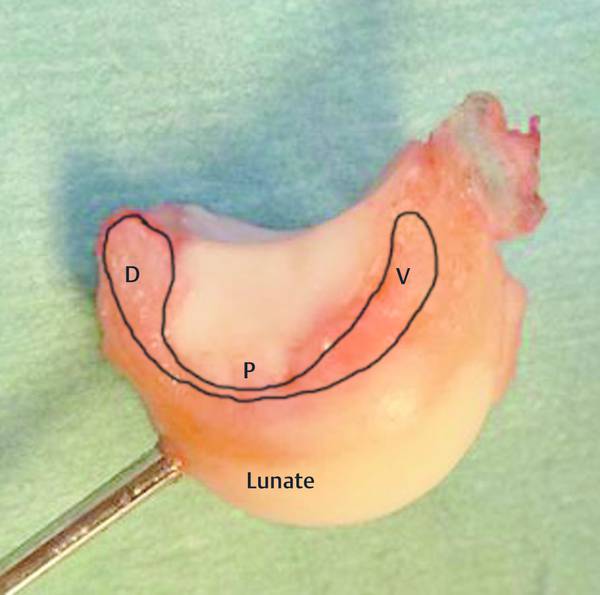

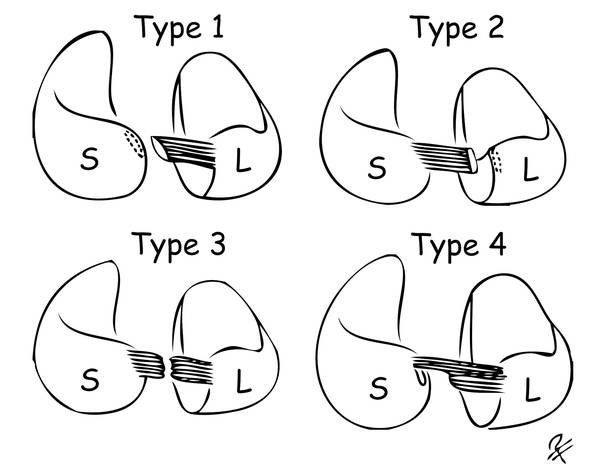

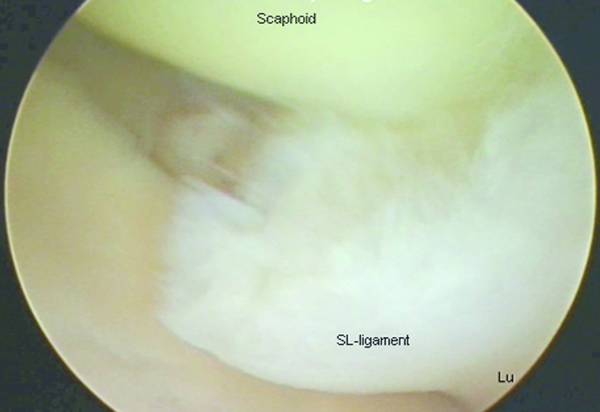

The scapholunate ligament (SLL) has three structurally distinct parts: dorsal, proximal-membranous, and palmar (▶ Fig. 17.1). Scapholunate ligament injury is common among young individuals, particularly males, and the dominant side is predominantly affected. The injury is often the consequence of a fall from a height or a motorcycle accident. In dorsal extension and ulnar deviation of the wrist at the moment of injury and impact, the unconstrained scaphoid will be pulled away from the lunate until the different parts of the SLL rupture under tension. This most often starts palmarly and progresses dorsally, until the last fibers of the dorsal SLL rupture, completing the total SL dissociation (SLD). The dorsal SLL, which is the strongest (260 N), is the primary stabilizer of the scapholunate joint.1 The membranous proximal part of the SLL (63 N) does not provide any significant restraint, but the palmar aspect (118 N), although thin, does assist the rotational stability. Fig. 17.1 The scapholunate ligament has three structurally distinct parts: dorsal (D), which is the most important and strongest part; proximal–membranous (P); and volar–palmar (V). SLL rupture is the most common cause of carpal instability and secondary wrist dysfunction, but the potential adverse effects of SLL injuries are often underestimated and these injuries most often remain untreated or inadequately managed. In addition to isolated SLL ruptures and perilunate injuries, we know from some recent studies that one can also see associated SLL injuries in patients with distal radius fractures (reported frequency 10–80%) and in approximately 30% of the cases with scaphoid waist fracture,2 but only around one-fifth of them are total injuries. A complete tear of the dorsal SL interosseus ligament with an additional tear of one or more secondary stabilizers—radioscaphocapitate (RSC), long and short radiolunate (LRL, SRL), scaphotrapeziotrapezoid (STT) ligamentous complex, or the dorsal intercarpal (DIC) ligament—will allow the scaphoid to rotate into flexion, causing Dorsal intercalated segment instability (DISI) (▶ Fig. 17.2) and eventually scapholunate advanced collapse (SLAC)-wrist (▶ Table 17.1 and ▶ Fig. 17.3). Fig. 17.2 Dorsal intercalated segment instability with an scapholunate angle of approximately 90°. Fig. 17.3 Scapholunate advanced collapse stage III. Stage Arthritic change SLAC I Arthritic changes and osteophyte formation at the radial styloid SLAC II Arthritis at the radioscaphoid joint SLAC III Arthritic involvement of the midcarpal joint (capitolunate and scaphocapitate joints) SLAC IV Arthritis involving all but the radiolunate joint Note that the radiolunate joint is usually not involved. (Reprinted from Watson HK, Ballet FL. The SLAC wrist: scapholunate advanced collapse pattern of degenerative arthritis. J Hand Surg Am 1984;9:358‐365. With permission from Elsevier.) A number of factors may explain the diversity of ligament injury and the progress to SLAC wrist, such as wrist position at the moment of impact; direction, velocity, and point of application of the damaging force; integrity of the secondary ligament stabilizers; and healing capacity and muscle status at the moment of the accident. The only true dynamic stabilizer of the scaphoid is the flexor carpi radialis (FCR), which imparts a supination effect to the scaphoid and at the same time pronates the triquetrum, which together lead to a dorsal co-aptation of the SL joint. A recent retrospective study of over 50 wrists with complete SLL tears and instability showed a lower incidence of DISI deformity in patients with a type II lunate. This finding indicates that the individual wrist constitution also could play a role. The dorsal SLL may disrupt in many different ways and each type of injury requires specific fixation. A recent study has shown—both arthroscopically and in open surgery—that there are four different types of total SL injury (▶ Table 17.2 and ▶ Fig. 17.4).3 Type 1 (lateral avulsion from the scaphoid) is the most common type of injury (42%). Together with type 2 (medial avulsion from the lunate, 16%), the avulsion types of injury represent almost 60%, and those injuries will require open ligament reattachment with transosseous sutures or bone anchors if found in the acute phase, and ligament reconstruction if found later on, but still with a reducibility of the carpal malalignment. Type of SL ligament injury Frequency Type 1: Lateral avulsion off the scaphoid 42% Type 2: Medial avulsion off the lunate 16% Type 3: Mid-substance rupture 20% Type 4: Total elongation 22% Note that in approximately 60% of the injuries the ligament has avulsed off the bone, leaving no ligament remnant on one side. Most patients will therefore require ligament reattachment techniques using transosseous sutures or bone anchors, and arthroscopically assisted SL capsuloplasty is not possible at least in those cases. Abbreviation: SL, scapholunate ligament. Type 3 (mid-substance rupture, 20%) and type 4 (partial rupture plus elongation, 22%) can perhaps be treated early in some cases arthroscopically. Fig. 17.4 There are four distinct types of scapholunate injury according to the Andersson–Garcia-Elias classification. (Courtesy of Andersson and Garcia-Elias.3) S = scaphoid, L = lunate. (Illustration: Dr. Per Fredrikson.) Thus it appears that there are many factors to be taken into account concerning the time to SLAC development, the prognosis, the healing capacity, and the treatment of choice. These factors are the status of the secondary stabilizers; the initial step between the scaphoid and the lunate; the dynamic strength of the patient; the amount of initial trauma; the constitutional wrist morphology; and the type of SL injury (see Box ▶ Factors contributing to the choice of treatment and prognosis for SL ligament rupture and dissociation and ▶ Fig. 17.5). The time to diagnosis is, though, probably the most important factor governing outcome. Fig. 17.5 Total scapholunate ligament injury type 1, with an avulsion from the scaphoid and a significant initial step between the scaphoid and lunate, seen arthroscopically from the 3–4 portal. Here it is easy to believe in a rather rapid scapholunate advanced collapse development. Factors contributing to the choice of treatment and prognosis for SL ligament rupture and dissociation Time from trauma Type of SL injury according to the new Andersson–Garcia-Elias classification Degree of injury (partial/total: Geissler classification) and degree of instability (predynamic, dynamic, or static) Reducibility Healing potential Cartilage status Patient factors and demands Age Health status Professional, vocational, and recreation-related demands Surgeon’s experience, skill, and preferences The initial diagnosis can be difficult as it often takes 3 to 12 months before a dynamic instability will be seen on radiographs (with clenched-fist films) with an SL gap >3 mm and an SL angle >60°. Approximately 5% of “wrist sprains” have an SL tear and the recommendation in all patients with a significant wrist trauma and negative radiographs should be that those patients should be casted and followed up if there are persistent symptoms after 2 weeks. They should be reviewed with a repeated wrist examination including the Watson test (scaphoid shift maneuver), finger extension test, and palpation. The Watson test is supposed to be positive in total SL ligament injuries, although some studies have shown positive Watson tests in about 20% of the normal population, which contributes to the difficulty in diagnosing SL injuries. When performing the scaphoid shift maneuver, the examiner must grasp the wrist from the radial side, placing the thumb on the palmar prominence of the scaphoid while wrapping the fingers around the distal radius. This enables the examiner’s thumb to push on the scaphoid with counterpressure provided by the