Open Reduction and Internal Fixation of Clavicle Fractures

Introduction

Clavicle fractures account for 2.6% to 5% of adult fractures

Historically, nonsurgical management was standard, but with improved surgical techniques, growing evidence shows that surgical management may be beneficial in select patients

Classification

Clavicle fractures are classified based on their location and the degree of comminution and angulation

Allman classification system

Proximal (2% to 3%)

Midshaft (70% to 80%, high-energy, younger patient population)

Distal (21%)

Patient Selection

Indications

Open fracture

Floating shoulder

Impending skin necrosis

Associated neurovascular injuries

Multiply injured trauma patients

Improved outcomes associated with shortening greater than 15 to 20 mm, with 100% displacement, or with comminution

Contraindications

Nondisplaced or minimally displaced fractures in older, sicker patients

Low-demand patient or unfit to undergo surgery

If nonsurgical management pursued, use a sling and course of non–weight bearing

Preoperative Imaging

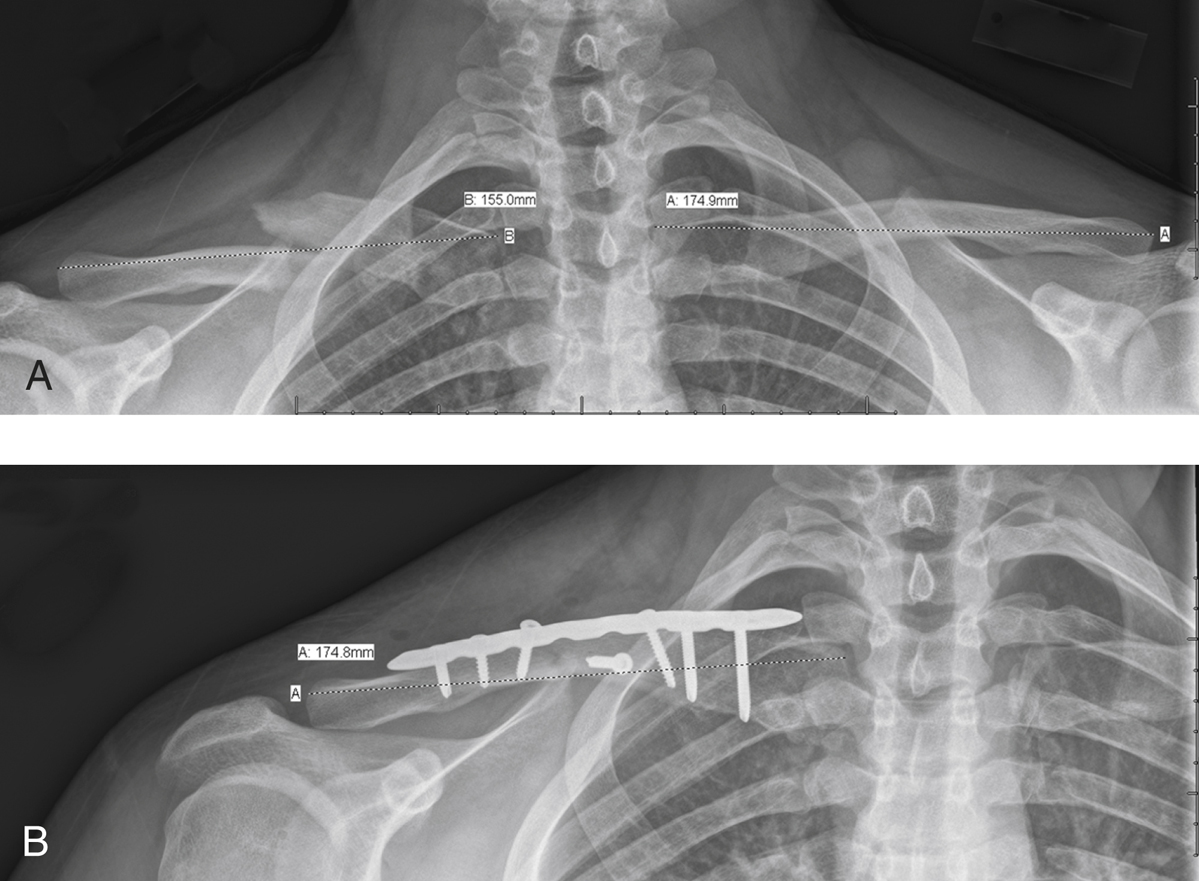

Figure 1AP radiographs of a patient with a right midshaft clavicle fracture. A, Preoperative radiograph demonstrates 2 cm of shortening. B, Postoperative radiograph shows that clavicle length symmetric to the uninjured left side is restored with plate fixation. An interfragmentary screw and a contoured clavicle fracture plate were used.

Orthogonal views of the clavicle

AP chest views (Figure 1) to rule out chest injury (eg, rib fractures, hemothorax, pneumothorax)

Apical oblique view—Shoulder tilted 45° anterior, and radiograph beam 20° cephalad

Abduction lordotic view—X-ray directed 25° cephalad with shoulder abducted above 135°; useful to assess healing postoperatively

Preoperative CT can help to evaluate nonunion and medial fractures extending to the sternoclavicular joint

Procedure for Midshaft Clavicle Fracture

Room Setup/Patient Positioning

Figure 2Photograph shows a patient with a pneumatically controlled arm positioner in place for left shoulder surgery.

Supine or modified beach-chair position on radiolucent table with intraoperative fluoroscopy available

Bump placed at medial portion of scapula

Arm in pneumatic arm positioner (Figure 2)

Palpate and mark the acromion borders, coracoid, triangular soft spot in acromion; acromioclavicular (AC) joint is anterior to soft spot and lateral to coracoid; palpate S-shaped clavicle

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree