chemotherapy has a significant effect on both the efficacy of limb salvage and disease-free survival for osteogenic sarcoma and Ewing tumor.

The common mechanism of action of drugs is the induction of programmed cell death (apoptosis).

The common mechanism of action of drugs is the induction of programmed cell death (apoptosis).

Most protocols entail preoperative regimens (neoadjuvant chemotherapy) for 8 to 24 weeks. The tumor is then restaged and, if appropriate, limb salvage is performed.

Most protocols entail preoperative regimens (neoadjuvant chemotherapy) for 8 to 24 weeks. The tumor is then restaged and, if appropriate, limb salvage is performed.

Patients undergo maintenance chemotherapy for 6 to 12 months.

Patients undergo maintenance chemotherapy for 6 to 12 months.

Patients with localized osteosarcoma or Ewing tumor have up to a 60% to 70% chance for long-term disease-free survival with the combination of multiagent chemotherapy and surgery.

Patients with localized osteosarcoma or Ewing tumor have up to a 60% to 70% chance for long-term disease-free survival with the combination of multiagent chemotherapy and surgery.

The role of chemotherapy for soft tissue sarcoma remains more controversial.

The role of chemotherapy for soft tissue sarcoma remains more controversial.

External beam irradiation is used in the following scenarios:

External beam irradiation is used in the following scenarios:

For local control of Ewing tumor, lymphoma, myeloma, and metastatic bone disease

For local control of Ewing tumor, lymphoma, myeloma, and metastatic bone disease

As an adjunct in the treatment of soft tissue sarcomas, in which it is used in combination with surgery.

As an adjunct in the treatment of soft tissue sarcomas, in which it is used in combination with surgery.

For their mechanism of action, which is the production of free radicals and direct genetic damage. There are several complications of radiation therapy:

For their mechanism of action, which is the production of free radicals and direct genetic damage. There are several complications of radiation therapy:

Postirradiation sarcoma: This is a devastating complication in which a spindle sarcoma occurs within the field of irradiation for a previous malignancy (e.g., Ewing tumor, breast cancer, Hodgkin disease). The histologic features are usually those of an osteosarcoma, a fibrosarcoma, or a malignant fibrous histiocytoma. Postirradiation sarcomas are probably more frequent in patients who undergo intensive chemotherapy (especially with alkylating agents) and irradiation.

Postirradiation sarcoma: This is a devastating complication in which a spindle sarcoma occurs within the field of irradiation for a previous malignancy (e.g., Ewing tumor, breast cancer, Hodgkin disease). The histologic features are usually those of an osteosarcoma, a fibrosarcoma, or a malignant fibrous histiocytoma. Postirradiation sarcomas are probably more frequent in patients who undergo intensive chemotherapy (especially with alkylating agents) and irradiation.

Late stress fractures: These also may occur in weight-bearing bones to which high-dose irradiation has been applied. The subtrochanteric region and the diaphysis of the femur are common sites.

Late stress fractures: These also may occur in weight-bearing bones to which high-dose irradiation has been applied. The subtrochanteric region and the diaphysis of the femur are common sites.

![]()

Tumor Type

Genetic Translocation

Myxoid liposarcoma

t(12;16)

Ewing sarcoma

t(11;22)

Synovial sarcoma

t(X;18)

Myxoid chondrosarcoma

t(9;22)

Rhabdomyosarcoma

t(1;13) or t(2;13)

section 2 Soft Tissue Tumors

Diagnosis: Patients often experience an enlarging painless or painful soft tissue mass, which is the most common reason for seeking medical attention.

Diagnosis: Patients often experience an enlarging painless or painful soft tissue mass, which is the most common reason for seeking medical attention.

Most sarcomas are large (>5 cm), deep, and firm.

Most sarcomas are large (>5 cm), deep, and firm.

In some instances, they are small and may be present for a long time before they are recognized as tumors (synovial sarcoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, epithelioid sarcoma, and clear cell sarcoma).

In some instances, they are small and may be present for a long time before they are recognized as tumors (synovial sarcoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, epithelioid sarcoma, and clear cell sarcoma).

Initial radiographic evaluation begins with radiographs in two planes.

Initial radiographic evaluation begins with radiographs in two planes.

MRI is the best imaging modality for defining the anatomy and helping characterize the lesion. When a mass is judged to be indeterminate, an open incisional or needle biopsy is performed. A definitive histologic diagnosis must be established before treatment is planned.

MRI is the best imaging modality for defining the anatomy and helping characterize the lesion. When a mass is judged to be indeterminate, an open incisional or needle biopsy is performed. A definitive histologic diagnosis must be established before treatment is planned.

CT scan of the chest is required in order to evaluate for metastasis. CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis is obtained for liposarcoma because of synchronous retroperitoneal liposarcoma.

CT scan of the chest is required in order to evaluate for metastasis. CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis is obtained for liposarcoma because of synchronous retroperitoneal liposarcoma.

Treatment: Radiation therapy is an important adjunct to surgery in the treatment of soft tissue sarcomas.

Treatment: Radiation therapy is an important adjunct to surgery in the treatment of soft tissue sarcomas.

Ionizing radiation can be delivered preoperatively, perioperatively with brachytherapy after loading tubes, or postoperatively.

Ionizing radiation can be delivered preoperatively, perioperatively with brachytherapy after loading tubes, or postoperatively.

Treatment regimens are often designed to use combinations of the three types of preoperative, postoperative, and external beam irradiation. Poor prognostic factors include the presence of metastases, high grade, size greater than 5 cm, and location below the deep fascia.

Treatment regimens are often designed to use combinations of the three types of preoperative, postoperative, and external beam irradiation. Poor prognostic factors include the presence of metastases, high grade, size greater than 5 cm, and location below the deep fascia.

Residual tumor may exist at the site of the operative wound, and repeat excision for all patients with an unplanned removal should be performed.

Residual tumor may exist at the site of the operative wound, and repeat excision for all patients with an unplanned removal should be performed.

Most locally invasive of all benign soft tissue tumors.

Most locally invasive of all benign soft tissue tumors.

Commonly occurs in adolescents and young adults.

Commonly occurs in adolescents and young adults.

Patients with Gardner syndrome (familial adenomatous polyposis) have colonic polyps and a 10,000-fold increased risk of developing desmoid tumors.

Patients with Gardner syndrome (familial adenomatous polyposis) have colonic polyps and a 10,000-fold increased risk of developing desmoid tumors.

On palpation, the tumor has a distinctive “rock-hard” character.

On palpation, the tumor has a distinctive “rock-hard” character.

Multiple lesions may be present in the same extremity (10% to 25%).

Multiple lesions may be present in the same extremity (10% to 25%).

Histologically, the tumor consists of well-differentiated fibroblasts and abundant collagen. The lesion infiltrates adjacent tissues. Immunohistochemistry study reveals positivity for estrogen receptor β, and inhibitors have been used for treatment.

Histologically, the tumor consists of well-differentiated fibroblasts and abundant collagen. The lesion infiltrates adjacent tissues. Immunohistochemistry study reveals positivity for estrogen receptor β, and inhibitors have been used for treatment.

Surgical treatment is aimed at resecting the tumor with a wide margin.

Surgical treatment is aimed at resecting the tumor with a wide margin.

Radiotherapy has been used as an adjunctive treatment to prevent recurrence and progression.

Radiotherapy has been used as an adjunctive treatment to prevent recurrence and progression.

Behavior of the tumor is capricious: Recurrent nodules may remain dormant for years or grow rapidly for some time and then stop growing.

Behavior of the tumor is capricious: Recurrent nodules may remain dormant for years or grow rapidly for some time and then stop growing.

Similar clinical and radiographic manifestations; treatment methods are similar

Similar clinical and radiographic manifestations; treatment methods are similar

Patients are generally between the ages of 30 and 80 years.

Patients are generally between the ages of 30 and 80 years.

Most common manifestation is an enlarging, generally painless mass.

Most common manifestation is an enlarging, generally painless mass.

MRI often shows a deep-seated, inhomogeneous mass that has a low signal on T1-weighted images and a high signal on T2-weighted images. The two lesions may be similar histologically, but there are distinctive features:

MRI often shows a deep-seated, inhomogeneous mass that has a low signal on T1-weighted images and a high signal on T2-weighted images. The two lesions may be similar histologically, but there are distinctive features:

Malignant fibrous histiocytoma: The spindle and histiocytic cells are arranged in a storiform (cartwheel) pattern. Short fascicles of cells and fibrous tissue appear to radiate about a common center around slitlike vessels. Chronic inflammatory cells may also be present.

Malignant fibrous histiocytoma: The spindle and histiocytic cells are arranged in a storiform (cartwheel) pattern. Short fascicles of cells and fibrous tissue appear to radiate about a common center around slitlike vessels. Chronic inflammatory cells may also be present.

Fibrosarcoma: There is a fasciculated growth pattern, with fusiform or spindle-shaped cells, scanty cytoplasm, and indistinct borders, and the cells are separated by interwoven collagen fibers. In some cases, the tissue is organized into a herringbone pattern, which consists of intersecting fascicles in which the nuclei in one fascicle are viewed transversely but in an adjacent fascicle are viewed longitudinally.

Fibrosarcoma: There is a fasciculated growth pattern, with fusiform or spindle-shaped cells, scanty cytoplasm, and indistinct borders, and the cells are separated by interwoven collagen fibers. In some cases, the tissue is organized into a herringbone pattern, which consists of intersecting fascicles in which the nuclei in one fascicle are viewed transversely but in an adjacent fascicle are viewed longitudinally.

Treatment is by wide-margin local excision. Radiation therapy is employed in many cases when the size of the tumor exceeds 5 cm.

Treatment is by wide-margin local excision. Radiation therapy is employed in many cases when the size of the tumor exceeds 5 cm.

A common scenario is to deliver radiation preoperatively (5000 cGy), followed by resection of the lesion. A final radiation boost (1400 to 2000 cGy) is then administered postoperatively or with brachytherapy afterloading tubes if the margins are very close or positive.

A common scenario is to deliver radiation preoperatively (5000 cGy), followed by resection of the lesion. A final radiation boost (1400 to 2000 cGy) is then administered postoperatively or with brachytherapy afterloading tubes if the margins are very close or positive.

Postoperative external beam irradiation (6300 to 6600 cGy) yields equal local control rates, with a lower postoperative wound complication rate but a higher incidence of postoperative fibrosis.

Postoperative external beam irradiation (6300 to 6600 cGy) yields equal local control rates, with a lower postoperative wound complication rate but a higher incidence of postoperative fibrosis.

Commonly occurs in men (45 to 65 years of age)

Commonly occurs in men (45 to 65 years of age)

Manifests as a solitary, painless, growing, firm nodule

Manifests as a solitary, painless, growing, firm nodule

Histologically characterized by a mixture of mature fat cells and spindle cells. There is a mucoid matrix with a varying number of birefringent collagen fibers.

Histologically characterized by a mixture of mature fat cells and spindle cells. There is a mucoid matrix with a varying number of birefringent collagen fibers.

Occurs in middle-aged patients

Occurs in middle-aged patients

Manifests as a slow-growing mass

Manifests as a slow-growing mass

Histologically characterized by lipocytes; spindle cells; and scattered, bizarre giant cells

Histologically characterized by lipocytes; spindle cells; and scattered, bizarre giant cells

May be confused with different types of liposarcoma

May be confused with different types of liposarcoma

Well-differentiated liposarcoma (low grade)

Well-differentiated liposarcoma (low grade)

Myxoid liposarcoma (intermediate grade)

Myxoid liposarcoma (intermediate grade)

Round-cell liposarcoma (high grade)

Round-cell liposarcoma (high grade)

Compact spindle cells usually having twisted nuclei; indistinct cytoplasm; and occasionally clear, intranuclear vacuoles

Compact spindle cells usually having twisted nuclei; indistinct cytoplasm; and occasionally clear, intranuclear vacuoles

There may be nuclear palisading, whorling of cells, and Verocay bodies.

There may be nuclear palisading, whorling of cells, and Verocay bodies.

When the lesion is predominantly cellular (Antoni A), the tumor may be confused with a sarcoma.

When the lesion is predominantly cellular (Antoni A), the tumor may be confused with a sarcoma.

Treatment: removing the eccentric mass while leaving the nerve intact

Treatment: removing the eccentric mass while leaving the nerve intact

Orthopaedic Pathology