fingers. The examiner’s other hand grasps the patient’s hand at the metacarpal level to control wrist position. Starting in ulnar deviation and slight extension, the wrist is moved radially with a simultaneous slight flexion and with a constant thumb pressure applied on the scaphoid (▶ Fig. 17.6). The Watson test is positive if the scaphoid is unstable and can be subluxated dorsally and the patient experiences pain at the dorsum of the wrist. Fig. 17.6 Watson test—scaphoid shift maneuver. Patients with initial significant wrist trauma and suspected SL injury should also be examined with radiological stress views with clenched fist in supination and maximal ulnar deviation (▶ Fig. 17.7). A request for MRI should be considered, although MRI is still not always sufficiently sensitive and specific. Arthroscopy is still the gold standard in diagnosing wrist ligament injuries. Early diagnosis is best secured by awareness, attention, and suspicion. Fig. 17.7 Radiological stress view with clenched fist as here, or ulnar deviation, reveals dynamic scapholunate instability. Scapholunate instability and dissociation appear in clinically different grades. Predynamic, occult scapholunate dissociation (SLD) represents an incomplete SLL injury, with a normal radiograph including during stress views. Disruption of the palmar and proximal connection of the SL joint without injury to the most important dorsal ligament is the most common scenario. Dynamic SLD is the result of a complete disruption of all parts of the SLL including the dorsal portion but with intact secondary stabilizers. Carpal malalignment with SL gap > 3 mm and DISI only under stress views are typical findings. In static reducible SLD, the secondary stabilizers have failed and a permanent static carpal malalignment occurs. The carpal subluxation is still reducible and there are no degenerative cartilage changes. Chronic ruptures with time result in fibrosis formation around the scaphoid, carpal collapse, and deformed articular surfaces in the subluxated joints. This pathology leads to a static irreducible SLD, still without substantial cartilage degeneration. The end result of long-standing SLD is always the so-called SLAC wrist (▶ Fig. 17.3). SLAC is the most common pattern of degenerative arthritis of the wrist (▶ Table 17.1).4 It develops following a scapholunate dissociation with rotary subluxation of the scaphoid. The degenerative changes first affect the radial styloid, then the radioscaphoid joint, followed by the midcarpal joints (capitolunate and scaphotrapeziotrapezoidal joints). The head of the capitate in particular can erode quite rapidly when it comes into the gap between the lunate and the scaphoid. The radiolunate joint is typically not involved in the SLAC arthritis because of the spherical shape of the lunate and the congruity of the joint between the lunate and the lunate fossa of the radius. The average time from initial trauma to SLAC development is unknown but is likely to vary, depending on the amount of trauma, injured associated ligaments and secondary stabilizers, initial step between the scaphoid and the lunate (▶ Fig. 17.5), and the individual configuration of the wrist. In practice most often SLAC wrist is found after 3 to 15 years. Partial injuries are not best treated by open surgery. Treatment options are instead arthroscopic debridement or thermal shrinkage, pinning, or physiotherapy with re-education of the FCR. Acute total injuries are preferably treated within 4 to 6 weeks. Chronic SL instability is very difficult to treat because of its complexity and many different methods have been suggested in the past. It is clinically hard to treat SLL ruptures and the results are inconsistent.5,6

17.2 Classification and Prognostic Factors

17.3 Dynamic and Static Scapholunate Instability

17.4 Scapholunate Advanced Collapse: SLAC Wrist

17.5 Open Treatment of Acute and Subacute Scapholunate Ligament Injury and Dissociation

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree