Open Reduction and Internal Fixation of the Symphysis

Michael S. H. Kain

Paul Tornetta III

DEFINITION

The pubic symphysis comprises a fibrocartilaginous disc between the bodies of the two pubic bones.

A diastasis of the pubic symphysis indicates a disruption of the pelvic ring and an unstable pelvis.

The symphysis is disrupted in anterior-posterior compression

(APC) injuries as classified by Young and Burgess and occasionally in lateral compression fractures.

ANATOMY

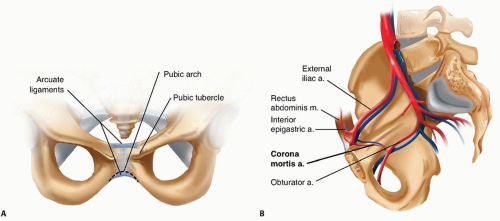

The symphysis is an amphiarthrodial joint, consisting of a fibrocartilaginous disc, and stabilized by the superior and inferior arcuate ligaments (FIG 1A).

The corona mortis is a vessel that represents the anastomosis between the obturator artery and the external iliac artery. It is located about 6 cm laterally on either side of the symphysis (FIG 1B).15

Lateral to the symphysis on the superior rami is the pubic tubercle, a prominence representing the attachment of the inguinal ligament.

This bony landmark must be accounted for when contouring a plate that is going to span the symphysis.

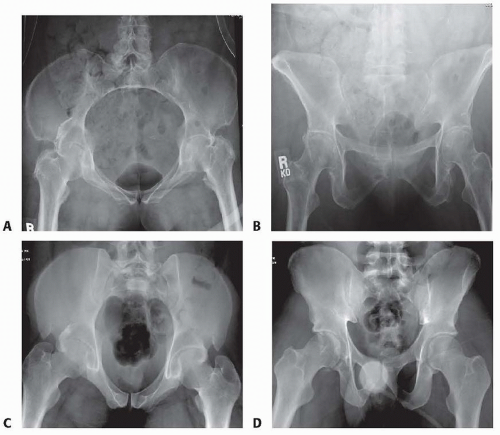

Anatomic variation exists between the sexes, with females having a wider and more rounded pelvis, making their anterior pelvic ring more concave than males (FIG 2).

The pelvic arch formed by the convergence of the inferior rami tends to be more rounded in females because their pubic bodies are shallower than males.

The arcuate ligaments are the main soft tissue stabilizers of the anterior pelvis.

These ligaments arc both superiorly and inferiorly and are firmly attached to the pubic rami.

The sacrospinous and sacrotuberous ligaments play an important role in the stability of pelvic fractures. These ligaments connect the sacrum to the ilium via the ischial spine and the ischial tuberosity. The sacrospinous ligament resists the rotational forces of the hemipelvis, and the sacrotu berous ligament prevents rotation as well as translation of the hemipelvis.13

PATHOGENESIS

The Young and Burgess classification describes the injury by the type of force acting on the pelvis. Symphyseal diastasis is most commonly seen in APC injuries or open book pelvis injuries.

In APC injuries, minor widening of the symphysis may not involve disruption of the pelvic floor, including the sacrospinous ligaments.

In cadaver pelvis, where the symphysis and sacrospinous ligaments were sectioned, more than 2.5 cm of symphyseal widening was observed, thus defining a rotationally unstable pelvis.12

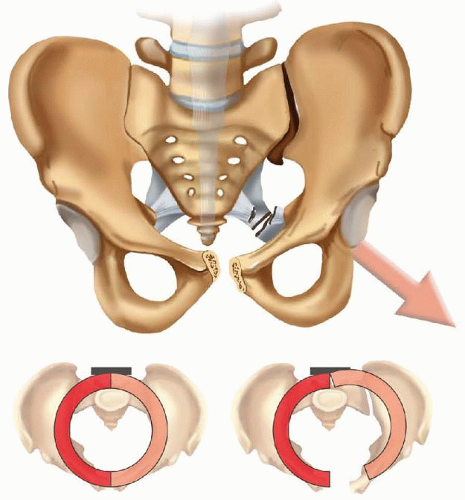

If the pelvic floor and the sacrospinous ligaments are torn, the involved hemipelvis can externally rotate down and

out, rotating on the intact posterior sacroiliac ligaments and creating an unstable pelvis (FIG 3).5

Occasionally, lateral compression injuries involve fractures of the pubic rami and a symphyseal disruption. This occurs when the compressed hemipelvis causes the contralateral rami to fracture and the contralateral symphyseal body to tilt inferiorly. Because one side of the symphysis is off and can compress the bladder or uterus, altering the pelvic ring, it should be reduced to the other pubic body, which remains intact.

These are referred to as tilt fractures, and open reduction and internal fixation should be considered to prevent impingement of the birth canal and bladder.13

A diastasis of the pubic symphysis can also occur in pregnancy and during childbirth because of hormonally induced ligamentous laxity. This can lead to chronic instability, and stabilization of the symphysis has been shown to relieve painful symptoms.16

NATURAL HISTORY

Persistent low back pain; anterior pain; sitting imbalance; and an impaired, painful gait are common sequelae after pelvic fractures.

Early studies looking at pelvic fractures without surgical treatment demonstrated that almost a third of these patients had disabling pain and impaired gait. Only a third had no symptoms if the posterior ring was involved.16

APC type I injuries are Tile type A stable pelvic injuries, which do well with nonoperative treatment. These injuries tend to occur in younger patients involved in motor vehicle trauma or in elderly patients as a result of a direct injury such as a fall.

APC types II and III injuries are unstable injuries. Nonoperative treatment has resulted in late pain in these injuries. In a retrospective study by Tile,13 APC type II injuries treated nonoperatively had a 13% incidence of late pain, with the majority of patients reporting persistent moderate pain. The patients with APC type III injuries reported a 16% incidence of late pain, with most pain being reported as moderate or severe.

Patients with pelvic trauma tend to have other organ systems involved, and these associated injuries contribute to longterm disability. The more severe injuries associated with pelvic fractures are urologic and neurologic injuries.16

Whitbeck et al18 demonstrated higher morbidity and mortality rates as well as an increased incidence of arterial injuries in APC type III injuries compared to other pelvic fractures.

Disruption of the pubic symphysis is associated with urologic injuries. Bladder ruptures and urethral tears occur about 15% of the time in association with pelvic trauma and can lead to late complications such as strictures and incontinence.

These associated injuries potentially lead to a higher infection rate when open reduction and internal fixation is performed.9 An increased incidence of incontinence has also been seen in women with APC injuries.

Neurologic injuries associated with pelvic fractures occur when there is posterior pathology and are more common with sacral fractures and vertically unstable fracture patterns.

Dyspareunia and sexual dysfunction are also described as complications after pelvic fractures.8 They can occur directly from the injury or as a result of ectopic bone formation during healing.

Symphyseal pelvic dysfunction, a relatively common condition, presents as anterior pelvic pain secondary to the laxity in the symphysis. This condition typically resolves spontaneously and can take some time but needs to be differentiated from traumatic symphyseal diastasis as a result of childbirth.

Traumatic diastasis occurs in about 1 in 2000 births to 1 in

30,000 births, and the diastases from pregnancy can be as great as 12 cm.3

Most patients with postpartum displacement recover with no residual pain or instability after treatment with pelvic binders, girdles, and the recommendation to lie in the lateral decubitus position.

There are a limited number of studies looking at symphyseal disruption secondary to pregnancy. The exact incidence of persistent long-term pain is unknown, but chronic pelvic instability can occur if it is unrecognized.11

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

Pelvic injuries usually occur as a result of any high-energy trauma, such as high-speed motor vehicle accidents, motorcycle accidents, or falls from heights.

Patients with pelvic fractures may become hemodynamically unstable, and close monitoring of blood pressure and fluid requirements is needed.

Typically, if a patient requires more than 4 units of blood to maintain hemodynamic stability, an angiogram should be obtained to diagnose and embolize any arterial injuries. Clotting factors and platelets should also be administered.

Patients may have tenderness to palpation in the area of the symphysis. If motion of the pelvis is detected, manipulation of the pelvis should cease, as unnecessary manipulation may disturb any clot formation (see Exam Table for Pelvis and

Lower Extremity Trauma, pages 1 and 2).

If there is no radiographic demonstration of displacement, the iliac wings can be compressed to test for stability of the pelvic ring and each hemipelvis.

A careful examination of the skin to identify areas of ecchymosis and hematoma formation, particularly in the flanks, groin, and abdominal regions, also needs to be performed.

The presence of a Morel-Lavallée lesion indicates that high-energy trauma has occurred in the pelvic region (FIG 4). Recognition of this lesion is important to prevent infection and may need to surgically decompressed, prior to proceeding with definitive fixation of the symphysis.

A good pelvic examination and evaluation of the perineum are essential. Swelling or open wounds in the perineal area may indicate a high-energy mechanism of injury. Open injuries require emergent management.

Evaluation of other organ systems, looking for associated injuries, is essential.

In males, a high-riding prostate on the rectal examination or blood at the meatus may indicate injury to the urethra or bladder, and placement of a Foley catheter should be delayed until a retrograde urethrogram is performed, unless the patient is in extremis.

Urethral injuries are less common in females because the urethra is shorter.

A thorough neurologic examination of the lower extremities also needs to be performed as injuries to the L4 and L5 nerve roots can occur in pelvic fractures. It is essential to test the sensation and motor functions of specific roots, identifying any neurologic injury that can differentiate between a nerve root lesion or a more central lesion.

A limb length discrepancy or a rotational deformity of the lower extremities should prompt radiographic evaluation of the pelvis.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

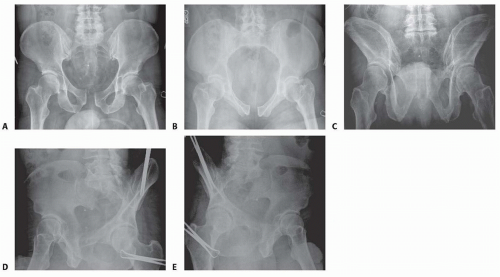

Radiographic evaluation of the pelvis consists of anteroposterior (AP), inlet, outlet, and Judet views (FIG 5).

A retrograde urethrogram and sometimes a computed tomography (CT) cystogram should be performed to rule out an injury to the genitourinary system in men. A CT cystogram is sufficient for females.

A CT scan of the pelvis is also indicated to help evaluate intra-articular injuries to the sacroiliac joints and further delineate the fracture pattern.

A CT angiogram can also be used at the time of the trauma scan to help predict if an arterial bleed is present and requires further treatment with angiography and embolization.10

Angiography may be used to treat patients who are hemodynamically unstable and do not respond to standard resuscitation, particularly if a CT angiogram indicates arterial bleeding.

A stress examination in the operating room can be performed under fluoroscopy to assess stability if there is a question of an unstable pelvis.

Single-leg stance (also known as flamingo) views can also be performed if it is not clear whether an injury is unstable. This is a good examination for evaluating patients who may have chronic instability, such as a female patient with ligamentous laxity secondary to pregnancy or unrecognized pelvic injury.11, 15

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree