Operative Management of Unicameral Bone Cyst, Aneurysmal Bone Cyst, and Nonossifying Fibroma

Alexandre Arkader

UNICAMERAL BONE CYST

DEFINITION

Unicameral bone cyst (UBC) or simple bone cyst is a benign, active or latent, solitary fluid-filled cystic lesion that usually involves the metaphysis of long bones.

PATHOGENESIS

The cause is unknown; theories range from a reactive or developmental process to a true neoplasm. The most likely cause is perhaps an obstruction to the drainage of interstitial fluid, leading to the accumulation of fluid under pressure.

Few isolated reports have shown cytogenetic abnormalities including the presence of translocation t(16;20)(p11.2;q13) and t(7;12)(q21;q24.3) and TP53 mutations in recurrent UBCs.

UBCs are characterized by a fluid-filled cyst lined with a thin fibrous membrane without endothelial cell lining. However, owing to the high incidence of associated fractures, several nonspecific changes may be seen, such as hemorrhage, hemosiderin deposits, granulation tissue, new bone formation, and others.

NATURAL HISTORY

Active cysts are generally located near the growth plate and are usually asymptomatic. Approximately 85% of these cysts are diagnosed at the time of a pathologic fracture.

Inactive or latent cysts tend to “migrate” away from the growth plate as longitudinal growth occurs and populate the midshaft or diaphyseal region.

UBCs may regress spontaneously after skeletal maturity.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

UBCs are usually asymptomatic; the usual presentation is with a pathologic fracture following a minor trauma.

UBC is more often in boys (3:1), especially during the first two decades. The most common locations are the proximal humerus and the femur, accounting for 50% to 70% of the lesions. Calcaneal UBCs tend to occur in a slightly older group.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Plain radiographs typically demonstrate a well-defined, centrally located, radiolucent lesion that may be associated with varying degrees of cortical thinning and mild expansion (FIG 1).

When UBCs are associated with bone expansion, it generally does not exceed the width of the nearest growth plate.

When a pathologic fracture occurs, there may be periosteal reaction, and occasionally, the typical “fallen leaf” sign is visualized (piece of fractured cortex “floating” inside the cavity). Most pathologic fractures are minimally displaced and stable.

Computed tomography (CT) may be useful to characterize lesions that are of difficult visualization on plain films (eg, spine, pelvis) and to rule out fractures (nondisplaced or minimally displaced).

Noninvasive quantitative CT has been applied to evaluation of the risk of pathologic fractures through bone cyst and other benign bone lesions.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is usually only needed for differential diagnosis of atypical UBCs.

Although the appearance may vary, they present as low to intermediate signals on T1-weighted images and bright and homogeneous signals on T2-weighted images.

FIG 1 • Lateral radiograph of the foot of a 12-year-old boy demonstrates a well-circumscribed, lucent lesion, consistent with unicameral bone cyst. |

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Aneurysmal bone cyst (ABC)

Nonossifying fibroma (NOF)

Fibrous dysplasia (differential with latent/diaphyseal UBC)

Brown tumor of hyperparathyroidism (usually presents with osteopenia and subcortical resorption)

Osteomyelitis (commonly shows periosteal reaction)

For calcaneus lesions, the differential also includes chondroblastoma and giant cell tumor.

NONOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

Lesions with typical radiographic appearance involving non-weight-bearing bones, especially in the absence of significant cortical thinning, can be followed with serial radiographs.

Small lesions (ie, those that involve less than one-third to half of the bone width) in weight-bearing bones that have low risk for fracture can also be observed.

Following pathologic fracture, up to 15% of UBCs may spontaneously heal, and therefore an attempt for conservative treatment should be made. Exceptions include large lesions and unstable or displaced fractures of lower extremities, especially in older children.

ANEURYSMAL BONE CYST

DEFINITION

ABC is a benign, active, and sometimes locally aggressive, solitary, expansile blood-filled cystic lesion, eccentric in location, most commonly seen in the metaphyseal region of long bones or posterior elements of the spine.

PATHOGENESIS

The neoplastic basis of primary ABCs has been, at least in part, demonstrated by the chromosomal translocation t(16;17)(q22;p13) that places the ubiquitin protease (UBP) USP6 gene under the regulatory influence of the highly active osteoblast cadherin 11 gene (CDH11), which is strongly expressed in bones. Abnormalities of the short arm of chromosome 17 appear to be recurrent.

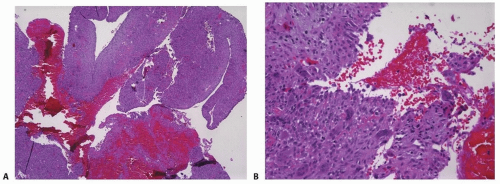

The lesion contains blood-filled cystic spaces that are not lined with vascular endothelium, divided by fibrous septa containing giant cells and immature bone (FIG 2).

NATURAL HISTORY

ABC can present as an active or locally aggressive lesion that tends to continue to grow and warrants intervention.

They may also occur in association with other lesions such as giant cell tumor, osteoblastoma, chondroblastoma, or fibrous dysplasia.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

ABCs often present with pain. Sometimes, swelling or a “mass” can be present.

Pathologic fracture is not as prevalent as in UBC but it may occur following minor trauma.

The most common locations are the metaphysis of long bones, particularly the femur and tibia, and the posterior elements of the spine.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Plain radiographs show an eccentric, multilobulated, expansile (often expanding beyond the width of the nearest growth plate), radiolucent lesion with a narrow zone of transition.

Cortical thinning, disruption, and periosteal reaction are common.

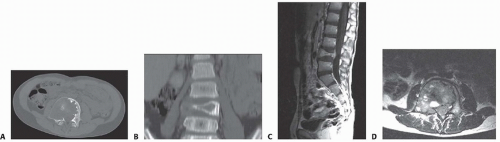

CT is helpful, for better characterization and treatment planning of axial lesions (FIG 3A,B).

CT demonstrates the typical ridges in the interior of the cyst.

Soft tissue extension can be appreciated, but there is no true soft tissue mass.

MRI is useful to confirm the lobulated nature of the lesion and the cystic cavities filled with fluid; fluid levels on T2-weighted signal are characteristic but not pathognomonic (FIG 3C,D).

There is variable signal intensity in both T1- and T2-weighted images due to the nature of the cyst contents (fresh blood, mixed with degraded blood products).

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

UBC

NOF

Giant cell tumor

Osteoblastoma

Telangiectatic osteogenic sarcoma

NONOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

There is little place for conservative treatment of ABCs. At least an incisional biopsy for diagnosis confirmation is recommended.

For small, asymptomatic lesions located in non-weight-bearing bones, observation can be indicated.

For lesions that are of difficult access/approach, serial embolization or sclerotherapy is another option.

NONOSSIFYING FIBROMA

DEFINITION

NOF is a benign latent, cystic, eccentric, and cortical-based lesion that is most often found incidentally in the metaphyseal region of long bones. NOFs are the most common benign fibrous lesions, and it is estimated that up to 20% of all children have an NOF or the smaller counterpart, fibrous cortical defect. These lesions can be multicentric or synchronous.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree