Open Reduction and Internal Fixation of Capitellum and Capitellar-Trochlear Shear Fractures

Asif M. Ilyas

Michael Rivlin

Jesse B. Jupiter

DEFINITION

Capitellar fractures are uncommon, accounting for less than 1% of all elbow fractures and 6% of all distal humerus fractures.4

They often are associated with radial head fractures and posterior elbow dislocations.

A classification system for capitellar fractures has been proposed by Bryan and Morrey4 and modified by McKee:

Type 1: complete fractures of the capitellum14

Type 2: superficial subchondral fractures of the capitellar articular surface29

Type 3: comminuted fractures2

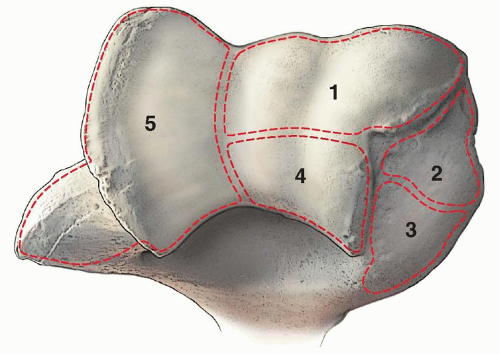

Ring et al25 have proposed a new classification, expanding on the growing understanding that isolated capitellum fractures are rare and often are involved as part of articular shear fractures of the distal humerus. The classification includes five anatomic components, with type 1 articular injuries encompassing the capitellum and capitellar-trochlear shear patterns (FIG 2):

Type 1: capitellum and lateral aspect of the trochlea

Type 2: lateral epicondyle

Type 3: posterior aspect of the lateral column

Type 4: posterior aspect of the trochlea

Type 5: medial epicondyle

More recently, Dubberley and colleagues8 introduced a classification system based on radiographic pattern of injury taking posterior comminution into account.

Type 1: fracture of the capitellum (with or without trochlear ridge involvement)

Type 2: capitellum and trochlea fracture that remain as one fragment

Type 3: capitellum and trochlea as separate fragments

Type A: no posterior condyle comminution

Type B: posterior condyle comminution present

ANATOMY

The two condyles of the distal humerus diverge from the humeral shaft to form the lateral and medial columns, which support the trochlea between them. The anterior aspect of the lateral column is covered with articular cartilage, forming the capitellum. Distally, these two condyles can be visualized as forming a triangle at the end of the humerus.

The capitellum is the first epiphyseal center of the elbow to ossify.

It is covered by articular surface anteriorly but devoid of it posteriorly.

The capitellum is directed distally and anteriorly at an angle of 30 degrees to the long axis of the humerus.

The radial head rotates on the anterior surface of the capitellum in elbow flexion and articulates with its inferior surface in elbow extension.

The lateral collateral ligament inserts next to the lateral margin of the capitellum.

The blood supply of the capitellum is derived posteriorly. It arises from the lateral arcade, which is the anastomosis of the radial collateral arteries of the profunda brachii and the radial recurrent artery.30

PATHOGENESIS

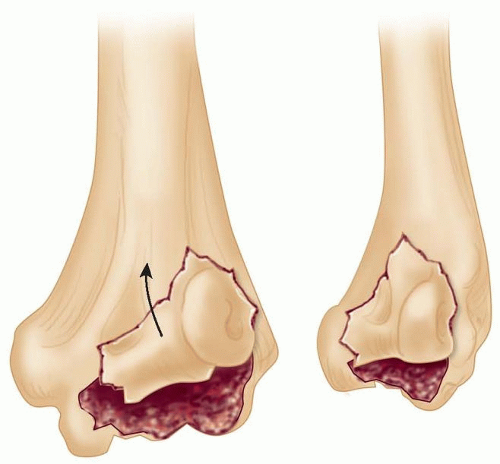

Capitellum and capitellar-trochlear shear fractures involve impaction of the radial head against the lateral column of the distal humerus in a partially extended position, resulting in shearing of the articular cartilage of the distal humerus.

Fracture fragments vary in size and displace superiorly and anteriorly into the radial fossa, resulting in impingement with elbow flexion.

Associated injuries include proximal and distal radial as well as carpal fractures; ligamentous injuries include collateral ligament (lateral more common than medial) and triceps ruptures.8

NATURAL HISTORY

Capitellar fractures occur almost exclusively in adults. These fractures do not occur in children because in that age group, the capitellum is largely cartilaginous, and a similar mechanism of injury would instead cause a supracondylar or lateral condyle fracture.

Capitellar fractures are more common in females, a finding that can be attributed to the increased carrying angle of the female elbow.

Displaced fractures that go untreated can be expected to have a poor outcome owing to the progressive loss of motion from the mechanical block to flexion, potential longitudinal instability of the forearm, and the likely development of subsequent posttraumatic arthrosis from the residual articular incongruity.

FIG 3 • A. Characteristic double arc sign on lateral radiographs of coronal shear fractures. B,C. 3-D CT reconstructions of a coronal shear fracture of the distal humerus.

Capitellar and trochlear fractures are prone to nonunion if multiple articular fragments are present or the posterior column is involved.3

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

Symptoms of capitellar fractures are similar to those of radial head fractures, including pain and swelling along the lateral elbow and pain with elbow motion.

Although there may be variable loss of forearm rotation, loss of flexion and extension is most common, often accompanied by crepitus and pain.

The association of concomitant radial head fractures and ligamentous injuries with capitellar fractures is high.22

The shoulder and wrist should also be examined for concomitant injury.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Standard radiographs are often inadequate for accurate assessment of capitellar fractures.

Lateral radiographs are best for obtaining an initial evaluation of capitellar fractures.

Anteroposterior views do not reliably show the fracture because the outline of the distal humerus is not consistently affected.

The radial head-capitellum view can help identify fractures of the capitellum. This view is a lateral oblique projection taken with the x-ray beam pointing 45 degrees dorsoventrally, thereby eliminating the ulno- and radiohumeral articulation shadows.13

A type 1 fracture appears as a semilunar fragment sitting superiorly with its articular surface pointing up and away from the radial head in most cases.

Type 2 fractures are more difficult to diagnose, depending on the amount of subchondral bone accompanying the articular fragment. They may appear as a loose body lying in the superior part of the joint.

Type 3 fractures display variable amounts of comminution.

Coronal shear fractures show a characteristic “double arc” sign on lateral radiographic views (FIG 3A).

Computed tomography (CT) scans can provide excellent characterization of the fracture, and we subsequently recommend routine use of it for preoperative planning.

CT scanning of the elbow should be done at 1- to 2-mm intervals using axial or transverse cuts.

Three-dimensional (3-D) CT reconstructions provide the best detail and ability to appreciate the anatomic orientation of the fracture patterns and should be considered if 3-D imaging is available (FIG 3B,C).

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Radial head fracture

Distal humeral lateral condyle fracture

Elbow dislocation

NONOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

We recommend operative management for capitellum and capitellar-trochlear shear fractures.

Truly nondisplaced and isolated capitellum fractures can be splinted for 3 weeks, followed by protected motion. However, close supervision is required, as this fracture is inherently unstable and prone to displacement.

Closed reduction techniques, which have been described in the literature, should be performed with caution, and only complete anatomic reduction should be accepted for nonoperative management.5, 23

Capitellar-trochlear shear fractures should not be treated nonoperatively because of their inherent instability and the expectant loss of motion and posttraumatic arthrosis from residual articular incongruity.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

The short-term goal of surgery is anatomic reduction and stable fixation of the fracture to allow for early motion without mechanical block.

The long-term goals of surgery are a pain-free elbow with maximal motion, minimal stiffness, and avoidance of posttraumatic arthrosis.

Capitellar fractures are uncommon, and the wide array of treatment options presented in the literature is based on relatively small series.

Treatment options include closed reduction,5, 23 open excision,1, 10, 20 open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF), and arthroplasty.6, 11

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree